What Is Marigold Extract Lutein Powder?

Tagetes erecta, also known as stinking hibiscus or honeycomb chrysanthemum, is an annual herb in the family Asteraceae, native to South America and Mexico. It is tolerant of poor soil and has a wide range of adaptability[1]. It was introduced to China in the 1980s and is now cultivated throughout the country, including in tropical and subtropical regions such as Guangdong and southern Yunnan. There are many varieties of marigolds with different flower colors, including white, pale yellow, yellow, and orange, which have great ornamental value in potted plants, landscaping, and cut flowers. The carotenoid content and types in marigold petals vary, with differences of more than 100 times between different varieties of marigolds[2]. Marigolds can be divided into two categories according to their uses: ornamental and pigment. Among them, pigment marigolds are characterized by high lutein content. Common pigment marigolds at home and abroad include 'Deep Orange 2', 'Scarlet 1', 'King of Chrysanthemum', 'Discovery', 'Champion', 'Antigua', 'Tarzan', 'Miracle', 'Mexican Marigold', etc. Among them, 'King of Chrysanthemum' has a lutein content of up to 28 mg/g in dried flowers[3–6].

Lutein is one of the main pigments in the macular region of the human eye's retina, but the human body cannot synthesize lutein de novo and must obtain it through external intake[7]. Lutein plays an important role in medicine, food processing and nutritional supplements [8], such as an antioxidant to prevent diseases such as macular degeneration [9–10], as a food additive to improve the quality of bread [11], and as an ingredient added to infant formula [12]. In recent years, with the wide application of natural lutein, the domestic market demand has exceeded 1.0×105 t, while the output is less than 1.0×104 t, which is in short supply [13].

Since the pigment in marigold petals is mainly lutein, and the extraction and purification process is simple, it has become one of the main raw materials for extracting lutein [16]. At present, there have been many reviews on plant carotenoids, but there have been no systematic reports on the research progress of marigold lutein. This paper summarizes the research progress of marigold lutein from the aspects of structure and function, extraction process and detection methods, regulation of biosynthesis, esterification and stable storage, and environmental factors affecting lutein synthesis. It also provides an outlook for future research, with the aim of providing a reference for the healthy development of the marigold lutein industry.

1 Lutein structure and function

1.1 Lutein structure

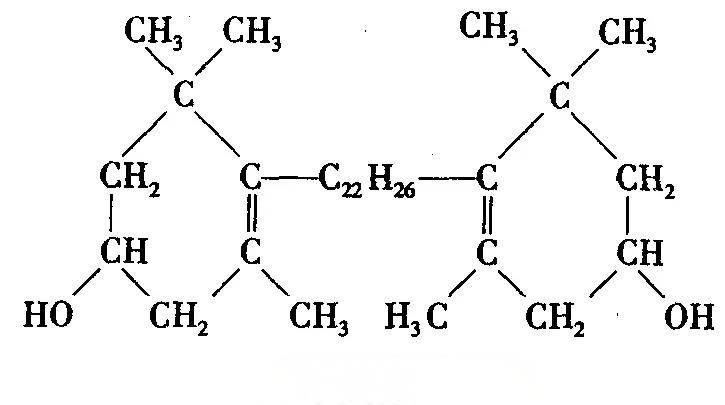

The synthesis of lutein in plants begins with octahydro-tomato red. The carotenoids involved in the biosynthesis pathway are compounds and derivatives with a tetraterpenoid structure. Because they contain conjugated double bonds, there are cis-trans isomers. According to chemical structure, lutein can be divided into cis-lutein and trans-lutein, mostly in the all-trans configuration (Figure 1). According to current literature, there are as many as 32 types of lutein compounds among the carotenoid species of marigolds [17]. Lutein in plants mainly exists in the form of free lutein and esterified lutein esters. Lutein esters are the main compounds naturally present in marigold petals, which mainly consist of six all-trans lutein diesters [18].

1.2 Functions of lutein

In plants, lutein plays an important role in photosynthesis, entomophilous pollination, growth regulation, etc. In terms of photosynthesis, lutein is mainly located in chloroplasts and chromatophores, which helps to improve light absorption and light protection, absorb light energy and transfer it to chlorophyll, and prevent photo-oxidative damage [19–20]. In terms of entomophilous pollination, the accumulation of lutein in plant bodies can help plants form colored tissues, such as blooming flowers and ripe fruits, which appear yellow, orange, and red, thereby promoting pollination and seed dispersal [21–22]. In terms of growth regulation, the synthesis and accumulation of lutein in plants is affected by external temperature, thereby regulating plant growth and development and plant response to environmental changes [23].

2 Lutein extraction process and detection methods

2.1 Lutein extraction process

At present, the extraction processes for lutein from marigold flowers mainly include organic solvent extraction, supercritical carbon dioxide extraction, enzyme-assisted extraction, ultrasonic extraction, microwave extraction, etc. Lutein contains polar functional groups and is easily soluble in polar organic solvents such as hexane, ethanol, isopropanol, chloroform, dichloromethane, and ether. In plants, lutein mainly exists in the form of an ester, and lutein dipalmitate is the main compound in marigold flowers [24]. In the organic solvent extraction method, the lutein fatty acid ester is first extracted using an organic solvent, and then a saponification reaction is carried out with a strong base, KOH, to convert the lutein ester into free lutein. Finally, the lutein is purified by recrystallization [25]. However, the organic solvents used to extract lutein are mainly derived from non-renewable energy sources, and are volatile and toxic, which can cause certain pollution to the ecological environment. Therefore, the organic solvents used to extract lutein are being replaced from non-renewable energy sources to green, environmentally friendly, non-toxic, biodegradable solvents. Some studies have found that 2-methyltetrahydrofuran, a degradable green solvent, can replace organic solvents and be used to extract lutein from plants[26].

In addition, supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) extraction is considered a green extraction process for extracting lutein. The temperature and pressure are used to influence the solubility of lutein fatty acid esters in supercritical CO2, and then saponification is carried out to obtain free lutein [27]. However, the SC-CO2 extraction method also has disadvantages, such as the high pressure parameters required to extract lutein, which is as high as 35 MPa to achieve a high extraction rate [28]. At the same time, compared with SC-CO2 extraction, liquefied propane and liquefied dimethyl ether have lower pressure values and higher lutein extraction rates [29].

The enzyme-assisted method first uses cellulase and pectinase to break down the cell walls, and then uses organic solvent extraction to extract the xanthophyll. After treating marigolds with cellulase and pectinase or protease, the xanthophyll was extracted with an organic solvent, and the content was more than 45% higher than that of the enzyme-free treatment group [30]. Based on the enzymatic hydrolysis of marigold xanthophyll diesters after extraction, the xanthophyll diesters extracted by SC-CO2 extraction and organic solvent extraction were enzymatically hydrolyzed to convert xanthophyll diesters into free xanthophylls. Tests were carried out on the conversion of lutein diesters into free lutein by lipase enzymolysis of lutein diesters extracted with organic solvents and SC-CO2, respectively. The results showed that the conversion rate of lutein diesters extracted with SC-CO2 into lutein by enzymolysis was higher [31].

Ultrasonic extraction uses ultrasound to break cells, while microwave extraction uses microwaves to destroy the plant cell walls. Both methods have the advantages of being short, efficient and having a high extraction rate, which promotes the entry of the solvent into the cells and accelerates the dissolution of the solvent and lutein diester, thereby improving the efficiency of lutein extraction. A study used sunflower seed oil as the solvent to optimize the effect of three factors on the lutein extraction of marigold: ultrasonic intensity, extraction time, and the effect of three factors on the amount of lutein extracted from marigold flowers: ultrasonic intensity, extraction time, and solid-solvent ratio. The results showed that the highest amount of lutein was extracted under the conditions of an ultrasonic intensity of 70 W/m2, an ultrasonic time of 12.5 min, and a solid-solvent ratio of 15.75%, which was much higher than the lutein content extracted by traditional organic solvents [32]. Under certain conditions, ultrasound can significantly increase the lutein ester content in SC-CO2 extracted marigolds [33]. Microwave extraction is a fast, green, and low-energy lutein extraction process, and the lutein extraction amount is three times that of the traditional extraction process [34]. However, compared with conventional enzyme-assisted extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, and Soxhlet extraction of marigold lutein, microwave and enzyme co-assisted aqueous two-phase extraction (MEAATPE) has the highest lutein content [35].

2.2 Methods for detecting lutein

The main methods for detecting lutein are colorimetry, high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), and ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC). Colorimetry is based on Lambert–Beer's law using ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry. Lutein concentration is directly proportional to the absorbance value, and the lutein content can be determined. It has the advantages of being simple to operate and low cost, but it cannot detect lutein isomers and has poor sensitivity. HPLC is based on the chromatographic column, which causes differences in flow rate due to the different adsorption forces of the components in the sample. It separates, identifies and quantitatively analyzes the components. LC-MS relies on HPLC to separate the components, and mass spectrometry is used to identify the mass-to-charge ratio of charged particles. Both methods have high accuracy and stability, and can efficiently detect lutein and its content, but the detection time is relatively long.

3 Regulation of lutein biosynthesis

The biosynthesis pathway of lutein is relatively clear. It is mainly regulated by the geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) produced downstream of the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate pathway (MEP pathway), which serves as the precursor of the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway. Under the catalysis of phytoene synthase (PSY), two GGPPs condense to form a colorless octahydro-tomato red pigment, which is then successively catalyzed by phytoene desaturase (PDS) and PSY) catalyzes the condensation of two GGPP molecules to form a colorless octahydro-tomato red pigment, which is then successively dehydrogenated by a series of enzymes including phytoene desaturase (PDS), ξ-carotene desaturase (ZDS), and ξ-carotene isomerase (15-cis-ξ-carotene isomerase, Z-ISO) is dehydrogenated by a series of enzyme catalysis, followed by the production of lycopene under the catalysis of carotenoid isomerase (CRTISO). Lycopene is formed into α-carotene by lycopene epsilon cyclase (LCYE) and lycopene β-cyclase (LCYB), and then form lutein under the action of enzymes such as β-ring hydroxylase (LUT5) and carotenoid epsilon hydroxylase (LUT1) (Figure 2) [36].

At present, research on the metabolic mechanism of marigold xanthophyll mainly focuses on the genes involved in the metabolic pathway of xanthophyll. Some scholars have found that the high pigment content of marigold flowers may be related to the amplification of related genes in the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway, such as the PSY, PDS, and ZDS genes [6]. In marigolds, PSY is expressed at higher levels in dark yellow petals than in light yellow petals, resulting in a high level of carotenoid accumulation in dark yellow petals [2]. During the development of marigold flowers, the expression of LCYE in marigold petals is positively correlated with the accumulation of lutein [37], and LCYB plays an important role in the synthesis of lutein [38]. The accumulation of lutein in plants is not only related to upstream synthesis enzyme genes such as PSY, LCYE, LCYB, and LUT1/5, but also to degradation enzyme genes such as CCDs and NCEDs (Fig. 2).

Zhang et al. [39] performed qualitative and quantitative analysis of carotenoids and transcriptome sequencing on the 'V-01' (orange flowers) 'inbred line' and the naturally occurring mutant 'V-01M' (yellow flowers) of the marigold plant, summarized the biosynthesis, degradation and accumulation of carotenoids in marigold flowers, and speculated that the carotenoid degradation genes CCDs and NCEDs are important factors in regulating the carotenoid content of marigold flowers. At the same time, in the biosynthesis of lutein, regulatory genes affect the expression of structural genes by encoding transcription factors. Some studies have shown that transient expression of the transcription factor TePTF1 in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) can significantly increase the lutein content [40]; on the contrary, the expression level of the TeIMTF5 gene is negatively correlated with the lutein content. After expressing TeIMTF1 in tobacco, the content of carotenoids such as lutein decreased, indicating that the transcription factor TeIMTF1 plays a negative regulatory role [41]. Recently, Xin et al. [42] assembled a high-quality marigold reference genome and identified genes in its carotenoid metabolic pathway, laying the foundation for a comprehensive analysis of the mechanism of lutein synthesis in marigolds and molecular breeding of marigolds.

4 Esterification and stable storage of lutein

The esterification and stable storage of lutein is also a focus of research. Li et al. [45] reviewed five major types of plastids: protoplasts, etiolated plastids, chloroplasts, starch plastids, and colored plastids, and discussed the effects of plastid type on the accumulation and stability of carotenoids. They described the transformation of plastids and the effects of their chelating ability on the stability of carotenoids. Carotenoids accumulate mainly in the chromatoplasts, where lutein is mainly stored in the plastidial microsomes in the form of lutein esters. Lutein esterification can significantly affect lutein accumulation. Lutein esterification is generally catalyzed by esterase/lipase/thioesterase, such as lutein esterase and lutein acyltransferase, to promote the transfer of fatty acid acyl donors to the lutein hydroxyl acceptor (Figure 2) [46]. Recent studies have found that the lutein esterase genes BjA02.PC1 and BjB04.PC2 in Brassica juncea can redundantly regulate the synthesis of lutein esters, while BjFBN1b encodes a fibrin that promotes the stable storage of lutein esters in plastidic droplets [47].

Studies have shown that virus-mediated expression of the bacterial crtB gene in plants can lead to a decrease in photosynthetic activity and an upregulation of the expression of carotenoid synthesis enzyme genes, enhancing carotenoid storage capacity and thus promoting the transformation of chloroplasts into colored bodies [48]. With the discovery of the regulatory gene Orange (OR) related to plastid transformation, many important advances have been made in the transformation of green bodies into colored bodies. Transformation of the OR gene from cauliflower (Brassica oleracea) into potato (Solanum tuberosum) resulted in a continuous accumulation of carotenoids during 5 months of cold storage of the tubers, which was positively correlated with the number of carotenoid-lipoprotein chelate substructures in the chromoplast [49]. Studies on natural mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana with the allele OR gene mutation to ORHis showed that ORHis interacts with the key regulator of chloroplast division, ARC3 (accumulation and replication of chloroplasts 3) protein, which in turn interferes with the interaction between ARC3 and PARC6 (paralog of ARC6), thereby limiting the division of chromoplasts and reducing the accumulation of carotenoids [50].

In summary, the stable storage of lutein is related to its esterification and plastidic small bodies. The OR gene is closely related to the division of chromatids and the formation of carotenoid-lipoprotein chelate substructures, which not only promote the chelation of newly synthesized carotenoids, but also contribute to the stable storage and accumulation of carotenoids. However, there have been few studies on the storage of marigold lutein in chromoplasts. One study found that the accumulation of lutein in marigold flowers as they develop may be related to the quantity and quality of lipid vesicles in chromoplasts, as observed by transmission electron microscopy (Figure 3) [51]. Overexpression of the marigold TeXES gene in pale yellow petunia flowers can significantly increase the lutein ester content in the corolla and corolla tube [44], suggesting that lutein esterification may play an important role in increasing the lutein content of marigolds.

5 Environmental factors affecting lutein synthesis

Light, temperature, CO2 concentration, mineral elements and hormones can all affect the synthesis of plant xanthophylls, resulting in differences in their accumulation. In plants, photosynthesis, photoprotection and antioxidant activity are closely related to carotenoid metabolism. Marigold seeds were germinated under long (16 h light/8 h dark, same as below), medium (12 h light/12 h dark) and short (8 h light/16 h dark) photoperiods until the third pair of true leaves fully expanded. The results showed that marigold leaves transplanted after treatment with a medium photoperiod had the highest lutein content [52]. After the transfer of CmBCH1 and CmBCH2 in Arabidopsis, high light induced the synthesis and accumulation of high levels of lutein in Arabidopsis leaves [53]. Red light can promote the accumulation of carotenoids during fruit ripening [54– 55] and increase the lutein content of mung bean (Vigna radiata) sprouts [56]. Blue light can induce carotenoid synthesis in fruits [57], upregulate LCYE and downregulate LCYB to change the composition of carotenoids, resulting in a decrease in the content of 9-cis-zeaxanthin and an increase in the content of lutein [58]. However, for carrots (Daucus carota), when the roots of carrots are exposed to light, it can lead to a decrease in carotenoid content and the formation of chloroplasts [59].

Temperature is involved in regulating the accumulation of carotenoids in many plants, but its effect varies among different plants. High temperatures inhibit the expression of carotenoid biosynthesis genes and activate the expression of carotenoid degradation genes in Osmanthus fragrans, resulting in a decrease in the content of carotenoids such as lutein and zeaxanthin. However, low temperatures can increase the content of carotenoids such as lutein [23]. However, during the grain filling process in wheat (Triticum aestivum) seeds, an increase in temperature is beneficial for the esterification of lutein [60].

Some studies have shown that increasing the CO2 concentration in the culture room can significantly increase the carotenoid content of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) fruits, and the lutein content increases during the ripening stage [61]. In addition, Portulaca oleracea cultivated in nutrient solutions with different zinc concentrations showed an increase in the lutein content of the edible parts when cultivated in a nutrient solution with a zinc concentration of 5.2 mg/L [62]. However, selenium treatment of kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) showed that selenium accumulation in kale did not affect the concentration of lutein [63]. However, there have been few studies on the effects of environmental factors on lutein synthesis in marigolds. Recent studies have shown that exogenous application of gibberellins is beneficial for lutein accumulation in marigolds, and that the treatment is best done during the blooming period of the top flowers [64].

6 Outlook

Lutein has multiple effects and the human body cannot synthesize it, so it can only be ingested from the outside. With the growing demand for lutein, marigolds, as an important raw material for lutein extraction, optimizing the lutein extraction process and testing methods, revealing its biosynthesis and metabolic regulation mechanisms, and elucidating its esterification and stable storage laws are prerequisites for ensuring the healthy development of the marigold lutein industry.

The form of lutein in marigolds is mostly in the form of esters, with a small amount of free lutein. Research on the structure of lutein esters can provide a reference for later extraction processes, synthetic regulation and stable storage. When extracting marigold lutein for industrial production, priority should be given to selecting extraction processes that are cost-effective, environmentally friendly and efficient, and then optimizing the process to further improve the lutein extraction rate. The pathway of lutein synthesis is relatively clear, but there is currently little research on the regulatory genes related to the biosynthesis of lutein in marigolds, and even less research on stable storage. Further in-depth research is needed. Lutein in marigold petals is mainly lutein, and zeaxanthin, which has higher economic value, is extremely low. Breeding new varieties of marigolds with high zeaxanthin content is an important direction for future breeding. With the analysis of the marigold genome sequence and the establishment of a marigold transgenic system, the research on the metabolic regulation mechanism of marigold lutein will be greatly accelerated, laying the foundation for the breeding of new marigold strains with high quality and high lutein content through molecular breeding techniques.

Reference

[1] HE Y H, NING G G, SUN Y L, et al. Identification of a SCAR marker linked to a recessive male sterile gene (Tems) and its application in breeding of marigold (Tagetes erecta) [J]. Plant Breed, 2009, 128(1): 92–96.

[2] MOEHS C P, TIAN L, OSTERYOUNG K W, et al. Analysis of carotenoid biosynthetic gene expression during marigold petal development [J]. Plant Mol Biol, 2001, 45(3): 281–293. doi: 10.1023/a:1006417009203.

[3] CHEN R, XIAN X L, ZHONG J J. Quality differences and efficient cultivation techniques of new pigmented marigold varieties at different altitude regions in Sichuan [J]. Sichuan Agric Sci Technol, 2023(7): 38–41.

[4] TIAN L, FENG G D, LIU Y, et al. Comparison of agronomic traits and xanthophyll content among different varieties of Tagetes erecta [J]. J Hefei Univ Technol (Nat Sci), 2018, 41(5): 703–707.

[5]CHI-MANZANERO B, ROBERT M L, RIVERA-MADRID R. Extraction of total RNA from a high pigment content plant marigold (Tagetes erecta) [J].Mol Biotechnol, 2000, 16(1): 17–21. doi: 10.1385/MB:16:1:17.

[6] FENG G D, HUANG S X, LIU Y, et al. The transcriptome analyses of Tagetes erecta provides novel insights into secondary metabolite biosynthesis during flower development [J]. Gene, 2018, 660: 18–27.

[7] LI L H, LEE J C Y, LEUNG H H, et al. Lutein supplementation for eye diseases [J]. Nutrients, 2020, 12(6): 1721. doi: 10.3390/nu12061721 .

[8] ZAFAR J, AQEEL A, SHAH F I, et al. Biochemical and immunological implications of lutein and zeaxanthin [J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 22(20): 10910.

[9] ROWICKA M, MROWICKI J, KUCHARSKA E, et al. Lutein and zeaxanthin and their roles in age-related macular degeneration-neurodegenerative disease [J]. Nutrients, 2022, 14(4): 827.

[10]OCHOA B M, MOJICA C L, HSIEH LO M, et al. Lutein as a functional food ingredient: Stability and bioavailability [J]. J Funct Foods, 2020, 66: 103771.

[11] KWON H, LEE D U, LEE S. Lutein fortification of wheat bread with marigold powder: impact on rheology, water dynamics, and structure [J]. J Sci Food Agric, 2023, 103(11): 5462–5471.

[12]LONG A C, KUCHAN M, MACKEY A D. Lutein as an ingredient in pediatric nutritionals [J]. J AOAC Int, 2019, 102(4): 1034–1043.

[13] HAN L, LUO T, WANG H. Introduction to the current situation of marigold planting industry development and development countermeasures in Qingcheng County [J]. Kexue Zhongyang, 2021(6): 5–6.

[14] YU S J. Study on climate adaptability of Tageteserecta L planting in Longdong area of Gansu province [J]. ChinAgric Sci Bull, 2024, 40(2): 97–101.

[15] CHEN Y L, GUO S F. Problems and countermeasures for the development of marigold industry in Yanshan county [J]. Primary Agric Technol Ext, 2023,11(6): 119–121.

[16] RODRIGUES D B, MERCADANTE A Z, MARIUTTI L R. Marigold carotenoids: much more than lutein esters [J]. Food Res Int, 2019, 119: 653–664.doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.10.043.

[17]OLENNIKOV D N, KASHCHENKON I. Marigold metabolites: Diversity and separation methods of Calendula genus phytochemicals from 1891 to 2022[J]. Molecules, 2022, 27(23): 8626. doi: 10.3390/molecules27238626 .

[18]LI W, GAO Y X, ZHAO J, et al. Phenolic, flavonoid, and lutein ester content and antioxidant activity of 11 cultivars of Chinese marigold [J]. J Agric FoodChem, 2007, 55(21): 8478–8484. doi: 10.1021/jf071696j.

[19]CAZZANIGA S, BRESSAN M, CARBONERA D, et al. Differential roles of carotenes and xanthophylls in photosystem I photoprotection [J].Biochemistry, 2016, 55(26): 3636–3649. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00425.

[20] LEONELLI L, BROOKS M D, NIYOGI K K. Engineering the lutein epoxide cycle into Arabidopsis thaliana [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2017, 114(33):E7002–E7008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704373114.

[21]GAO M, QU H, GAO L, et al. Dissecting the mechanism of Solanum lycopersicum and Solanum chilense flower colour formation [J]. Plant Biol, 2015, 17(1): 1–8. doi: 10.1111/plb.12186.

[22] RONEN G, CARMEL-GOREN L, ZAMIR D, et al. An alternative pathway to β-carotene formation in plant chromoplasts discovered by map-based cloning of Beta and old-gold color mutations in tomato [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2000, 97(20): 11102–11107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190177497.

[23] WANG Y G, ZHANG C, XU B, et al. Temperature regulation of carotenoid accumulation in the petals of sweet osmanthus via modulating expression of carotenoid biosynthesis and degradation genes [J]. BMC Genom, 2022, 23(1): 418. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08643-0.

[24]ABDEL-AAL E S M, RABALSKI I. Composition of lutein ester regioisomers in marigold flower, dietary supplement, and herbal tea [J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2015, 63(44): 9740–9746. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04430.

[25]WANG T T, HAN J, TIAN Y, et al. Combined process ofreaction, extraction, and purification of lutein in marigold flower by isopropanol-KOH aqueous two-phase system [J]. Sep Sci Technol, 2016, 51(9): 1490–1498.

[26] DERRIEN M, BADR A, GOSSELIN A, et al. Optimization of a green process for the extraction of lutein and chlorophyll from spinach by-products using response surface methodology (RSM) [J]. LWT-Food Sci Technol, 2017, 79: 170–177.

[27] GONG Y, PLANDER S, XU H G, et al. Supercritical CO2 extraction of oleoresin from marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) flowers and determination of its antioxidant components with online HPLC-ABTS·+ assay [J]. J Sci Food Agric, 2011, 91(15): 2875–2881.

[28] ESPINOSA-PARDO F A, NAKAJIMA V M, MACEDO G A, et al. Extraction of phenolic compounds from dry and fermented orange pomace using supercritical CO2 and cosolvents [J]. Food Bioprod Process, 2017, 101: 1–10.

[29] BOONNOUN P, TUNYASITIKUN P, CLOWUTIMON W, et al. Production of free lutein by simultaneous extraction and de-esterification of marigold flowers in liquefied dimethyl ether (DME)-KOH-EtOH mixture [J]. Food Bioprod Process, 2017, 106: 193–200.

[30] BARZANA E, RUBIO D, SANTAMARIA R I, et al. Enzyme-mediated solvent extraction of carotenoids from marigold flower (Tagetes erecta) [J]. J

Agric Food Chem, 2002, 50(16): 4491–4496.

[31] MORA-PALE J M, PÉREZ-MUNGUÍA S, GONZÁLEZ-MEJÍA J C, et al. The lipase-catalyzed hydrolysis of lutein diesters in non-aqueous media is favored at extremely low water activities [J]. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2007, 98(3): 535–542. doi: 10.1002/bit.21417.

[32] MANZOOR S, RASHID R, PRASAD PANDA B, et al. Green extraction of lutein from marigold flower petals, process optimization and its potential to improve the oxidative stability of sunflower oil [J]. Ultrason Sonochem, 2022, 85: 105994.

[33] GAO Y X, NAGY B, LIU X, et al. Supercritical CO2 extraction of lutein esters from marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) enhanced by ultrasound [J]. J Supercrit Fluids, 2009, 49(3): 345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2009.02.006.

[34]MARY LEEMA J T, PERSIA JOTHY T, DHARANI G. Rapid green microwave assisted extraction of lutein from Chlorella sorokiniana (NIOT-2)-process optimization [J]. Food Chem, 2022, 372: 131151. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131151 .

[35] FU X Q, MA N, SUN W P, et al. Microwave and enzyme co-assisted aqueous two-phase extraction of polyphenol and lutein from marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) flower [J]. Ind Crop Prod, 2018, 123: 296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.06.087.

[36]TANAKA Y, SASAKI N, OHMIYA A. Biosynthesis of plant pigments: Anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids [J]. Plant J, 2008, 54(4): 733–749.

[37]ZHANG C L, WANG Y Q, WANG W J, et al. Functional analysis of the marigold (Tagetes erecta) lycopene ε-cyclase (TeLCYe) promoter in transgenic tobacco [J]. Mol Biotechnol, 2019, 61(9): 703–713. doi: 10.1007/s12033-019-00197-z.

[38] DEL VILLAR-MARTÍNEZ A A, GARCÍA-SAUCEDO P A, CARABEZ-TREJO A, et al. Carotenogenic gene expression and ultrastructural changes during development in marigold [J]. J Plant Physiol, 2005, 162(9): 1046–1056.

[39] ZHANG H L, ZHANG S Y, ZHANG H, et al. Carotenoid metabolite and transcriptome dynamics underlying flower color in marigold (Tagetes erecta L.)[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1): 16835. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73859-7.

[40] NIU X L, FENG G D, HUANG S X, et al. Transcription factor gene regulating lutein synthesis and its application: CN107365778B [P].

[41] NIU X L, HUANG S X, FENG G D, et al. A marigold transcription factor gene and its application: CN108220300B [P]. 2021-04-13.

[42]XIN H B, JI F F, WU J, et al. Chromosome-scale genome assembly of marigold (Tagetes erecta L.): An ornamental plant and feedstock for industrial lutein production [J]. Hort Plant J, 2023, 9(6): 1119–1130.

[43]SUN T H, YUAN H, CAO H B, et al. Carotenoid metabolism in plants: the role of plastids [J]. Mol Plant, 2018, 11(1): 58–74.

[44] KISHIMOTO S, ODA-YAMAMIZO C, OHMIYA A. Heterologous expression of xanthophyll esterase genes affects carotenoid accumulation in petunia corollas [J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1): 1299. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58313-y.

[45] LI L, YUAN H, ZENG Y L, et al. Plastids and carotenoid accumulation [M]// STANGE C. Carotenoids in Nature. Cham: Springer, 2016: 273–293.

[46] WATKINS J L, LI M, MCQUINN R P, et al. A GDSL esterase/lipase catalyzes the esterification of lutein in bread wheat [J]. Plant Cell, 2019, 31(12):3092–3112. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00272.

[47]LI R H, ZENG Q Y, ZHANG X X, et al. Xanthophyll esterases in association with fibrillins control the stable storage of carotenoids in yellow flowers of rapeseed (Brassica juncea) [J]. New Phytol, 2023, 240(1): 285–301. doi: 10.1111/nph.18970.

[48] LLORENTE B, TORRES-MONTILLA S, MORELLI L, et al. Synthetic conversion of leaf chloroplasts into carotenoid-rich plastids reveals mechanistic basis of natural chromoplast development [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2020, 117(35): 21796–21803.

[49]LI L, YANG Y, XU Q, et al. The Or gene enhances carotenoid accumulation and stability during post-harvest storage of potato tubers [J]. Mol Plant, 2012,5(2): 339–352. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr099.

[50] SUN T H, YUAN H, CHEN C, et al. ORHis, a natural variant of OR, specifically interacts with plastid division factor ARC3 to regulate chromoplast number and carotenoid accumulation [J]. Mol Plant, 2020, 13(6): 864–878.

[51]DEL VILLAR-MARTÍNEZ A A, VANEGAS-ESPINOZA P E, PAREDES-LÓPEZ O. Marigold regeneration and molecular analysis of carotenogenic genes [M]// JAIN S M, OCHATT S J. Protocols for in vitro Propagation of Ornamental Plants. Humana: Humana Press, 2010, 589: 213–221.

[52] CHEN Q, TIAN F M, HE J J, et al. Effects of different photoperiod treatments on flower yield and quality of Tagetes erecta [J]. J Cold-Arid Agric Sci,2023, 2(7): 611–614.

[53] HAN S, WANG Y J, ZHANG Q C, et al. Chrysanthemum morifolium β-carotene hydroxylase overexpression promotes Arabidopsis thaliana tolerance to high light stress [J]. J Plant Physiol, 2023, 284: 153962. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2023.153962 .

[54]HUANG X L, HU L P, KONG W B, et al. Red light-transmittance bagging promotes carotenoid accumulation of grapefruit during ripening [J]. Commun Biol, 2022, 5(1): 303. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03270-7.

[55] GONG J L, ZENG Y L, MENG Q N, et al. Red light-induced kumquat fruit coloration is attributable to increased carotenoid metabolism regulated by FcrNAC22 [J]. J Exp Bot, 2021, 72(18): 6274–6290.

[56] CHENG Y Y, XIANG N, CHEN H L, et al. The modulation of light quality on carotenoid and tocochromanol biosynthesis in mung bean (Vigna radiata)sprouts [J]. Food Chem Mol Sci, 2023, 6: 100170. doi: 10.1016/j.fochms.2023.100170.

[57] NI J B, LIAO Y F, ZHANG M M, et al. Blue light simultaneously induces peel anthocyanin biosynthesis and flesh carotenoid/sucrose biosynthesis in mango fruit [J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2022, 70(50): 16021–16035. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c07137.

[58] MA G, ZHANG L C, KITAYA Y, et al. Blue LED light induces regreening in the flavedo of Valencia orange in vitro [J]. Food Chem, 2021, 335: 127621.

[59] QUIAN-ULLOA R, STANGE C. Carotenoid biosynthesis and plastid development in plants: The role of light [J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 22(3): 1184.

[60] MATTERA M G, HORNERO-MÉNDEZ D, ATIENZA S G. Lutein ester profile in wheat and tritordeum can be modulated by temperature: Evidences for regioselectivity and fatty acid preferential of enzymes encoded by genes on chromosomes 7D and 7Hch [J]. Food Chem, 2017, 219: 199–206.

[61]ZHANG Z M, LIU L H, ZHANG M, et al. Effect of carbon dioxide enrichment on health-promoting compounds and organoleptic properties of tomato fruits grown in greenhouse [J]. Food Chem, 2014, 153: 157–163.

[62] D'IMPERIO M, DURANTE M, GONNELLA M, et al. Enhancing the nutritional value of Portulaca oleracea L. by using soilless agronomic biofortification with zinc [J]. Food Res Int, 2022, 155: 111057. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111057 .

[63]LEFSRUD M G, KOPSELL D A, KOPSELL D E, et al. Kale carotenoids are unaffected by, whereas biomass production, elemental concentrations, and selenium accumulation respond to, changes in selenium fertility [J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2006, 54(5): 1764–1771.

[64] GUO H, LYU X N, MU J M, et al. Effects of exogenous Gibberellin (GA3) on agronomic characters and lutein content of marigold [J]. ActaAgric Jiangxi,2023, 35(6): 94–100.

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese