Study on Synthetic Lycopene Powder

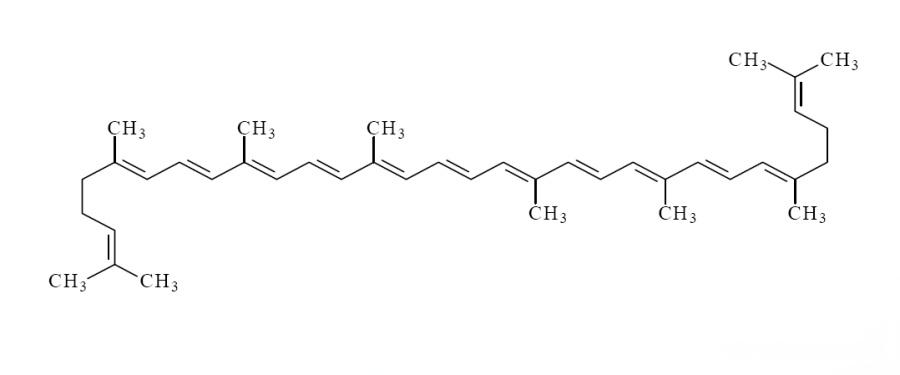

Lycopene (C40H56) is a natural fat-soluble pigment of plant and microbial origin. Chemically, it is a carotenoid composed of a straight-chain hydrocarbon with 11 conjugated double bonds and 2 non-conjugated double bonds [1]. Lycopene can effectively scavenge free radicals in the body and quench singlet oxygen. Its ability to quench singlet oxygen is 2 times that of β-carotene and 10 times that of α-tocopherol[2]. It can be used as an effective antioxidant to reduce the damaging effects of oxidative stress on cells. More and more studies have shown that lycopene has a protective or intervention effect on chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, malignant tumors and Alzheimer's disease, and therefore attracts much attention in the fields of food, chemical industry and medicine. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the Codex Committee on Food Additives (CCFA), and the World Health Organization (WHO) have identified lycopene as a Class A nutrient [3].

With the increasing recognition of natural functional products, research on lycopene as a functional food additive is also deepening. However, the human body cannot synthesize lycopene directly and can only obtain it from natural vegetables and fruits or intestinal flora, and its sources and quantities are quite limited. This article focuses on the relationship between the main structure of lycopene powder, bioavailability and influencing factors, the microbial synthesis pathway, the synthesis strategies of three yeast strains for producing lycopene, and the relationship and role of the application of lycopene in the prevention of chronic diseases. It provides a theoretical basis for the production, utilization and functional exploration of lycopene.

1 Chemical structure and bioavailability of lycopene and its analogues

The molecular structure of the lycopene molecule contains 13 double bonds, 11 of which are conjugated, which makes lycopene unstable and prone to isomerization under the influence of light, oxygen, acids, catalysts or other environmental changes. Lycopene mainly exists in two conformations: the all-E-isomer (all-trans isomer) and the Z-isomer (cis-trans isomer) (Figure 1). More than 90% of the natural lycopene in fruits and vegetables exists in the thermodynamically most stable all-E-isomer form [4]; however, studies have found that more than 50% of the lycopene in human serum and tissues is metabolized in the form of the Z-isomer [4]. The common Z-isomers are mainly 5-cis, 9-cis, 13-cis and 15-cis lycopene. Studies have shown that 5-cis lycopene has higher antioxidant capacity and higher bioavailability than other analogues [5].

Therefore, the intake of 5-cis lycopene may be more beneficial to human health than all-E-lycopene, and has greater potential for application in the food and pharmaceutical industries. In recent years, scholars have been working hard to develop methods for obtaining high concentrations of Z-lycopene, such as heat treatment, microwave treatment, light irradiation, electrolysis treatment and catalytic treatment. However, there is still room for improvement in these methods. For example, heating and microwave treatment may cause degradation due to high temperatures; photochemical treatment may also cause degradation due to the conversion of the all-E-isomer. Although the use of photosensitizers can effectively prevent the photodegradation of lycopene, it brings the challenge of photosensitizer removal. Similarly, if chemical reagents such as electrolytes and catalysts are used, the removal of toxic substances is also a great challenge.

There are two main reasons that affect the bioavailability of lycopene powder: whether lycopene is completely released from the food matrix and the strength of lycopene-dependent lipid emulsification and micelle formation [6] (Figure 2). Due to the extremely hydrophobic chemical structure of lycopene, the direct absorption and utilization rate of lycopene in fruits and vegetables by the human body is very low [7]. However, processes such as heat treatment during food processing can damage cell membranes and promote the release of lycopene from the tissue matrix, thereby increasing the bioavailability of lycopene. The bioavailability of lycopene varies greatly depending on the processing method, with the order of magnitude being: thermally processed and purified oily preparations > mild processing > raw tomatoes [8]. In order to further improve the effective utilization of lycopene, researchers have successfully developed lycopene delivery systems such as traditional emulsions, nanoemulsion carriers, and nanostructured lipid carriers based on their physicochemical properties and characteristics such as the structure of body cells (Figure 3). These systems can greatly improve the bioavailability of lycopene by “packaging” to increase the water solubility and bioavailability of the active ingredients, protecting them from the adverse conditions of the digestive tract, and releasing them at the absorption site for better absorption.

2 Biosynthesis of lycopene

Natural lycopene is mainly derived from tomatoes and fruits such as grapefruit, melons, red guava, red carrots, and wolfberries. In addition, studies have confirmed that some microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi and algae, can accumulate lycopene under specific physiological conditions [9]. For example, the inactivation of lycopene cyclase leads to the interruption of the carotenoid pathway, which helps lycopene accumulate in Blakeslea trispora [10]. The Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) has approved three sources of lycopene: tomato extract, chemical synthesis, and Blakeslea trispora extract.

Among them, the tomato extraction method mainly uses vegetable and fruit raw materials rich in lycopene, which are extracted efficiently using various extractants. The advantage of this method is that it can achieve high-quality natural lycopene production in batches, but this method is susceptible to external factors such as the species, origin, and harvest season of the raw materials, which can affect the yield. In addition, large amounts of waste residue, waste liquid, and waste gas are generated during industrial production, which results in high comprehensive treatment costs. The chemical synthesis method is relatively mature, with mild reaction conditions, high recovery rates and low costs. It is currently the main technology for the industrial production of lycopene. However, lycopene has many C=C double bonds, making it difficult to control stereoselectivity. The reaction process is complex and has high technical requirements. There is also the safety issue of organic solvent pollution from the chemical reagents left over from the reaction. In recent years, with the analysis by scientists of the biosynthetic pathway of natural lycopene powder and the great progress in modern microbial genetic engineering, other microorganisms (such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris and Yarrowia lipolytica) can also be used as hosts for lycopene production. Because they have the incomparable advantages of no seasonal restrictions, high yield and a single product, they provide a new way of thinking for the large-scale industrial production of lycopene and have attracted the attention of researchers and the food and pharmaceutical industries.

2.1 Biosynthetic pathway of lycopene

In living organisms, lycopene is synthesized mainly through two biosynthetic pathways: the mevalonate (Mevalonate, MVA) pathway and the 2-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (2-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate, MEP) pathway. Among them, eukaryotes mainly synthesize lycopene and its derivatives through the MVA pathway, while prokaryotes often synthesize them through the MEP pathway. Both biosynthetic pathways use glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P), which is produced by the body's sugar metabolism, to catalyze a series of secondary metabolic enzymes to synthesize intermediate molecules such as isopentenyl pyrophosphate (Isopentenyl pyrophosphate, IPP) and its isomer 3,3-dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) and other intermediate molecules. Subsequently, IPP and DMAPP are condensed, modified and elongated by enzymes to finally synthesize lycopene (Figure 4).

2.2 Metabolic engineering of yeast for lycopene synthesis

In nature, yeasts such as Rhodotorula glutinis, Rhodotorula graminis and Phaffia rhodozyma can synthesize carotenoid natural products autonomously, but the amount and biological activity of the synthesized products often cannot meet the needs of industrial production [11]. However, the commonly used industrial fermentation yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris and Yarrowia lipolytica are highly safe, have mature genetic modification tools, and have been genetically modified for the research and production of lycopene [12]. In response to the lack of a complete metabolic system in S. cerevisiae and Y. lipolytica, and the fact that the metabolic process of carotenoid synthesis stops at the geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) step [13], scholars have proposed various strategies for constructing lycopene-producing yeast strains (Table 1). However, improving the final lycopene titer and yield remains a major challenge. There are more strategies reported for S. cerevisiae than for P. pastoris and Y. lipolytica, but there are fewer systematic engineering studies on S. cerevisiae to achieve high lycopene production. The source of the heterologous pathway components and the efficiency of the pathway are key to lycopene production in S. cerevisiae [14], and the low yield is most likely caused by the lack of coordination between the endogenous pathway and the heterologous pathway.

Therefore, in order to further explore the adaptability of S. cerevisiae itself and the heterologous pathway, SHI B et al. [6] provided an effective solution by screening for genes from different sources such as bacteria, yeast, fungi, algae and plants that are involved in the biosynthesis of lycopene, including crtE (encoding GGPP synthase), crtB (encoding octahydro-lycopene synthase) and crtI (encoding octahydro-lycopene dehydrogenase) to improve catalytic activity; the combination of the screened genes avoids the loss of key steps due to an imbalance between endogenous and exogenous metabolic pathways; knocking out endogenous bypass genes increases the supply of the precursor acetyl coenzyme A (Acetyl coenzyme A, acetyl-CoA) supply and balanced NADPH utilization, a pure glucose induction system was achieved, and a strain with the highest yield, BS106 (lycopene yield of 3.28 g/L), was constructed. This strain provides a reference for improving the compatibility of S. cerevisiae's heterologous pathway for producing valuable substances with the endogenous background. Currently, the microbial production of isoprenoid compounds, including lycopene, faces two potential challenges: the natural MVA or MEP pathway is limited by cofactors; and most long-chain isoprenoid compounds are mainly stored in a limited space due to their hydrophobicity, which will prevent their large-scale accumulation [15].

To solve both problems, LUO Z S et al. [16] introduced the isopentenol utilization pathway (IUP), which converts isopentenol directly to IPP, enhances the MVA pathway, and increases the flux of IPP and downstream products [14]. Combining IUP with high hydrophobicity converts Y. lipolytica into a lipid-producing organism that is more conducive to the accumulation of lipid-soluble isopentenyl compounds. These strategies can be widely used for commercial purposes. P. pastoris was selected as a producer of carotenoid substances because it also has important commercial advantages. P. pastoris has high cell quality and can grow to higher densities than other yeasts such as S. cerevisiae without accumulating ethanol and using various types of organic matter as carbon sources. Therefore, BHATAYA A et al. [17] first applied metabolic engineering technology to P. pastoris, designing and constructing two plasmids: the pGAPZB-EpBPI*P plasmid encodes the targeted superoxide dismutase, while the pGAPZB-EBI* plasmid encodes the untargeted enzyme. After these two plasmids were transformed into P. pastoris, a high-yielding lycopene-producing strain of P. pastoris V-type clone containing the pGAPZB-EpBPI*P plasmid could be screened, laying the foundation for the development of lycopene production using P. pastoris.

With the rapid development of synthetic biology, protein engineering and metabolic engineering, genetically engineered yeast has not only improved the production efficiency of lycopene, but also increased the utilization of low-cost substrates, further reducing production costs. Synthetic microorganisms will undoubtedly provide new options for the heterologous synthesis of natural products.

3 Antioxidant bioactivity of lycopene

Studies have found that there is a link between the development and progression of chronic diseases such as malignant tumours and oxidative stress. Lycopene, as a natural antioxidant, has the effect of reducing the harm caused by oxidative stress. The main antioxidant activity of lycopene powder is to act on free radicals such as hydrogen peroxide, nitrogen dioxide and hydroxyl radicals to combat the oxidation of proteins, lipids and DNA. When lycopene is exposed to oxidants or free radicals, the double bonds can be cleaved or increased, destroying the polyene chain. Possible reactions of lycopene with active substances are [32]: the formation of adducts, electron transfer to free radicals and the extraction of hydrogen from alleles (Figure 5). The following description focuses on the relationship between several chronic diseases and oxidative stress and how lycopene inhibits the mutations that lead to chronic diseases.

Tumor cells usually have excessively high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [33] and experience oxidative stress. ROS are normal metabolic products of cells that play a key role in signal transduction. High levels of ROS in tumor cells are involved in various stages of tumorigenesis, such as tumor cell growth, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis [34]. It has been found that lycopene and cisplatin have a synergistic effect in inhibiting the growth of human cervical carcinoma (HeLa) cells. The 72-hour survival rates of HeLa cells treated with lycopene (10 μmol/L) and cisplatin (1 μmol/L) alone were 65.6% and 71.1%, respectively, and the cell viability decreased to 37.4% after the combination. In addition, compared with the control group, the lycopene-treated cell group showed increased expression of nuclear factor E2-related factor (NRF2), and the NRF2 level in the combined group was significantly higher than that in the cisplatin-treated cell group alone. These results indicate that lycopene is likely to exert an anticancer effect by activating NRF2 to mediate oxidative stress [35] (Figure 6).

Abnormal NRF2 signal regulation is associated with many oxidative stress-related diseases. Activation of NRF2 is considered to be a way to induce antioxidant capacity and alleviate pathology, mainly through the induction of antioxidant enzymes mediated by the NRF2 signal. In another study, it was found that lycopene can inhibit the activation of nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and the expression of NF-κB target genes (cIAP1, cIAP2, and survivin) by reducing intracellular and mitochondrial ROS levels, inducing apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells PANC-1. These findings suggest that lycopene supplementation may potentially prevent pancreatic cancer [36].

Inflammation is the body's own defence response. In the normal body balance, inflammation serves to eliminate the initial factors causing cell damage, dispose of necrotic cells and damaged tissue caused by damage and inflammation, and carry out tissue repair. This natural response, acute inflammation, is a key survival mechanism used by all higher vertebrates [37-38]. However, if acute inflammation cannot be resolved, it may lead to chronic inflammation and can be a destructive process. Damaged tissue releases pro-inflammatory cytokines and other biological inflammatory mediators into the body's circulatory system, thus transforming low-grade tissue inflammation into systemic inflammation [39]. In addition, autoimmune diseases and long-term exposure to irritants can also lead to a systemic inflammatory state. An excessive inflammatory response will adversely affect the body's repair, and cells may become cancerous under prolonged stimulation of inflammatory infiltration [40]. Studies have reported that lycopene can improve the mitochondrial disorder induced by lipopolysaccharide in the brain and liver of mice, reduce the expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-a, IL-1β and IL-6, and alleviate neuroinflammation and hepatitis [41].

4 Conclusions and prospects

This paper provides a systematic review of recent research progress on the structure, bioavailability, heterologous microbial synthesis strategies, and protection against oxidative stress in chronic diseases of lycopene powder. Lycopene is a member of the carotenoid family, and its antioxidant capacity has significant health benefits. This property has generated strong interest in its use in food formulations. To use this compound, it is necessary to ensure that the extraction and retention processes fully consider the factors affecting the stability and bioavailability of lycopene in order to obtain a highly effective and highly usable functional product.

There are many traditional extraction techniques for bioactive substances, including mechanical and ultrasonic extraction, and extraction with safe organic solvents. However, due to developments in various fields, new alternative methods have emerged, including high-shear mixing, high-pressure homogenization, and microfluidic processing, which have great potential for lycopene extraction. In addition, ultra-fine grinding is a new option that not only improves the extraction rate of lycopene, but is also a good choice for food-grade solvents. In terms of lycopene protection, lycopene delivery systems have become an alternative method to protect and improve the utilization of lycopene in the body. The development of nanoemulsion carriers, nanostructured lipid carriers, hydrogels, and liposomes is a good choice to improve the protection of lycopene.

In addition, the use of industrial yeast as a host cell to produce lycopene is also a brand new idea. Yeast that does not have a lycopene powder synthesis pathway can become a lycopene-producing strain by introducing genes from an external source. This strategy improves the production efficiency of lycopene and reduces production costs. Under the premise of achieving high lycopene yields, scholars can also develop other effective methods to synthesize other high-value carotenoids.

Reference:

[1]SOUKOULIS C, BOHN T. A comprehensive overview on the micro- and nano-technological encapsulation advances for enhancing the chemical stability and bioavailability of carotenoids[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition,2018,58(1):1-36.

[2]PRZYBYLSKA S. Lycopene-a bioactive carotenoid offering multiple health benefits: a review[J]. International Journal of Food Science & Technology,2020,55(1):11-32.

[3]LIANG X P, MA C C, YAN X J, et al. Advances in research on bioactivity, metabolism, stability and delivery systems of lycopene[J]. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2019,93:185-196.

[4]CLINTON S K, EMENHISER C, SCHWARTZ S J, et al. Cis-trans lycopene isomers, carotenoids, and retinolin the human prostate[J]. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention,1996,5(10):823-833.

[5]HONDA M, KAGEYAMA H, HIBINO T, et al. Efficient and environmentally friendly method for carotenoid extraction from Paracoccus carotinifaciens utilizing naturally occurring Z-isomerization-accelerating catalysts[J]. Process Biochemistry,2020,89:146-154.

[6]SHI B, MA T, YE Z L, et al. Systematic metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for lycopene overproduction[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Che- mistry,2019,67(40):11148-11157.

[7]SHARIFFA Y N, TAN T B, ABAS F, et al. Producing a lycopene nanodispersion: the effects of emulsifiers[J]. Food and Bioproducts Processing,2016,98:210-216.

[8]HONEST K N, ZHANG H W, ZHANG L. Lycopene: isomerization effects on bioavailability and bioactivity properties[J]. Food Reviews International,2011,27(3):248- 258.

[9]FENG L R, QIANG W, YU X B, et al. Effects of exogenous lipids and cold acclimation on lycopene production and fatty acid composition in Blakesleatrispora[J] . AMB Express,2019,9(1).

[10]MEHTA B J, CERDAOLMEDO E. Mutants of carotene production in Blakesleatrispora[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology,1995,42(6):836-838.

[11]LI C J, ZHANG N, SONG J, et al. A single desaturase gene from red yeast Sporidiobolus pararoseus is responsible for both four- and five-step dehydrogenation of phytoene[J]. Gene,2016,590(1):169-176.

[12] Sun Ling, Wang Junhua, Jiang Wei, et al. Construction of a high-efficiency synthetic lycopene yeast strain [J]. Chinese Journal of Bioengineering, 2020, 36(7): 1334-1345.

[13]VERWAAL R, WANG J, MEIJNEN J P, et al. High-level production of beta-carotene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by successive transformation with carotenogenic genes from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,2007,73(13):4342-4350.

[14]MA T, SHI B, YE Z L, et al. Lipid engineering combined with systematic metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for high-yield production of lycopene[J] . Metabolic Engineering,2019,52:134-142.

[15]JING Y W, GUO F, ZHANG S J, et al. Recent advances on biological synthesis of lycopene by using industrial yeast[J]. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research,2021, 60(9):3485-3494.

[16]LUO Z S, LIU N, LAZAR Z, et al. Enhancing isoprenoid synthesis in Yarrowialipolytica by expressing the isopentenol utilization pathway and modulating intracellular hydrophobicity[J]. Metabolic Engineering,2020,61:344-351.

[17]BHATAYAA, SCHMIDT-DANNERT C, LEE P C. Meta- bolic engineering of Pichia pastoris X-33 for lycopene production[J]. Process Biochemistry,2009,44(10):1095-1102.

[18]LI X, WANG Z X, ZHANG G L, et al. Improving lycopene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through optimizing pathway and chassis metabolism[J]. Chemical Engineering Science,2019,193:364-369.

[19]HONG J, PARK S H, KIM S, et al. Efficient production of lycopene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by enzyme engineering and increasing membrane flexibility and NAPDH production[J]. Applied Microbiology and Bio- technology,2019,103(1):211-223.

[20]ALSHEHRI WA, GADALLAN O, EDRIS S, et al. Meta- bolic engineering of mep pathway for overproduction of lvcopene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using pESC-LEU and pTEF1/Zeo vectors[J]. Applied Ecology and Environmental Sesearch,2020,18(4):5279-5292.

[21]ZHANG Y, CHIU T Y, ZHANG J T, et al. Systematical engineering of synthetic yeast for enhanced production of lycopene[J]. Bioengineering,2021,8(1):14.

[22]XU X, LIU J, LU Y L, et al. Pathway engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for efficient lycopene production[J]. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering, 2021,44(6):1033-1047.

[23]BIAN Q, ZHOU PP, YAO Z, et al. Heterologous biosynthesis of lutein in S. cerevisiae enabled by temporospatial pathway control[J]. Metabolic Engineering,2021,67:19-28.

[24]SU B L, YANG F, LI A Z, et al. Upstream activation sequence can function as an insulator for chromosomal regulation of heterologous pathways against position effects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology,2022,194(4):1841-1849.

[25]SU B L, LAI P X, YANG F, et al. Engineering a balanced acetyl coenzyme a metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for lycopene production through rational and evolutionary engineering[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2022,70(13):4019-4029.

[26]ARAYA-GARAY J M, FEIJOO-SIOTA L, ROSA-DOS- SANTOS F, et al. Construction of new PichiapastorisX-33 strains for production of lycopene and beta-carotene[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology,2012,93(6):2483-2492.

[27]ZHANG X, WANG D, DUAN Y, et al. Production of lycopene by metabolically engineered Pichiapastoris[J]. Bioscience,Biotechnology, and Biochemistry,2020,84(3):463-470.

[28]LIU D, LIU H, QI H, et al. Constructing yeast chimeric pathways to boost lipophilic terpene synthesis[J]. ACS Synthetic Biology,2019,8(4):724-733.

[29]ZHANG XK, NIE MY, CHEN J, et al. Multicopy integrants of crt genes and co-expression of AMP deaminase improve lycopene production in Yarrowia lipolytica[J]. Journal of Biotechnology,2019,289:46-54.

[30]XIE Y X, CHEN S L, XIONG X C. Metabolic engineering of non-carotenoid-producing yeast Yarrowialipolytica for the biosynthesis of zeaxanthin[J]. Front Microbiol,2021, 12:699235.

[31]LIU X Q, CUI Z Y, SU T Y, et al. Identification of genome integration sites for developing a CRISPR-based gene expression toolkit in Yarrowialipolytica[J]. Microbial Bio- technology,2022,15(8):2223-2234.

[32]MAGNE T M, BARROS A O D S D, FECHINE P B A, et al. Lycopene as a multifunctional platform for the treatment of cancer and inflammation[J] . Revista Brasileira De Farmacognosia-Brazilian Journal of Pharmacognosy,2022, 32(3):321-330.

[33]LIBBY P, BURING J E, BADIMON L, et al. Athero- sclerosis[J]. Nat RevDis Primers,2019,5(1):56.

[34]GALADARI S, RAHMAN A, PALLICHANKANDY S, et al. Reactive oxygen species and cancer paradox: To promote or to suppress?[J]. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2017,104:144-164.

[35]AKTEPE O H, SAHIN T K, GUNER G, et al. Lycopene sensitizes the cervical cancer cells to cisplatin via targeting nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kappaB) pathway[J]. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences,2021,51(1):368-374.

[36]JEONG Y, LIM J W, KIM H. Lycopene inhibits reactive oxygen species-mediated NF-kappaB signaling and induces apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells[J]. Nutrients,2019, 11(4):762.

[37]TODORIC J, ANTONUCCI L, KARIN M. Targeting inflammation in cancer prevention and therapy[J]. Cancer Prevention Research,2016,9(12):895-905.

[38]MEDZHITOV R. Origin and physiological roles of inflam- mation[J]. Nature,2008,454(7203):428-435.

[39]ARULSELVAN P, FARD M T, TAN W S, et al. Role of antioxidants and natural products in inflammation[J]. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity,2016,(13): 5276130.

[40]SINGH N, BABY D, RAJGURU JP, et al. Inflammation and cancer[J]. Annals of African Medicine,2019,18(3):121-126.

[41]WANG J, ZOU Q H, SUO Y, et al. Lycopene ameliorates systemic inflammation-induced synaptic dysfunction via improving insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction in the liver-brain axis[J]. Food & Function,2019,10(4):2125-2137.

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese