Study on Synthesis Method of Ginsenoside

Ginsenosides are the main active ingredients of precious medicinal herbs such as ginseng and American ginseng. Modern pharmacological studies have shown that ginsenosides have good pharmacological activities such as anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidation and inhibition of apoptosis [1]. Ginsenosides belong to the triterpenoid class and are glycoside compounds formed by the connection of a glycoside precursor and a sugar. According to the aglycone, ginsenosides can be divided into three types: one is the oleanane-type pentacyclic triterpene saponin Ro, whose aglycone is oleanolic acid; the other two are ginsenosides of the ginsenol type (such as Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, F2, Rg3, Rh2, etc.) and ginsenosides of the triterpene type (e.g. Re, Rg1, Rg2, Rf, Rh1, etc.). Both types belong to the dammarane-type tetracyclic triterpene saponins and account for the majority of ginsenosides, making them the main active ingredients. So far, more than 60 ginsenosides have been isolated and their structures determined. Most of the ginsenoside monomers have significant pharmacological effects and show good prospects for new drug development. For example, Rg1 and Rb1 have anti-aging activity, and Rg3 and Rh2 have anti-tumor activity [2].

The content of ginsenosides in ginseng and American ginseng is relatively low. Limited natural resources can hardly meet the ever-increasing demand for medicine and research and development. Moreover, long-term dependence on wild resources as a source of medicine will inevitably lead to the depletion of natural resources and seriously damage the ecological balance. The artificial cultivation of ginseng and American ginseng requires a 4-15 year growth and cultivation cycle, and faces problems such as pesticide residues, heavy metal pollution and species degradation. These are all constraints on large-scale cultivation. In order to get rid of the dilemma of scarce medicinal resources and at the same time protect precious natural resources, in recent years, domestic and foreign scholars have explored the biosynthesis of ginsenosides through tissue culture, biotransformation and synthetic biology, and have achieved some results. This paper reviews these developments and looks ahead to the prospects for the biosynthesis of ginsenosides.

1 Research using tissue culture to solve the shortage of ginseng resources

Since the mid-20th century, many researchers have been devoted to the study of tissue culture of ginseng and American ginseng, attempting to solve the problem of resource supply of these precious medicinal materials through tissue and cell culture, or to make rapid propagation possible through the obtainment of test tube seedlings. Regarding the study of tissue culture of ginseng and American ginseng, there have been many review articles in recent years [3, 4]. Plant tissue and cell culture must ultimately establish large-scale culture methods – reactor culture – in order to achieve industrial production. Japan has successfully carried out ginseng cell culture on a 20 000 L bioreactor at a rate of 100 kg per month for the production of food additives, and the composition of the ginsenosides in the culture is almost exactly the same as that of cultivated ginseng roots [5]. South Korea has also made great progress in the fermentation culture of ginseng adventitious roots and fibrous roots, and the scale of the reactor has reached 10,000 L [6]. China has developed the Ding Jiayi series of cosmetics through ginseng callus culture [7].

Although the tissue and cell culture research of ginseng and American ginseng has been relatively in-depth, and some progress has been made in cell culture, fibrous root and crown gall tumor culture, and reactor culture, However, there are still some problems, such as unstable cell lines, difficulties in scale-up culture, low content of the target product, and high costs due to complex culture conditions. Therefore, it is necessary to find more suitable culture conditions and technical methods that are easy to industrialize in order to meet people's pharmaceutical and research and development needs for ginseng and American ginseng medicinal materials and ginsenosides.

2 Research on obtaining rare ginsenosides and aglycones through biotransformation

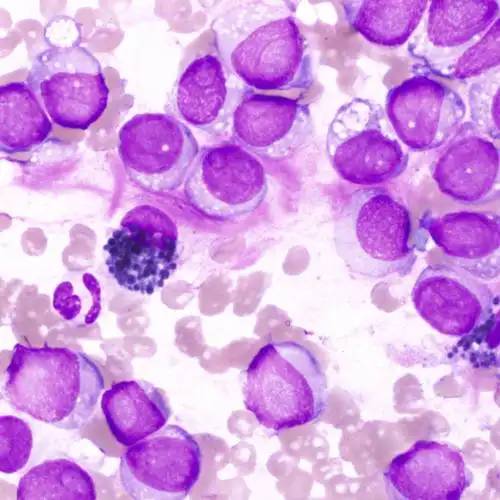

Various ginsenosides are present in different amounts in Panax plants and have different pharmacological functions. Some ginsenosides, such as Rb1 and Rg1, are highly abundant, while others, such as Rh1, Rh2, Rh3 and Rg3, are rare ginsenosides that are present in very small amounts [2]. Many pharmacological studies have shown that rare ginsenosides generally have better pharmacological activity. The ginsenoside protopanaxadiol has the strongest anti-tumor activity, and as the number of sugar bases increases, the anti-tumor activity of ginsenosides decreases in turn, that is, protopanaxadiol > monosaccharide glycosides > disaccharide glycosides > trisaccharide glycosides > tetrasaccharide glycosides [8]. By studying the metabolic patterns of ginsenosides in the body, it was also found that most ginsenosides are poorly absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, and that the secondary ginsenosides and ginsenosides that have been deglycosylated have stronger pharmacological activity and higher bioavailability than ginsenosides [9-11].

Rare ginsenosides and aglycones are present in very small amounts in the raw ginseng plant, cell cultures, adventitious roots and fibrous roots. In the past, they were mainly obtained by physically and chemically hydrolyzing the glycosidic bonds of ginsenosides, but the hydrolysis conditions were harsh, not easy to control, and produced many reaction by-products. In addition, a large amount of pollutants such as organic solvents, acids and alkalis were emitted, causing great harm to the environment. In order to avoid damaging the ecological environment and to obtain resources for sustainable use, many researchers have used biotransformation pathways to modify the sugar chain structure of ginsenosides in order to obtain rare ginsenosides and aglycones [12].

Bioconversion is a process that uses an organism (cells, organelles) or an enzyme as a catalyst to achieve chemical conversion. It is a chemical reaction in which a biological system (including bacteria, fungi, plant tissues, etc.) modifies the structure of an exogenous substrate. Its essence is the catalytic reaction of an exogenous substrate using an enzyme produced by the organism itself. Biological transformation has the advantages of being highly selective, using mild reaction conditions, producing few by-products, being easy to process and environmentally friendly. In recent years, there has been an increasing amount of research on the biotransformation of ginsenosides, with many meaningful results. The biotransformation of ginsenosides mainly involves the use of microorganisms or enzymes to modify the glycosyl structures at the C3 and C20 positions of ginsenol-type ginsenosides and at the C6 and C20 positions of triol-type ginsenosides, so that the higher content of ginsenosides can be hydrolyzed and directed converted into rare ginsenosides and aglycones [13]. The main methods of biotransformation are microbial transformation and enzymatic transformation.

2.1 Microbial transformation

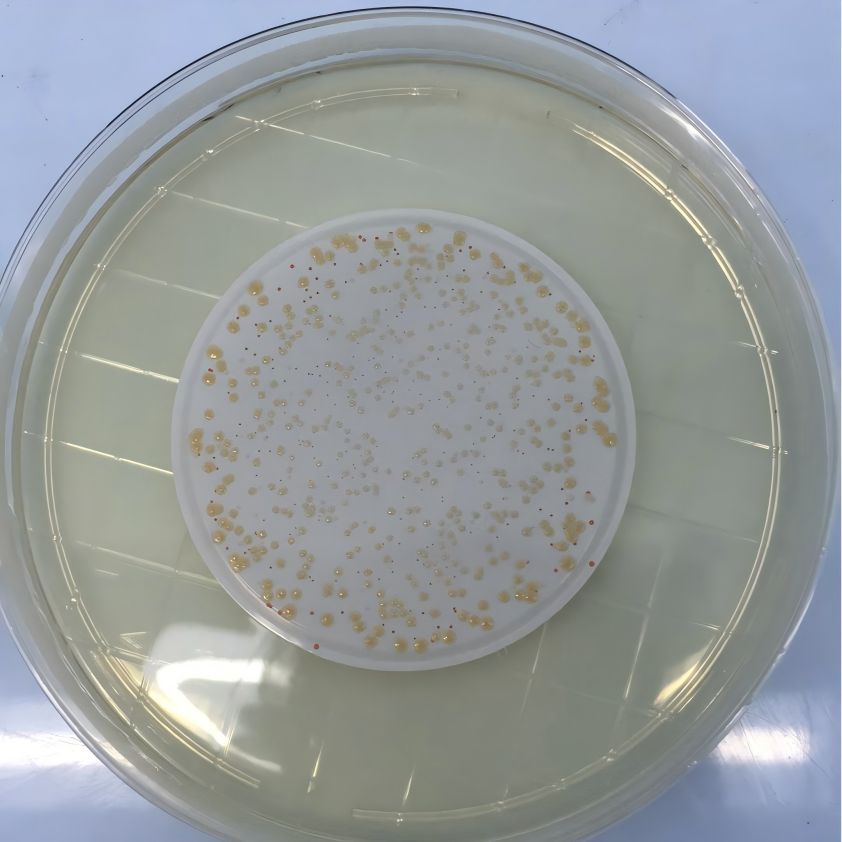

The microbial transformation method is low-cost, has few by-products, and is widely used. Many researchers have simulated the in vivo metabolism of ginsenosides and found that the real active ingredient that exerts the effect of ginsenosides is the aglycone by converting ginsenosides through some intestinal flora, which lays the foundation for the development of new drugs [14]. Bae et al. [15] isolated lactic acid bacteria from intestinal flora that can convert ginsenosides into Compound K, and the conversion of Rg3 to Rh2 and PPD by the intestinal bacteria Bacteroides sp., Eubacterium sp. and Bifidobacterium sp. [16]. In addition to intestinal bacteria, the microorganisms that biotransform ginsenosides also include fungi such as Aspergillus, Penicillium, Rhizopus, and Mucor species. Dong et al. [18] found that the small filamentous fungi Aspergillus niger (3.1858) and Absidia coerulea (3.3538) had the ability to convert Rg1 to Rh1, with a conversion rate of 80.9%.

Fu Jianguo [19] used a large medicinal-food dual-purpose fungus to co-culture with American ginseng and its root extract, and biotransformed ginsenosides using solid-state fermentation. The results showed that the enzyme system secreted by the mycelium has the function of decomposing diol-type saponins, and has a very weak decomposition function for triterpene saponins, which can produce Compound K. Cheng et al. [20] used Caulobacter leidyia, which produces β-glucosidase, to convert ginsenoside Rb1 to F2. Bao Haiying et al. [21] used Rhizopus sp. to convert ginsenoside Re to Rg1, Rg5 and Rk1, with a conversion rate of up to 92.16%. Cui Yu et al. [22] isolated four strains from the soil where ginseng was cultivated. By converting ginseng fruit total saponin (SFPG), a strain of Fusarium spp. that can convert Compound K was screened out. This strain has high specificity and high conversion efficiency, providing a new way for the industrial production of Compound K.

Dai Jun-gui et al. [23, 24] have also done a lot of work on the biotransformation of ginsenosides. Rg1 and Rb1 were converted by Fusarium oxysporum Z-001, and a total of 9 metabolites were obtained, of which 6α, 12β- dihydroxydammar-3-one-20(S)-O-β-D-glucopyranoside and 3a-oxa-3a-homo-6α, 12β-dihydroxydammar-3-one-20(S)-O-β-D-glucopyranoside are new compounds; Rg1 was converted into five metabolites by the blue-colored Aspergillus sp. AS3.2462, of which 3-oxo-7β-hydroxy-20(S)-protopanaxatriol and 3-oxo-7β, 15α-dihydroxy-20(S)-protopanaxatriol are new compounds.

2.2 Enzyme conversion

Compared with microbial transformation, the enzyme transformation method has a short reaction cycle, less pollution, high purity of the product obtained, strong controllability, and a certain degree of specificity. Enzymes of different properties act on glycosidic bonds of different conformations and compositions, thereby allowing the targeted formation of the desired product. Ko et al. [25] studied the hydrolysis of a mixture of triterpene glycosides by various glycoside hydrolases. The mixture of triterpene saponins was hydrolyzed using crude enzyme solutions of galactosidase from Aspergillus oryzae and lactase from Penicillium sp. respectively, produced a large amount of Rg2 and Rh1; the hydrolysis of the triol-type saponin mixture using crude enzyme extract of naringinase derived from Penicillium decumbens produced the intestinal metabolite F1 and a small amount of 20(S)-PPT. This is the first report of the efficient preparation of Rg2, Rh1 and F1 using enzymatic hydrolysis of the triol-type saponin mixture. Subsequent studies on the conversion of the diol glycoside mixture by various glycosidase enzymes found that crude enzyme solutions of lactase from Aspergillus oryzae, β-galactosidase and cellulase from Trichoderma viride could convert F2, Compound K and Rd, respectively; A crude enzyme solution of lactase from Penicillium can convert Rd, Rg3 and Compound K. This is the first report of the enzymatic preparation of F2 and Rg3 in large quantities using a mixture of diol-type saponins [26].

Liu et al. [27] used crude glycosidase obtained from Aspergillus niger to convert Rg3 (R) to PPD (S, R), with a conversion rate of up to 100%; and converted Rf to 20(S)-PPT with a conversion rate of 90.4% [28]. The research group of Jin Fengxie [29] has carried out a lot of work on the production of the rare saponin Rh2 by enzymatic conversion. Using the newly discovered ginsenoside β-glucosidase, the glycosyl group of ginsenoside diol type was partially hydrolyzed to produce Rh2 and other saponins. They screened and bred enzyme-producing engineered bacteria, developed a separation and purification technology for the secondary saponins of enzymatic conversion products, Rh2 can be produced industrially through enzymatic conversion. This method has been shown in production practice to have a conversion rate of more than 60% for the production of Rh2 from ginsenoside diol, a purity of Rh2 of 90%, and a yield of Rh2 of more than 0.5% of the raw ginseng material, which is 500 times higher than the yield from red ginseng. The recovery rate of the enzyme after the reaction is 60%.

With the development of genetic engineering technology, in recent years some researchers have begun to attempt to transfer glycosidase genes into E. coli. Some progress has been made in the biotransformation of ginsenosides by the recombinant enzymes obtained through high expression. Noh et al. [30] transferred the β-glycosidase gene cloned from Sulfolobus solfataricus into E. coli. The recombinant enzyme obtained was able to convert ginseng root extract into Compound K, with a conversion rate of 80.5%. Yoo et al. [31] transferred the β-glycosidase gene cloned from Pyrococcus furiosus into E. coli, and the resulting recombinant enzyme first converted ginseng root extract into Compound K, with a conversion rate of 79.5%, and then into the aglycone PPD, with a conversion rate of 100%, The yield of ginsenosides can reach 1.8 g·L-1. The yields of Compound K and ginsenosides in this study are the highest reported in the literature, so it has good prospects for industrialization.

Although considerable progress has been made in the biotransformation of ginsenosides, in order to achieve industrialization, it is necessary to screen for high-yielding strains and enzymes that can specifically transform, or obtain recombinant enzymes with high transformation activity through genetic engineering, and then establish suitable industrial production conditions. This is of great significance for the large-scale production of ginsenoside derivatives and the research of innovative drugs.

3 Exploration of Synthetic Biology Research on Ginsenosides

Synthetic biology of natural medicines is based on genomic research, which involves discovering and characterizing the components involved in the biosynthesis of natural medicines, designing and standardizing them using engineering principles, and reconstructing biosynthesis pathways and metabolic networks by assembling and integrating them in chassis cells, so as to achieve the targeted and efficient heterologous synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients and solve a series of major problems in the research, development and manufacturing of natural medicines [32]. In the field of natural drug design and synthesis, the application of synthetic biology enables more precise control of metabolic pathways. Genetic manipulation of natural product biosynthesis pathways can be used to produce innovative natural product-based drug molecules. Synthetic “super-producers” that can produce important natural drugs can also be designed and constructed. The desired target compounds can be directly obtained simply by fermenting the “super-producers”. and is expected to become one of the most promising green technologies for drug production in the future. It can effectively solve the resource problems that may be caused by the research and development of natural drugs from plants. At present, synthetic biology has made great progress in the manufacture of some medicinal natural products.

Wang Wei et al. [33] cloned the taxane synthase gene from Chinese yew for the first time, and constructed a taxane biosynthesis pathway by introducing it into Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The recombinant bacteria can directly produce taxane, the precursor of paclitaxel, laying the foundation for the synthetic biology research of taxane compounds. Ajikumar et al. [34] used Escherichia coli to achieve the fermentation production of paclitaxel's key precursor, taxol. The yield can reach 1 g·L-1 through fed-batch cultivation, which means that it is hoped that by further optimizing other steps of paclitaxel biosynthesis, the large-scale preparation of paclitaxel through synthetic biology will eventually be achieved.

Kong Jianqiang et al. [35] obtained the artemisinin precursors zhishuihuai-4, 11-diene and artemisinic acid by transferring the genes related to artemisinin biosynthesis to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Moreover, the zhishuihuai-4, 11-diene synthase was fully genetically optimized, which significantly improved the catalytic efficiency of zhishuihuai-4, 11-diene synthase and which greatly improves the yield of artemisinin-4, 11-diene in the engineered bacteria. Westfall et al. [36] constructed a Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered strain for the production of artemisinin-4, 11-diene, which can reach a yield of 40 g·L-1 through batch fed-batch culture, and synthesize it into dihydroartemisinic acid, a direct precursor of artemisinin, with a total yield of 48.4%. This makes it possible to prepare artemisinin precursors in large quantities through synthetic biology, which will simplify the synthesis route of artemisinin and thus greatly reduce the production cost of artemisinin.

In recent years, research on the biosynthesis pathway of ginsenosides and its reaction mechanism has made some progress, laying the foundation for the production of ginsenosides through synthetic biology technology [37, 38]. The ginsenoside biosynthesis pathway includes more than 20 consecutive enzymatic reactions (Figure 1). The key enzymes are 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR), farnesyl diophosphate synthase (FPS), squalene synthase (SS), squalene epoxidase (SE), and dammarenediol-II synthase (DDS). FPS), squalene synthase (SS), squalene epoxidase (SE), dammarenediol-II synthase (DS), AS), cytochrome P450 (CYP450) and glycosyltransferase (GT), etc.

3.1 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme

A reductase (HMGR) HMGR is recognized as the first rate-limiting enzyme in the ginsenoside biosynthesis pathway. It is the key enzyme that first functions in the terpenoid synthesis process, influencing the biosynthesis of ginsenosides by affecting the production of IPP and DMAPP, the precursors of ginsenosides. Wu et al. [39] cloned the HMGR gene from 4-year-old American ginseng roots. The encoded protein consists of 589 amino acids. Bioinformatics analysis showed that HMGR contains two transmembrane domains and a catalytic domain. This gene has high homology with HMGR genes cloned from many plants, especially with the HMGR gene of Camellia sinensis, which has a homology of up to 83.8%. The biosynthesis of camptothecin, a monoterpene indole alkaloid in Camellia sinensis, must go through the mevalonate (MVA) pathway. it can be inferred that the HMGR gene is closely related to the biosynthesis of ginsenosides.

3.2 Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FPS)

Kim et al. [40] cloned the gene encoding FPS from ginseng roots, PgFPS, and the encoded amino acid sequence was 77%, 84%, 87%, and 95% homologous to FPS from Arabidopsis, rubber, Artemisia annua and Centella asiatica, respectively. Southern blot analysis showed that there are more than two genes encoding FPS in ginseng. The recombinant protein was confirmed to have the activity of FPS by expressing PgFPS in Escherichia coli. Treatment of ginseng hairy roots with methyl jasmonate was found to increase both the mRNA level of PgFPS and the activity of FPS. Methyl jasmonate has previously been reported to induce ginsenoside accumulation in ginseng root suspension cells [41], which is most likely related to the increased expression of PgFPS.

Kim et al. [42] also overexpressed PgFPS from ginseng in hairy roots of Centella asiatica and found that the mRNA level of the damaran synthase in Centella asiatica was significantly increased, and the production of the triterpene saponins madecassoside and asiaticoside increased transiently. The above studies show that FPS plays an important role in the biosynthesis of triterpenoids and is an important component for improving ginsenoside production using synthetic biology techniques.

3.3 Squalene synthase (SS)

SS is located at a branch point of the isoprenoid pathway and catalyzes the initial step in the synthesis of sterols and triterpenoids. Its content and activity play a very important role in the production of ginsenosides. Lee et al. [43] cloned the SS gene PgSS1 from a cDNA library constructed from ginseng leaves. This gene is 84.1%, 75.78%, 81.45% and 71.33% homologous to the SS genes in soybean, Arabidopsis, tobacco and rice, respectively, with 84.1%, 75.78%, 81.45% and 71.33% homology. A plant expression vector for the SS gene was constructed, and the expression of the gene was up-regulated by transforming ginseng to obtain adventitious roots. The results showed that the expression of all downstream genes was up-regulated, which led to an increase in sterols and ginsenosides, indicating that SS plays a regulatory role in the biosynthesis of both sterols and ginsenosides.

Kim et al. [44] cloned two other PgSS1 homologous genes, PgSS2 and PgSS3, from an expressed sequence tag (EST) library constructed using adventitious roots as the material. Functional complementation analysis showed that PgSS1, PgSS2 and PgSS3 can all restore the ergosterol prototrophic phenotype of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae SS gene defective mutant. In situ hybridization analysis showed that the transcription levels of these three genes in different organs of ginseng were different. These results indicate that the three SS genes have different expression patterns but are all involved in the synthesis of squalene in ginseng. Seo et al. [45] transferred the SS gene of ginseng into the callus of Siberian ginseng by Agrobacterium tumefaciens to express the final metabolites. The results showed that enhancing the activity of ginseng SS significantly increased the production of sterols and also increased the production of triterpenoid saponins. It is therefore inferred that SS is a key enzyme in the synthesis of ginseng saponins. Increasing the expression of SS not only promotes the conversion of FPP to squalene, but also upregulates the activity of other downstream enzymes, thereby increasing the production of sterols and triterpenoids.

Jiang Shicui et al. [46] designed sense and antisense fragment primers based on the ginseng SS gene to construct a SS gene interference expression vector. The vector was transformed into ginseng callus tissue via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. The SS gene expression level in the transformed callus tissue was reduced, and the saponin content also changed. It is inferred that SS is a key enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway of ginsenosides, and that inhibiting the expression of the SS gene can regulate the production of ginsenosides. Therefore, SS is also a very important component for improving the production of ginsenosides using synthetic biology techniques.

3.4 Squalene epoxidase (SE)

SE catalyzes the first oxidative reaction of sterol and triterpenoid biosynthesis and is considered to be one of the rate-limiting enzymes in its synthesis. Han et al. [47] cloned two SE genes, PgSQE1 and PgSQE2, from a cDNA library constructed from ginseng leaves and adventitious roots, respectively. PgSQE1 RNA interference (RNAi) technology was used to find that silencing PgSQE1 in transgenic ginseng roots can significantly upregulate the expression of PgSQE2 and cycloartenol synthase (CAS), resulting in an increase in sterol content. These results indicate that PgSQE1 and PgSQE2 have different regulatory mechanisms, with PgSQE1 only participating in the synthesis of ginsenosides and not involved in sterol production. Jiang Shicui et al. [48] investigated the differences in the total saponin and monomer saponin content in different tissues and organs of American ginseng and the relationship between this and the expression levels of the SS and SE genes. and found that the expression levels of SS and SE genes in 14 tissues and organs were significantly different, and there was a significant positive correlation with the contents of ginsenosides Re, Rg1, Rb1, Rd and total ginsenosides. This shows that SS and SE play an extremely important role in the ginsenoside synthesis pathway.

3.5 Dammarenediol-II synthase (DS) and a-amyrin synthase (AS)

The 2,3-oxidosqualene cyclization catalyzed by oxidosqualene cyclase (OSC) is a key site in the biosynthesis of triterpenoid saponins and sterols. OSC forms a multigene family, and oxidosqualene cyclization can produce more than 100 triterpenoids with different skeletons. OSC genes have been cloned from various plants. Two OSC genes related to ginsenoside synthesis have been cloned from ginseng: the DS and AS genes, which are the key enzyme genes for the synthesis of ginsenosides of the damarane and oleanane types, respectively. Kushiro et al. [49] used ginseng hairy roots as material to prepare microsomes, found that it could cyclize 2, 3-oxo-squalene to dammarane-II in vitro. Tansakul et al. [50] designed degenerate primers based on the conserved sequence of the OSC gene and cloned the DS gene PNA from the ginseng root. After being transferred into Saccharomyces cerevisiae, this gene can catalyze the production of dammarane-II.

Han et al. [51] cloned a DS gene DDS from an EST library constructed using ginseng flowers, which is consistent with the above-mentioned PNA gene sequence. It was found that yeast transformed with the DDS gene can produce damarene-II and hydroxydamarenone; methyl jasmonate can upregulate the expression of the DDS gene; silencing the DDS gene by RNAi technology can reduce the production of ginsenosides in ginseng roots to 84.5% of the original. Lee et al. [52] transferred the DDS gene into tobacco, which produced damarane-type ginsenosides, thereby significantly improving the resistance of tobacco to tobacco mosaic virus. These results show that DS plays a very important role in the biosynthetic pathway of ginsenosides and is an important component for obtaining dammarane-type ginsenosides using synthetic biology techniques. AS catalyzes the cyclization of 2,3-oxidosqualene to form eudesmanolide, and is so far the only key enzyme found in the synthesis of oleanane-type ginsenosides.

Kushiro et al. [53] cloned the cDNA sequence of AS from ginseng hairy roots, and transferred PNY into Saccharomyces cerevisiae to catalyze the production of ginsenoside Rb1. Zhao Shoujing et al. [54] also cloned the AS gene from the ginseng root, and successfully constructed an antisense plant expression vector for the AS gene. By establishing an antisense expression vector for the AS gene and using antisense RNA technology to inhibit the expression of the AS gene, the metabolic flow is mainly directed towards the damarane-type triterpene saponin branch, thereby increasing the content of ginsenosides.

3.6 Cytochrome P450 (CYP450)

CYP450 is a key enzyme in the ginsenoside biosynthesis pathway, as it carries out complex modifications such as hydroxylation and oxidation of the triterpene carbon skeleton of ginsenosides. In recent years, using next-generation sequencing technology and bioinformatics analysis, related CYP450s involved in ginsenoside biosynthesis have been screened, and the biological functions of candidate genes have been verified, further elucidating the ginsenoside biosynthesis pathway [55]. Han et al. [56] performed transcriptome sequencing on methyl jasmonate-induced ginseng adventitious roots, and obtained nine candidate full-length CYP450 genes through splicing, annotation, and amplification. Among them, the CYP716A47 gene not only responded to methyl jasmonate induction by upregulating its expression, but also increased the production of ginsenosides in ginseng roots after being transferred to transgenic ginseng plants overexpressing the SS gene. Transforming the CYP716A47 gene into Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the expressed recombinant protein can catalyze the hydroxylation of the C-12 position of damarenediol-II to convert it into protoginsenol. DS and CYP716A47 were simultaneously transferred into Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and the production of protopanaxadiol was detected in the recombinant strain. This report is the first to functionally confirm the CYP450 involved in ginseng saponin synthesis.

Chen Shilin's [57] research group applied high-throughput 454GS FLX sequencing technology to conduct a transcriptome study of ginseng, American ginseng and Panax notoginseng, and mined CYP450 from a large amount of transcriptome data, providing an important basis for further screening of CYP450 involved in ginsenoside synthesis. Sun et al. [58] performed high-throughput sequencing on American ginseng roots and and obtained 150 CYP450s through splicing and annotation. The transcript levels of 27 CYP450s with the highest expression were selected for methyl jasmonate induction experiments. Among the root, stem, leaf and flower tissues, only the contig00248 transcript showed the same expression pattern as DS. The contig00248 transcript is phylogenetically close to the Arabidopsis CYP88 family. The article uses the contig00248 transcript as a key candidate CYP450 for the oxidation of damascenone-II or protopanaxadiol.

Luo et al. [59] performed high-throughput sequencing on Panax notoginseng roots, which were then assembled, annotated and amplified 15 full-length CYP450s. Among them, the Pn00158 transcript has a high degree of similarity to the American ginseng candidate CYP450 contig00248 transcript, and is homologous to the functionally confirmed ginseng CYP716A47 amino acid sequence with a high degree of homology of 97.95%. which infers that Pn00158 is very likely to be the CYP450 involved in ginsenoside biosynthesis in Panax notoginseng. Han et al. [60] cloned CYP716A53v2 from a methyl jasmonate-induced ginseng adventitious root EST library, and the recombinant protein expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae can catalyze the C-6 hydroxylation of protoginsenolide to convert it into protoginsenolide . The above research progress on ginsenoside-related CYP450 has greatly advanced the study of the ginsenoside biosynthesis pathway and also provided important components for the exploration of ginsenoside production through synthetic biology techniques.

3.7 Glycosyltransferase (GT)

The glycosylation reaction catalyzed by GT is the final step in the biosynthesis of ginsenosides. The main process is the transfer of the active sugar molecule of nucleoside diphosphate to the ginsenoside aglycone substrate to form a glycoside bond. Glycosylation can increase the stability and water solubility of ginsenosides, and this process also determines their diversity. GTs also exist in plants in the form of gene families with a high degree of specificity. Different GTs are required for the transfer of different sugar moieties or to different sugar acceptors. Chen et al. [61] first isolated a GT from ginseng hairy roots, and determined its molecular mass to be 56.6 kD using SDS-PAGE. and its enzymatic characteristics were preliminarily studied. Yue et al. [62] isolated and purified a GT from Panax notoginseng suspension cells, which can convert Rd to Rb-1. However, there has been no report of cloning a GT gene from Panax plants. Glycosylation is the most downstream step in the ginsenoside biosynthesis pathway, and in-depth research is of great significance for selectively obtaining highly valuable ginsenosides.

In summary, significant progress has been made in the study of the basic framework of the ginsenoside biosynthesis pathway and the related enzymes. More than 20 genes encoding enzymes related to ginsenoside biosynthesis have been cloned from ginseng and American ginseng and other plants in the genus Panax and functionally verified, providing the basic biological components for the production of ginsenosides through synthetic biology techniques and laying a good foundation for this research.

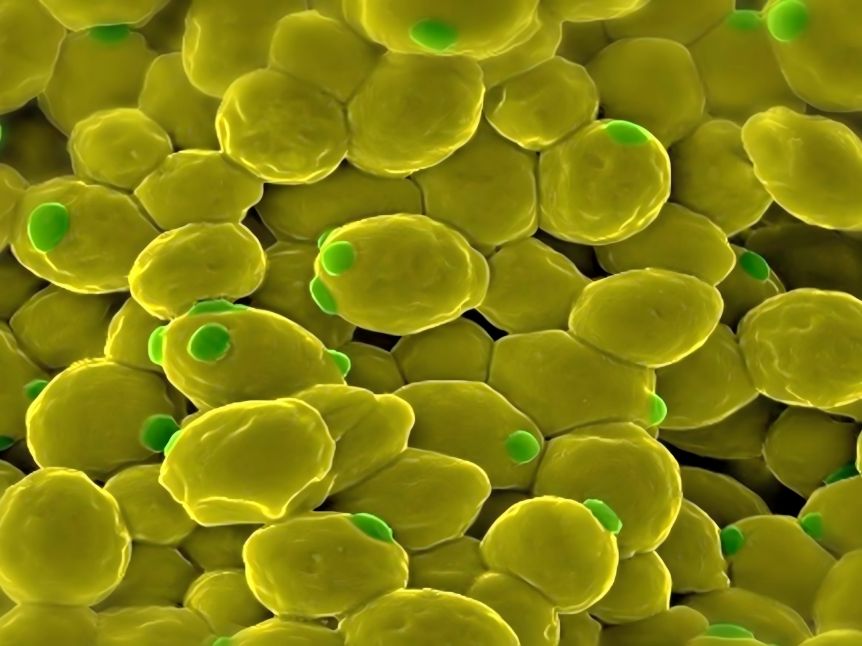

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is generally used as a chassis cell to verify the function of genes encoding key enzymes involved in ginsenoside biosynthesis. This is because Saccharomyces cerevisiae has the characteristics required for an excellent chassis cell, such as the ability to grow in a culture medium with simple nutrients, easy to scale up production using a bioreactor, multiple nutrient-deficient types to choose from, and multiple selectable markers to use. In particular, 2,3-oxidosqualene, which is produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae through its own intrinsic MVA pathway, is the precursor of synthetic ginsenosides. This provides great convenience for the construction of the ginsenoside metabolic pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In addition, since the glycosyl groups of some ginsenosides are not necessary for pharmacological effects, the pharmacological activity of ginsenoside aglycones that have been deglycosylated is even stronger than that of ginsenosides. Therefore, it is also of great significance to directly obtain ginsenoside aglycones through synthetic biology.

4 Conclusion

Ginseng, American ginseng and their saponins have become a research hotspot due to the growing demand for medicine and research and development. Some progress has been made in these areas. In addition to the artificial cultivation of ginseng and American ginseng, several methods for obtaining ginseng saponins have been reported at home and abroad, including tissue culture, biotransformation and synthetic biology techniques. Tissue culture is currently an important way to solve the problem of drug sources. Given that the metabolic pathway of ginsenosides has gradually become clear, the expression of key enzyme genes can be increased through genetic engineering techniques to improve the synthesis of ginsenosides and obtain high-yield cell lines, thereby more effectively alleviating the growing demand for medicine and research and development. Biotransformation has outstanding advantages in obtaining rare ginsenosides and their aglycones, and it may also be possible to obtain ginsenoside derivatives that do not exist in natural plants. Synthetic biology research on ginsenosides is also a promising approach with broad development prospects.

The biosynthesis of ginsenosides is a complex and dynamic process regulated by multiple factors. In order to achieve the goal of producing ginsenosides through synthetic biology, it is necessary not only to transfer the cloned genes of the relevant key enzymes into suitable chassis cells, and artificially modify these genes to enable heterologous and efficient expression, but also to conduct in-depth mining of some regulatory genes that regulate the ginsenoside metabolic network, in order to find the switch that turns on the entire metabolic network, thereby improving the overall expression level of genes in the entire metabolic pathway and more effectively increasing the production of ginsenosides. So far, although there have been some major advances in the synthetic biology research of ginsenosides in terms of obtaining biological components and verifying their functions, research on the modification of chassis cells and the assembly of metabolic pathways has only just begun. Therefore, related disciplines should join forces to jointly promote the development of this research.

References

[1] He DT, Wang B, Chen JM. Research progress on pharmacological effects of ginsenosides [J]. J Liaoning Univ Tradit Chin Med, 2012, 14: 118-121.

[2] Christensen LP. Ginsenosides: chemistry, biosynthesis, anal- ysis, and potential health effects [J]. Adv Food Nutr Res, 2009, 55: 1-99.

[3] Zuo BM, Gao WY, Dong YY, et al. Progress of the tissue culture in medicinal plant Panax ginseng [J]. Mod Chin Med, 2012, 14: 34-37.

[4] Liu H, Gao WY, Zuo BM, et al. Progress of the tissue culture in Panax quinquefolium L. [J]. Mod Chin Med, 2012, 14: 1-4.

[5] Gao WY, Jia W, Duan HQ, et al. Industrialization of medicinal plant tissue culture [J]. China J Chin Mater Med, 2003, 28: 385-390.

[6] Yu KW, Cao WY, Hahn EJ, et al. Jasmonic acid improves ginsenoside accumulation in adventitious root culture of Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer [J]. Biochem Eng J, 2002, 11: 211-215.

[7] Chen W, Gao WY, Jia W, et al. Advances in studies on tissue and cell culture in medicinal plants of Panax L. [J]. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs, 2005, 36: 616-620.

[8] Dou DQ, Jin L, Chen YJ. Advances and prospects of the study on chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of Panax ginseng [J]. J Shenyang Pharm Univ, 1999, 16: 151-156.

[9] Kobashi K. Relation of intestinal bacteria to pharmacological effects of ginsenosides [J]. Biosci Microflora, 1997, 16: 1-7.

[10] Hasegawa H. Proof of the mysterious efficacy of ginseng: basic and clinical trials: metabolic activation of ginsenoside deglycosylation by intestinal bacteria and esterification with fatty acid [J]. J Pharmacol Sci, 2004, 95: 153-157.

[11] Wang YZ, Chen J, Chu SF, et al. Improvement of memory in mice and increase of hippocampal excitability in rats by ginsenoside Rg1’s metabolites ginsenoside Rh1 and protopanaxatriol [J]. J Pharmacol Sci, 2009, 109: 504-510.

[12] Liu X, Dai JG. Advances in the study of biotransformation of ginsenosides [J]. Ginseng Res, 2010, 22: 19-22.

[13] Zhang YX, Chen XY, Zhao WQ. Advances in studies on biotransformation of ginsenosides [J]. J Shenyang Pharm Univ, 2008, 25: 419-422.

[14] Wang Y, Liu TH, Wang W, et al. Research on the transformation of ginsenoside Rg1 by intestinal flora [J]. China J Chin Mater Med, 2001, 26: 188-190.

[15] Bae EA, Choo MK, Park EK, et al. Metabolism of ginsenoside R(c) by human intestinal bacteria and its related antiallergic activity [J]. Biol Pharm Bull, 2002, 25: 743-747.

[16] Bae EA, Han MJ, Choo MK, et al. Metabolism of 20(S)- and 20(R)-ginsenoside Rg3 by human intestinal bacteria and its relation to in vitro biological activities [J]. Biol Pharm Bull, 2002, 25: 58-63.

[17] Cui YN, Zhang YX, Zhao YQ. Advances in studies on prep- aration of rare ginsenosides by biotransformation [J]. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs, 2009, 40: 676-680.

[18] Dong AL, Cui YJ, Guo HZ, et al. Microbiological transformation of ginsenoside Rg1 [J]. J Chin Pharm Sci, 2001, 10: 114- 118.

[19] Fu JG. Study on the Microbiological Transformation of Ginsenoside[D]. Changchun: Jilin Agricultural University, 2004.

[20] Cheng LQ, Kim MK, Lee JW, et al. Conversion of major ginsenoside Rb1 to ginsenoside F2 by Caulobacter leidyia [J]. Biotechnol Lett, 2006, 28: 1121-1127.

[21] Bao HY, Li L, Zan LF, et al. Ginsenosides Re biotransformation by Rhizopus sp [J]. Mycosystema, 2010, 29: 548-554.

[22] Cui Y, Jiang BH, Han Y, et al. Microbial transformation on ginsenoside compound K from total saponins in fruit of Panax ginseng [J]. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs, 2007, 38: 189-193.

[23] Liu X, Qiao LR, Xie D, et al. Microbial deglycosylation and ketonization of ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 by Fusarium oxysporum [J]. J Asian Nat Prod Res, 2011, 13: 652-658.

[24] Liu X, Qiao LR, Xie D, et al. Microbial transformation of ginsenosides-Rg1 by Absidia coerulea and the reversal activity of the metabolites towards multi-drug resisitant tumor cells [J]. Fitoterapia, 2011, 82: 1313-1317.

[25] Ko SR, Choi KJ, Suzuki K, et al. Enzymatic preparation of ginsenosides Rg2, Rh1, and F1 [J]. Chem Pharm Bull, 2003, 51: 404-408.

[26] Ko SR, Suzuki Y, Suzuki K, et al. Marked production of ginsenosides Rd, F2, Rg3, and compound K by enzymatic me- thod [J]. Chem Pharm Bull, 2007, 55: 1522-1527.

[27] Liu L, Zhu XM, Wang QJ, et al. Enzymatic preparation of 20(S, R)-protopanaxadiol by transformation of 20(S, R)-Rg3 from black ginseng [J]. Phytochemistry, 2010, 71: 1514- 1520.

[28] Liu L, Gu LJ, Zhang DL, et al. Microbial conversion of rare ginsenoside Rf to 20(S)-protopanaxatriol by Aspergillus niger [J]. Biosci Biotechno1 Biochem, 2010, 74: 96-100.

[29] Kim DS, Cue YS, Yu HS, et al. Ginsenoside Rh2 prepared from enzyme reaction [J]. J Dalian Inst Light Ind, 2002, 21: 112-115.

[30] Noh KH, Son JW, Kim HJ, et al. Ginsenoside compound K production from ginseng root extract by a thermostable be- ta-glycosidase from Sulfolobus solfataricus [J]. Biosci Bio- techno1 Biochem, 2009, 73: 316-321.

[31] Yoo MH, Yeom SJ, Park CS, et al. Production of aglycon protopanaxadiol via compound K by a thermostable 阝-glycosidase from Pyrococcus furiosus [J]. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2011, 89: 1019-1028.

[32] Chen SL, Zhu XX, Li CF, et al. Genomics and synthetic biology of traditional Chinese medicine [J]. Acta Pharm Sin, 2012, 47: 1070-1078.

[33] Wang W, Meng C, Zhu P, et al. Preliminary study on metabolic engineering of yeast for producing taxadiene [J]. China Biotechnol , 2005, 25: 103-108.

[34] Ajikumar PK, Xiao WH, Tyo KE, et al. Isoprenoid pathway optimization for taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli [J]. Science, 2010, 330: 70-74.

[35] Kong JQ, Wang W, Wang LN, et al. The improvement of amorpha-4,11-diene production by a yeast-conform variant [J]. JAppl Microb, 2009, 106: 941-951.

[36] Westfall PJ, Pitera DJ, Lenihan JR, et al. Production of amorphadiene in yeast, and its conversion to dihydroartemisinic acid, precursor to the antimalarial agent artemisinin [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2012, 109: E111-118.

[37] Wu Q, Zhou YQ, Sun C, et al. Progress in ginsenosides biosynthesis and prospect of secondary metabolic engineering for the production of ginsenosides [J]. China Biotechnol, 2009, 29: 102-108.

[38] Ming QL, Han T, Huang F, et al. Advances in studies on ginsenoside biosynthesis and its related enzymes [J]. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs , 2010, 41: 1913-1917.

[39] Wu Q, Sun C, Chen SL. Identification and expression analysis of a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene from American ginseng [J]. Plant Omics J, 2012, 5: 414-420.

[40] Kim OT, Bang KH, Jung SJ, et al. Molecular characterization of ginseng farnesyl diphosphate synthase gene and its up- reg- ulation by methyl jasmonate [J]. Biol Plant, 2010, 54: 47-53.

[41] Ali MB, Yu KW, Hahn EJ, et a1. Methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid elicitaion induces ginsenosides accumulation, enzymatic and non-enzymatic anti-oxidant in suspension culture Panax ginseng roots in bioreactors [J]. Plant Cell Rep, 2006, 25: 613-620.

[42] Kim OT, Kim SH, Ohyama K, et al. Upregulation of phytosterol and triterpene biosynthesis in Centella asiatica hairy roots overexpressed ginseng farnesyl diphosphate synthase [J]. Plant Cell Rep, 2010, 29: 403-411.

[43] Lee MH, Jeong JH, Seo JW, et al. Enhanced triterpene and phytosterol biosynthesis in Panax ginseng overexpressing squalene synthase gene [J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2004, 45: 976-984.

[44] Kim TD, Han JY, Huh GH, et al. Expression and functional characterization of three squalene synthase genes associated with saponin biosynthesis in Panax ginseng [J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2011, 52: 125-137.

[45] Seo JW, Jeong JH, Shin CG, et a1. Over expression of squa- lene synthase in Eleutherococcus senticosus increases phytos- terol and triterpene accumulation [J]. Phytochemistry, 2005, 66: 869-877.

[46] Jiang SC, Zhang MZ, Wang Y, et al. Interference vector construction of Panax ginseng’ SQS gene and transformation callus [J]. J Jilin Univisity , 2011, 49: 1136-1140.

[47] Han JY, In JG, Kwon YS, et al. Regulation of ginsenoside and phytosterol biosynthesis by RNA interferences of squalene epoxidase gene in Panax ginseng [J]. Phytochemistry, 2010, 71: 36-46.

[48] Jiang SC, Liu WC, Wang Y, et al. Correlation between ginsenoside accumulation and SQS and SQE gene expression in different organs of Panax quinquefolius [J]. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs, 2011, 42: 579-584.

[49] Kushiro T, Ohno Y, Shibuya M, et a1. In vitro conversion of 2, 3-oxidosqualene into dammarenediol by Panax ginseng microsomes [J]. Biol Pharm Bull, 1997, 20: 292-294.

[50] Tansakul P, Shibuya M, Kushiro T, et al. Dammarenediol-II synthase, the first dedicated enzyme for ginsenoside biosynthesis, in Panax ginseng [J]. FEBS Lett, 2006, 580: 5143-5149.

[51] Han JY, Kwon YS, Yang DC, et al. Expression and RNA interference-induced silencing of the dammarenediol synthase gene in Panax ginseng [J].Plant Cell Physiol, 2006, 47: 1653-1662

[52] Lee MH, Han JY, Kim HJ, et al. Dammarenediol-II production confers TMV tolerance in transgenic tobacco expressing Panax ginseng dammarenediol-II synthase [J]. Plant cell Physiol, 2011, 53: 173-182.

[53] Kushiro T, Shibuya M, Ebizuka Y. 阝-Amyrin synthase cloning of oxidosqualene cyclase that catalyzes the formation of the most popular triterpene among higher plants [J]. Eur J Biochem, 1998, 256: 238-244.

[54] Zhao SJ, Hou CX, Liang YL, et al. Cloning of ginseng 阝-AS gene and the construction of its antisense plant expression vector [J]. China Biotechnol , 2008, 28: 74-77.

[55] Niu YY, Luo HM, Huang LF. Advances in the study of CYP450 involves in ginsenosides biosynthesis [J]. World Sci Technol/Mod Tradit Chin Med Mater Med, 2012, 14: 1177-1183.

[56] Han JY, Kim HJ, Kwon YS, et al. The Cyt P450 enzyme CYP716A47 catalyzes the formation of protopanaxadiol from dammarenediol-II during ginsenoside biosynthesis in Panax ginseng [J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2011, 52: 2062-2073.

[57] Chen SL, Luo HM, Li Y, et al. 454 EST analysis detects genes putatively involved in ginsenoside biosynthesis in Panax ginseng [J]. Plant Cell Rep, 2011, 30: 1593-1601.

[58] Sun C, Li Y, Wu Q, et al. De novo sequencing and analysis of the American ginseng root transcriptome using a GS FLX Titanium platform to discover putative genes involved in ginsenoside biosynthesis [J].BMCGenomics, 2010, 11:

262-273.

[59] Luo HM, Sun C, Sun YZ, et al. Analysis of the transcriptome of Panax notoginseng root uncovers putative triterpene saponin – biosynthetic genes and genetic markers [J]. BMC Genomics, 2011, 12: S5.

[60]Han JY, Hwang HS, Choi SW, et al. Cytochrome P450 CYP716A53v2 catalyzes the formation of protopanaxatriol from protopanaxadiol during ginsenoside biosynthesis in Pa- nax ginseng [J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2012, 53: 1535-1545.

[61] Chen X, Xue Y, Liu JH, et al. Purification and characterization of glucosyltransferase from Panax Ginseng hairy root cultures [J]. Pharm Biotechnol , 2009, 16: 50-54.

[62] Yue CJ, Zhong JJ. Purification and characterization of UDPG: ginsenoside Rd glucosyltransferase from suspended cells of Panax notoginseng [J]. Proc Biochemistry, 2005, 40: 3742-

3748.

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese