What Is the Benefit of Ginger Extract and Its Using in Food Packing?

Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), a perennial herb in the ginger family, is mainly cultivated and used in some Southeast Asian countries. It has a fragrant and spicy taste and can be used as a condiment, spice, dietary supplement, and traditional medicine. Currently, according to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) for 2022, China is one of the world's leading producers of ginger[1]. In its long history of use and consumption, ginger has not only been enjoyed as a delicacy, but also has a variety of pharmacological properties and has been used in food and medicine. For example, ginger can be used as a tea or health drink to prevent colds, vomiting and relieve fatigue[2]. In addition, ginger is an important component of the Ayurvedic preparation “Trikatu”. Trikatu can be used in combination with other drugs to treat asthma, bronchitis, dysentery, fever and intestinal infections [3].

In China, ginger is also widely used as a folk restorative supplement, medicinal food or as a Chinese herbal medicine in traditional Chinese medicine [4]. The 2020 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia includes three products containing ginger: fresh ginger, dried ginger and fried ginger. In summary, ginger is an important crop with economic, ornamental and even edible medicinal value. Its nutrition and value are widely recognized and it is deeply loved by people. It meets consumers' needs for healthy eating, nutrient intake and dietary therapy, and has developed into one of the essential spices and health-promoting vegetables in life. It has great utilization value and development prospects, which has not only attracted the attention of multiple scientific fields, but is also one of the most researched natural sources over the past decade. Figure 1 shows the continued efforts of the research community, as evidenced by the number of publications on this natural source. This natural product has been vigorously explored in recent years, which may be related to the growth of the dietary supplement and nutraceutical markets due to the coronavirus epidemic.

With the rapid development of the ginger industry and science and technology, people have conducted in-depth research on the nutritional composition and functional value of ginger, which further confirms that ginger has high medicinal value and health care functions. Ginger has been extracted by various methods to discover more of its biological activities, in order to promote the comprehensive utilization and deep processing of ginger. To date, a variety of important bioactive components have been extracted from ginger, such as polysaccharides, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, etc. [1,5], and it has been found that these compounds have antioxidant [6], antibacterial [7], anti-inflammatory [8], anticancer [9], and hypoglycemic [10] effects. Figure 2 summarizes the important active substances in ginger and their biological activities. Many techniques such as ultrasonic-assisted extraction, organic solvent separation, and high-performance liquid chromatography detection have been used to extract, process, separate, and analyze these ginger active ingredients to gain a deeper understanding of their activities. Many ginger products have been developed based on these activities, and these products involve the fields of food, pharmaceuticals, or cosmetics.

In recent years, the use of plant resources to create sustainable, green, non-toxic natural polymers has attracted considerable attention in order to reduce the generation and accumulation of agricultural waste and non-degradable synthetic materials. At present, many plant active substances have been widely used in food packaging materials. These active substances generally have antioxidant and antibacterial effects, which can improve the safety and extend the shelf life of packaged foods [11]. Ginger, as a natural crop, can be used as a sustainable and environmentally friendly material. Its extract, combined with other natural polymers, can improve the mechanical and oxygen barrier properties of the packaging [12]. Its excellent antibacterial and antioxidant properties make it one of the best candidates for food packaging applications. This paper mainly summarizes and discusses the types and biological activities of ginger extracts, as well as the research progress of ginger active substances in food packaging applications. It clarifies the main active ingredients and research hotspots of ginger as a medicinal and edible plant, and provides guidance and theoretical support for the comprehensive utilization and deep processing of ginger, with a view to providing the necessary theoretical knowledge base for in-depth research and development of ginger products and tapping the potential of disease prevention, and improving its bioavailability.

1 Types and biological activities of ginger extracts

Ginger contains many chemical components, including polysaccharides, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, etc., which give ginger a variety of biological activities, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and anticancer, as well as other protective effects, which are beneficial to health. However, the quantity and quality of these bioactive compounds largely depend on the extraction technology, which not only promotes the development of future technology to more effectively extract the active ingredients in ginger, but also maximizes the biological activity of ginger. The specific active ingredients in ginger and their biological activities are summarized in Table 1.

1.1 Types of ginger extract

1. 1. 1 Polysaccharides

Plant-derived polysaccharides are widely attractive in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries due to their multiple health benefits, such as antioxidant [13], anti-tumor [14], anti-influenza [15], hypoglycemic [16], and immunomodulatory [17] effects. Among them, ginger polysaccharides have attracted widespread attention in the biological and medical fields in recent years due to their rich biological properties and pharmacological effects.

The structure of ginger polysaccharides is very complex, and its structural characteristics mainly include the composition and sequence of monosaccharides, molecular weight, and the position and conformation of glycosidic bonds. Polysaccharides are polymers of monosaccharides linked by glycosidic bonds. Most polysaccharides are composed of galactose, glucose, mannose, arabinose, rhamnose, and xylose. In addition, uronic acids, including glucuronic acid and galacturonic acid, are detected in some polysaccharides. The diversity of the monosaccharide composition and molar ratio of these polysaccharides is affected by many factors, such as raw materials, extraction methods, and separation and purification methods [18,19]. There are many methods for analyzing the structure of polysaccharides, including not only instrumental analysis methods such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), infrared spectroscopy (IR), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), gas chromatography (GC), mass spectrometry (MS), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), etc., as well as chemical methods such as methylation analysis, acid hydrolysis, and periodate oxidation, and biological methods such as specific glycosidase digestion and immunological methods.

The chemical structure of polysaccharides is the basis of their biological activity. Many studies have shown that the molecular weight of polysaccharides is closely related to a variety of biological activities, and that an appropriate molecular weight is one of the necessary conditions for polysaccharides to exhibit pharmacological activity. Chen et al. used two different methods to extract polysaccharides from ginger residues and determined that they had different molecular weights, which in turn exhibited different antioxidant activities [19]. In addition, the monosaccharide composition of plant polysaccharides is an important factor affecting their biological activity. Wang et al. used the same extraction method to extract two polysaccharides, GP1 and GP2, from the same raw material. Their monosaccharide compositions are different. GP1 may have anti-tumor activity, while GP2 exhibits antioxidant activity [20]. When the monosaccharide composition is different, even if they have the same pharmacological effect, the strength is also different. Jing et al. showed that the two ginger polysaccharides ZOP and ZOP-1 have significant antioxidant effects, but the antioxidant activity of ZOP-1 is significantly higher than that of ZOP [13]. When the monosaccharide composition is the same, the molar ratio also affects the biological activity of the polysaccharide. Chen et al. confirmed that ginger polysaccharides isolated using hot water extraction and alkali solution extraction, which have different molar ratios of monosaccharide composition, exhibit different antioxidant activities [18].

The effective isolation and purification of ginger polysaccharides is a major prerequisite for studying the structure and biological activity of ginger polysaccharides. In order to maximize the extraction efficiency of biologically active macromolecular polysaccharides from ginger, researchers have conducted a series of studies on purification strategies. At present, there are many methods for isolating and purifying ginger polysaccharides, including hot water extraction, enzyme-assisted extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, and ultrasound-assisted extraction. Each method has its own advantages and disadvantages [18]. With the development of science and technology and the integration of multiple disciplines, research and development of extraction methods with higher extraction rates and that ensure that the biological activity of polysaccharides is not damaged as much as possible is currently a hotspot and focus of research. Although research on ginger polysaccharides has never stopped, further exploration is still needed in terms of purification methods, structure and biological activity. In the future, the structure of ginger polysaccharides can be modified to enhance their inherent biological activity or generate new biological activities. In addition, it is crucial to strengthen research on the structure-activity relationship of modified ginger polysaccharides and clarify the correlation between the structural characterization of modified sites, quantity and activity.

1. 1.2 Terpenes

The smell of ginger is mainly determined by its volatile oil content, also known as terpenes, which consist of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes. The yield varies from 1% to 3% [21] and is the source of the pleasant smell, pungent taste and many pharmacological activities. Monoterpenes have a carbon backbone with two isoprene units (C10 skeleton), and some have one or two cycloalkane units, such as cyclopropane, cyclobutane and cyclohexane. Currently, monoterpenes are found to mainly include the active ingredients eucalyptol, citral, limonene, linalool and pinene. Eucalyptol is a cyclic ether and the main component of Eucalyptus essential oil. It is known to have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anti-hypertensive, antispasmodic, analgesic and anti-anxiety effects [22,23]. Citral is a double bond isomer and a mixture of citronellal and geranial, with the highest content in ginger essential oil [24]. It has a strong lemon aroma. Therefore, citral has been used as a safe flavoring and food additive. It also has liver-protecting and anti-inflammatory effects [25]. Limonene is a cyclic monoterpene that is the main component of citrus peel oil. It is used as an anticancer, antiviral, anti-inflammatory and antibacterial agent [26] and also has the effect of dissolving gallstones and relieving gastroesophageal reflux [27]. Linalool is a terpene alcohol found in plants in the form of two enantiomers and is known to have anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antibacterial, analgesic, anti-anxiety, antidepressant and neuroprotective effects [28].

Pinene is a bicyclic monoterpene that occurs as two isomers (α- and β-) and is used as a flavoring agent. It has gastroprotective, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, neuroprotective, antioxidant, and anti-pancreatitis effects [29]. Sesquiterpenes are characterized by having three isoprene units (C15 skeleton) and are the main components of essential oils in nature. β-elemene is one of the stereoisomers in the elemene group and is found in nature as a component of floral aromas and insect pheromones.

Beta-elemene has been reported to have anticancer effects [30]. Farnesene exists as six isomers and is found in nature as a component of essential oils and pheromones. It is used industrially as a solvent, emollient, vitamin and biofuel [31]. Zeatin is a cyclic sesquiterpene with three double bonds that is highly reactive and used as an anticancer agent [32], antimicrobial agent and fragrance [33].

In summary, these volatile compounds give ginger essential oil its characteristic flavour and aroma as well as its antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Its biological activities are directly related to its chemical composition, which may vary in content and composition depending on the species and be influenced by extraction method, origin, growing conditions, harvest time and other factors. In recent years, attention has been paid to the use of ginger essential oil in food preservation, and its potential as a natural and effective food preservative has been understood, which may have a significant impact on food safety and quality.

1. 1.3 Phenolic compounds

Phenolic compounds are non-volatile components and the main bioactive ingredients in ginger. They include gingerols, shogaols, paradols and zingerone, and their conversion is shown in Figure 3. Gingerols are found in the ginger rhizome as a pungent yellow liquid, but can also form low-melting crystalline solids, which contribute to the activation of spice receptors on the tongue. There are six gingerol congeners, which are distinguished by the length of the branched alkyl side chain. 6-Gingerol is the most abundant compound, while 4-, 7-, 8-, 10- and 12-gingerols are less abundant [34]. It is known that gingerols have anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects [35].

Gingerols can be converted to shogaols by dehydration reactions caused by heating, so a large amount of shogaols can be detected in heat-treated ginger, of which 6-gingerol is the most abundant congener in dried ginger. The conversion of shogaol to shogaolide during heat treatment is greatly affected by heating conditions and temperature. Jung et al. found that the content of 6-gingerol produced under moist heat conditions was significantly higher than that produced under dry heat conditions, and that high temperatures could increase the conversion rate of shogaolide by shortening the heat treatment time [36]. Several reports have shown that shogaols have better pharmacological properties than shogaols, especially their neuroprotective, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [37]. Studies have shown that the α, β-unsaturated ketone in 6-gingenol may be the molecular basis for its greater biological activity than 6-gingerol [38]. Paradols are metabolites of the non-irritating biotransformation of shogaols [39] and are known to have anticancer, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective and neuroprotective effects [40]. Shogaol, also known as vanillylacetone, is a product formed when gingerol undergoes an aldol reaction during drying or heat treatment [40]. Shogaol has been reported to have various effects and activities, such as anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic, antidiarrheal, antispasmodic, anticancer, antiemetic, anxiolytic, antithrombotic, radioprotective and antimicrobial biological

activities [41].

In recent years, there has been a sharp increase in demand for high-quality ginger oleoresin extracts containing phenolic compounds such as shogaols and gingerols, which have health benefits. Lower temperatures and shorter exposure times, such as ultrasound-assisted and enzyme-assisted extraction, can obtain high-quality extracts with high 6-gingerol content [42,43]. High-heat treatments, such as microwave-assisted and pressurized liquid extraction, will yield higher 6-gingerol content [44,45]. Meanwhile, supercritical fluid extraction uses non-toxic CO2, which improves the quality and safety of the extract [46]. Although these green extraction technologies have many environmental, economic and social benefits, there are still many challenges to be addressed in the future. Further development of the bioactive compounds in ginger oleoresin extracts as functional ingredients for food, pharmaceutical or cosmeceutical applications is another important area worth exploring.

1.1.4 Diarylheptanoids

In addition to the above-mentioned active ingredients, ginger also contains diarylheptanoids, which consist of two aryl groups connected by a heptane chain and are divided into linear (curcuminoids) and cyclic forms. Curcumin is the main component of ginger, originally isolated from the turmeric in the ginger family, but it is also present as the main component in ginger.

Curcumin has been reported to have antioxidant, anti-ulcer, anti-cancer, cardioprotective, anti-diabetic, anti-malarial, antibacterial and neuroprotective pharmacological effects [47,48,49].

1. 1.5 Other active ingredients

The chemical substance mixture in ginger, such as ginger essential oil, and some non-volatile components are prepared by extracting with solvents such as ethanol and water, or by powdering fresh or dried ginger roots or using them as an infusion. These extracts have anticancer effects in addition to neuroprotective, cardioprotective and hypoglycemic effects [50,51]. In addition, in order to enhance the therapeutic effect of the mixture of ginger components and other chemical substances, drug delivery systems based on nano-capsules, such as liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, nanostructured lipid particles, nanoemulsions and cyclodextrin complexes, have been developed or proposed [52], to help ginger exert its biological activity better in the body and increase its oral bioavailability.

1.2 Biological activity

1.2.1 Antioxidant activity

It is well known that an excess of free radicals such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) is the cause of many chronic diseases, and ginger has high antioxidant activity. Dugasani et al. found that 6-, 8- and 10-gingerols and 6-gingenol all have strong antioxidant activity, with 6-gingerol having the lowest activity and while 10-gingerol had the highest antioxidant activity of all the gingerols [53]. Ji et al. demonstrated the potential of ginger oleoresin as an effective antioxidant and radiation protectant [54]. In addition, ginger extract can reduce the production of ROS and lipid peroxidation by stimulating the expression of several antioxidant enzymes, thereby exhibiting antioxidant effects [55]. Ginger extract also has a protective and antioxidant effect against cadmium-induced nephrotoxicity [56] and antioxidant protection against lead acetate-induced hepatotoxicity [56]. In addition, the antioxidant capacity of ginger extract is related to the extraction solvent. Yeh et al. compared the antioxidant capacity of ginger ethanol extract and water extract and found that ginger ethanol extract had higher TEAC and FRAP antioxidant activity [58]. In summary, numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that ginger and its bioactive compounds have strong antioxidant activity. The main effect is to balance free radical production, improve the body's defense system, and also play a regulatory role in the antioxidant enzyme or enzyme system.

1.2.2 Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammation can be defined as a protective response of the body that occurs after microbial invasion, antigen exposure, and damage to cells and tissues. It involves a complex interplay between many cell types, mediators, receptors and signal pathways. Studies have shown that NF-κB plays a key role in neuroinflammation, that activation of PPAR-γ can regulate metabolism and inflammation, and that ginger and its various active compounds have anti-inflammatory activity, as has been known for a long time. Han et al. demonstrated that 6-gingerol exerts an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting the production of LPS-induced inflammatory mediators by activating PPAR-γ, thereby inhibiting LPS-induced NF-κB activation to exert an anti-inflammatory effect [59]. Zhang et al. found that 6-gingenol-loaded nanoparticles can alleviate the symptoms of sodium dextran sulfate-induced colitis and accelerate colitis wound repair by regulating the expression levels of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors [60].

Several studies have shown that 6-gingerol also has anti-inflammatory activity. Saha et al. demonstrated that 6-gingerol exerts anti-inflammatory activity by regulating the NF-κB pathway and reducing the protein and mRNA levels of IL-8, IL-6, and IL-1β in inflammation induced by Vibrio cholerae in intestinal epithelial cells [61]. Other active ingredients in ginger have also been shown to have anti-inflammatory activity. For example, ginger extract and gingerol improved trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced colitis by regulating the NF-κB and interleukin-1β pathways [62]. Ginger can also prevent anti-CD3 antibody-induced colitis by reducing TNF-α production and Akt and NF-κB activation [63]. And Teng et al. found that ginger exosome nanoparticles' microRNA improves mouse colitis by inducing IL-22 (a barrier function improvement factor) production [64]. In summary, ginger and its active compounds have been shown to effectively relieve inflammation, especially in inflammatory diseases of the gut. The anti-inflammatory mechanism of ginger may be related to inhibiting Akt and NF-κB activation, enhancing anti-inflammatory cytokines, and reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines. It should be noted that the application of ginger nanoparticles is of great help in improving inflammatory diseases in the gut, including corresponding prevention and treatment.

1.2.3 Neuroprotection

Some people, especially the elderly, are at high risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD) and dementia, and the prevalence of these diseases increases with age. Many studies have shown that ginger may have a positive effect on memory function and a neuroprotective effect against these chronic, incurable diseases, and may even help in the treatment and prevention of neurodegenerative diseases. In Alzheimer's disease, Zeng et al. reported that high-dose ginger extract can improve learning and memory [65]. Karam et al. demonstrated the neuroprotective and therapeutic capacity of ginger by showing that ginger-treated AD rats exhibited significantly increased acetylcholine levels, reduced acetylcholinesterase activity, and the disappearance of amyloid plaques [55]. In Parkinson's disease, Moon et al. found that the active compounds in ginger can reduce the cognitive dysfunction of PD by inhibiting the inflammatory response, increasing NGF levels, and improving synaptic formation in the AD brain [66]. P

Ark et al. reported that 6-gingerol can improve motor coordination disorders and motor retardation in PD, exerting a neuroprotective effect [67]. In addition, Ho et al. found that 10-gingerol in fresh ginger has strong anti-neuroinflammatory properties. It inhibits the expression of pro-inflammatory genes by blocking NF-κB activation, resulting in decreased levels of NO, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α [68]. Another study found that 6-dehydrogingerol has a cytoprotective effect against oxidative stress-induced neuronal cell damage [69]. In addition, the TRV1 receptor has been found in the peripheral and central nervous systems and plays an important role in pain transmission and regulation. It has been reported that ginger has been shown to be active in the TRV1 receptor [70]. The above studies have found that ginger and its bioactive compounds exhibit protective effects against neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and PD.

1.2.4 Antibacterial activity

The spread of bacteria and fungi has always been a serious problem that plagues people's health. The prolonged use of antimicrobials has led to bacterial resistance, and the formation of biofilms is an important cause of bacterial infection and antimicrobial resistance. To address this problem, several herbs and spices have been developed into natural and effective antimicrobial agents against many pathogenic microorganisms. In recent years, ginger has been reported to have antimicrobial activity. One study found that ginger inhibited the growth of various drug-resistant strains, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, by affecting membrane integrity and inhibiting biofilm formation [71].

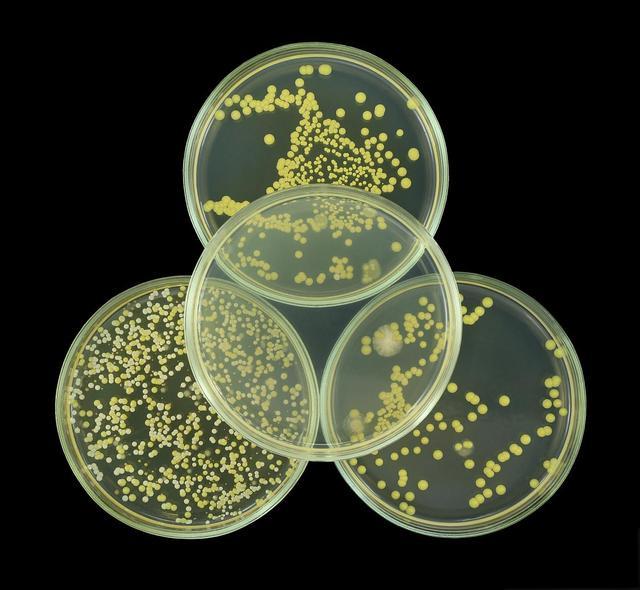

A crude extract and a methanol fraction of ginger inhibited biofilm formation, glucan synthesis, and adhesion of Streptococcus mutans by downregulating virulence genes [72]. Other research results have shown that ginger essential oil has antibacterial properties. Wang et al. demonstrated that ginger essential oil has excellent antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, with the former being more sensitive to ginger essential oil than the latter. The antibacterial mechanism is that ginger essential oil causes damage to the bacterial cell membrane, leakage of macromolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids, and ultimately leads to a decrease in bacterial metabolic activity and death [73]. In summary, ginger has been shown to inhibit the growth of different bacteria and fungi.

1.2.5 Anti-cancer activity

Cancer is a leading cause of death, and some natural products such as fruits and plants have been widely studied for their anti-cancer activity. A large number of in vitro and in vivo studies on ginger extracts have shown that ginger and its active ingredients can eliminate or inhibit the development of different types of cancer. It has been found that ginger extract supplementation can reduce colon mucosal proliferation and promote apoptosis in patients at high risk of colorectal cancer [6]. 6-gingerol, 10-gingerol, 6-shogaol and 10-shogaol have an anti-proliferative effect on human prostate cancer cells by down-regulating the expression of various drug-resistant related proteins [74], have an antiproliferative effect on human prostate cancer cells by downregulating the expression of various drug-resistance-related proteins [74].

6-Gingerol can also inhibit the growth of human cervical adenocarcinoma cells [75]. Ginger extract can also prevent breast cancer by increasing the expression of the tumour suppressor gene p53 and reducing the level of NF-κB in tumour tissue to promote apoptosis [76]. Fluorescent carbon nanodots prepared from ginger can effectively control the growth of tumours caused by human liver cancer cells in nude mice. An in vitro experiment found that ginger carbon nanodots increased the ROS content in liver cancer cells, thereby upregulating p53 expression and promoting apoptosis [77]. Ginger extract and 6-gingenol inhibited the growth of human pancreatic cancer cells without serious adverse reactions [78]. In summary, ginger can prevent and treat several types of cancer, such as colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, cervical cancer, liver cancer and pancreatic cancer. The anti-cancer mechanism is mainly related to inducing apoptosis and inhibiting cancer cell proliferation.

1.2.6 Hypoglycemic activity

Diabetes is a serious metabolic disorder caused by insulin deficiency or insulin resistance, resulting in abnormally elevated blood glucose. Many studies have evaluated the anti-diabetic effects of ginger and its main active ingredients. Sampath et al. found that 6-gingerol can reduce plasma glucose and insulin levels in obese mice caused by a high-fat diet [79]. Wei et al. found that 6-paradol and 6-gingenol promote glucose utilization by increasing AMPK phosphorylation. In addition, 6-Paradol significantly reduced blood glucose levels [7]. Li et al. found that ginger extract can improve insulin sensitivity in rats with metabolic syndrome, which may be related to the improvement of energy metabolism by 6-gingerol [80]. Dongare found that ginger extract can reduce the changes in retinal microvascular in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [81]. In summary, these studies suggest that ginger and its bioactive compounds may prevent and treat diabetes and its complications by lowering insulin levels and increasing insulin sensitivity.

1.2.7 Other biological activities

In addition to the above-mentioned activities, ginger also has protective effects on the respiratory system and anti-nausea, antiemetic, and cardiovascular protective effects. Natural herbs have a long history of use in the treatment of respiratory diseases such as asthma, and ginger is one of these treatments. In some studies, ginger and its bioactive compounds have shown protective effects against respiratory diseases. For example, 6-gingerene, 8-gingerol, and 6-gingerol can induce rapid relaxation of human airway smooth muscle [82]. In addition, ginger can improve allergic asthma [83]. Ginger has traditionally been used to treat gastrointestinal symptoms. Previous research has shown that ginger can reduce vomiting, motion sickness and nausea caused by pregnancy, while recent studies have focused on ginger's preventive effect on postoperative and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial showed that ginger supplementation improved the quality of life associated with nausea in patients after chemotherapy [84]. In addition, ginger can relieve nausea caused by anti-tuberculosis drugs and antiretroviral therapy, and reduce the frequency of mild, moderate and severe nausea attacks in patients [85]. In general, ginger exhibits cardiovascular protective effects by reducing hypertension and improving dyslipidemia. Studies have shown that ginger extract has a vasoprotective effect on porcine coronary arteries by inhibiting NO synthase and cyclooxygenase [86].

2 Application of ginger extract on food packaging

Food is susceptible to various environmental factors, such as moisture, light, oxygen and microorganisms, which may cause food to deteriorate [87]. In addition, food safety issues caused by residues of pesticides, heavy metals and microbial toxins can directly affect the health of consumers [88]. Foodborne pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes and Campylobacter jejuni can even cause human diseases such as gastrointestinal and neurological diseases [89]. Food packaging is an important part of food science and technology. Its main function is to protect its contents from spoilage caused by microorganisms and other organisms, ensure the quality and safety of the product and extend the shelf life. It not only contributes to a sustainable food value chain and reduction of food waste, but also allows consumers to eat safe and hygienic food.

In addition, it can also display product information to help with product commercialization and distribution. Packaging materials are diverse, ranging from single paper packaging to metal, glass and plastic, depending on the individual differences of each product. However, this traditional packaging method generates most of the solid waste, polluting the environment. The materials used are not biodegradable, not only damaging the environment, but also potentially affecting human health by spreading pollution through water, soil and air. To date, the production and use of such non-biodegradable materials as food packaging materials has increased significantly, causing more and more harm to nature. In recent years, with the improvement of people's living standards, there have been increasingly high demands on the quality and safety of food. People have become aware of the importance of food packaging in food protection and are gradually becoming aware of the importance of the natural ecology and their own health. In order to meet the growing demand for environmental sustainability and safety, more and more research has been directed towards the development of food packaging materials that can degrade rapidly in the environment [90].

Biopolymers are chain-like molecular polymers composed of monomer units linked by covalent bonds. They have the ability to degrade or disintegrate through the action of natural organisms, leaving behind environmentally safe organic by-products such as CO2 and H2O. Because of their abundance, renewability and biodegradability, they are considered to be an alternative to non-biodegradable materials such as those made from petroleum [91]. In the past, the most common types of biopolymers used in food packaging applications were natural products such as carbohydrates (starch, cellulose, chitosan, agar), proteins (gelatin, whey protein, collagen), etc.

Today, scientific and technological developments have led to the formation of synthetic biopolymers, including polylactic acid (PLA), polycaprolactone (PCL), polyglycolic acid (PGA), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polybutylene succinate (PBS) [92]. The advantages of these synthetic biopolymers include the potential to create sustainable industries and enhanced properties such as durability, flexibility, high gloss, transparency and tensile strength. Biopolymers can be divided into four categories according to their sources, including natural biopolymers derived from natural organisms (e.g., agricultural resources), synthetic biopolymers produced or fermented from microorganisms (e.g., polyhydroxyalkanoates PHA), biopolymers conventionally synthesized from biological substances (e.g., polylactic acid PLA), and biopolymers chemically synthesized from petroleum products (e.g., polycaprolactone PCL) [93]. As shown in Figure 4, the biopolymers used in food packaging and their classifications are summarized.

However, compared with conventional non-biodegradable materials (especially packaging materials made from petroleum), the use of biopolymers as food packaging materials has poor mechanical properties (e.g., low tensile strength) and barrier properties (e.g., high water permeability). Furthermore, biopolymers are generally brittle, have low heat distortion temperatures, and have low tolerance for prolonged processing operations [94]. However, in order to balance the advantages of using biopolymers as packaging materials, and in particular to meet society's needs for sustainability and environmental safety, many studies have begun to improve these biopolymers for food packaging applications. For example, biobased nanocomposites have been identified as a promising packaging material to improve the mechanical and barrier properties of biopolymers, or the addition of some natural plant, animal or microbial-based biopolymers at the same time, providing a transition for food packaging that is sustainable, biodegradable and improves its performance [95]. Their natural antibacterial and antioxidant properties are used to improve the safety of packaged foods and extend their shelf life.

Ginger has excellent antibacterial and antioxidant properties. Some scholars have studied its application in food packaging by extracting active ingredients from ginger, as shown in Table 2. Saedi et al. successfully prepared transparent and flexible regenerated cellulose films using regenerated cellulose from ginger pulp. The incorporation of curcumin into the regenerated cellulose film provided a strong UV barrier as well as antioxidant and antibacterial activities against a wide range of foodborne pathogens while maintaining transparency, which was proven to be suitable for food packaging applications [96].

Rahmasari et al. found that ginger starch-based edible films treated with ultrasound had better mechanical, barrier, thermal and antibacterial properties, effectively inhibiting lipid oxidation in ground beef samples without negatively affecting the sensory properties of the ground beef [97]. Fasihi et al. found that a biocomposite film loaded with ginger essential oil exhibited excellent UV and light barrier properties, as well as high antioxidant and antibacterial activity, which could be used in bread packaging applications [12]. The addition of ginger glycerin extract to an edible coating formulation has been shown to effectively reduce the growth of Aspergillus flavus can significantly reduce walnut oxidation, thereby improving the nutritional and microbiological quality of nuts as well as their safety and shelf life [98]. Zhang et al. incorporated ginger essential oil into a microemulsion nanofilm, which not only changed the mechanical and water vapor permeability properties of the film, but also improved its resistance to pathogenic bacteria, spoilage bacteria, and inhibition of lipid oxidation, helping to extend the shelf life of fresh meat [99].

In summary, ginger can be delivered in the form of nanoemulsions or solid particles. In addition to being directly used for food preservation, it can also be used to produce biodegradable packaging films or coatings, thereby improving its bioavailability and food preservation efficiency. In addition, the delivery system protects ginger from the environment, providing good controlled-release properties and higher resistance and antioxidant properties for food preservation, showing excellent preservation capabilities for foods such as bread, poultry, fruits and vegetables, and seafood products. The emergence of these sustainable and biodegradable materials has significantly improved the mechanical and barrier properties of packaging, effectively extending shelf life, improving food quality, enhancing food safety and providing consumers with fresher, more sustainable products. With the rapid growth of these materials in the market, they have a promising future. Continued research and development in this field is expected to produce innovative, environmentally friendly packaging solutions, marking a key step towards a more sustainable future for food packaging.

3 Conclusion

The components in ginger, such as shogaol, gingerol and zingerone, have been identified and are recognized as the main compounds contained in ginger extract, giving ginger a variety of biological activities such as anti-oxidation, anti-inflammation and anti-bacterial. Therefore, ginger can be used as an ingredient in functional foods or nutritional products, and can also be used to manage and prevent various diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, neurodegenerative diseases, nausea, vomiting and respiratory diseases. The specific mechanism of action is worth further exploration. The isolation and purification of these ginger bioactive substances remains a challenge. In the future, further research will be conducted on their in vivo mechanisms of action in order to better achieve the diversified utilization of ginger and provide a reference and direction for its development. It is worth noting that clinical trials of ginger and its various bioactive compounds are necessary to demonstrate their efficacy in humans for these diseases. Although ginger resources have been gradually developed and utilized, most of them have been developed and utilized separately, and there is a lack of comprehensive and centralized utilization of ginger after harvesting and processing. Previous studies have shown that the ginger stems, leaves and ginger residues are also rich in active ingredients and have certain medicinal value and development potential. By analyzing the composition, function and application space of ginger by-products, the secondary and multiple utilization of ginger by-products can be used to form a series of large-scale product development and utilization methods, which can not only achieve efficient use of resources and improve economic efficiency, but also protect the environment. This in-depth systematic study of ginger can help people understand and apply ginger from more perspectives.

Research on the application of ginger in food packaging has shown that food packaging materials containing ginger active ingredients have high antibacterial and antioxidant properties. However, packaging films or coatings containing ginger ingredients can change the sensory properties of food, which may have a negative impact. Utilization can be improved and sensory changes in food can be reduced by exploiting the synergistic interactions between ginger or its major components, or by combining them with polymers with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. Alternatively, selecting foods with flavours and aromas that complement those of ginger may reduce the negative impact on sensory attributes. Therefore, further research is needed to improve functionalized food preservation delivery systems containing ginger active ingredients to meet the requirements of various foods and mass-produced products, such as improving utilization, controlling and extending shelf life, while considering cost investment and consumer acceptance. Nowadays, most research is limited to laboratory testing and has not been carried out on a commercial scale. Therefore, the feasibility and commercialization of biodegradable packaging systems containing ginger active ingredients remains to be further explored.

Reference:

[1] KIYAMA R. Nutritional implications of ginger: Chemistry, biological activities and signaling pathways[J]. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2020, 86: 108486.

[2] CRICHTON M, DAVIDSONAR, INNERARITY C, et al. Orally consumed ginger and human health: An umbrella review[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2022, 115(6): 1511-1527.

[3] KUMAR K M, ASISH G, SABU M, et al. Significance of gingers (Zingiberaceae) in Indian System of Medicine-Ayurveda: An overview[J]. Ancient Science of Life, 2013, 32(4): 253-261.

[4] LIH, LIU Y, LUO D, et al. Ginger for health care: An overview of systematic reviews[J]. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 2019, 45: 114-123.

[5] HU W, YU A, WANG S, et al. Extraction, Purification, Structural Characteristics, Biological Activities, and Applications of the Polysaccharides from Zingiber officinale Roscoe. (Ginger): A Review[J]. Molecules, 2023, 28(9): 3855.

[6] NILE S H, PARK S W. Chromatographic analysis, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and xanthine oxidase inhibitory activities of ginger extracts and its

reference compounds[J]. Industrial Crops and Products, 2015, 70: 238-244.

[7] KUMAR N V, MURTHY P S, MANJUNATHA J R, et al. Synthesis and quorum sensing inhibitory activity of key phenolic compounds of ginger and their derivatives[J]. Food Chemistry, 2014, 159: 451-457.

[8] ZHANG M, VIENNOIS E, PRASAD M, et al. Edible ginger-derived nanoparticles: A novel therapeutic approach for the prevention and treatment of

inflammatory bowel disease and colitis-associated cancer[J]. Biomaterials, 2016, 101: 321-340.

[9] CITRONBERG J, BOSTICK R, AHEARN T, et al. Effects of ginger supplementation on cell-cycle biomarkers in the normal-appearing colonic mucosa of patients at increased risk for colorectal cancer: Results from a pilot, randomized, and controlled trial[J]. Cancer Prevention Research, 2013, 6(4): 271-281.

[10] WEI C, TSAI Y, KORINEK M , et al. 6-Paradol and 6-shogaol, the pungent compounds of ginger, promote glucose utilization in adipocytes and myotubes,and 6-paradol reduces blood glucose in high-fat diet-fed mice[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2017, 18(1): 168.

[11] LEE JY, GARCIA C V, SHIN G H, et al. Antibacterial and antioxidant properties of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose-based active composite films incorporating oregano essential oil nanoemulsions[J]. LWT, 106 (2019): 164-171.

[12] FASIHI H, NOSHIRVANI N, HASHEMI M. Novel bioactive films integrated with Pickering emulsion of ginger essential oil for food packaging application[J]. Food Bioscience, 2023, 51: 102269.

[13] JINGY, CHENG W, MAY, et al. Structural Characterization, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of a Novel Polysaccharide from Zingiber officinale and Its Application in Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles[J]. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2022, 9: 917094.

[14] LIAO D, CHENG C, LIU J, et al. Characterization and antitumor activities of polysaccharides obtained from ginger (Zingiber officinale) by different extraction methods[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 152: 894-903.

[15] HU H, HU M, WANG D, et al. Mixed polysaccharides derived from Shiitake mushroom, Poriacocos, Ginger, and Tangerine peel enhanced protective

immune responses in mice induced by inactivated influenza vaccine[J]. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy, 2020, 126: 110049.

[16] CARVALHO GCN, LIRA-NETO JCG, ARAÚJO MFM, et al. Effectiveness of ginger in reducing metabolic levels in people with diabetes: a randomized clinical trial[J]. Revista Latino-americana De Enfermagem, 2020, 28: e3369.

[17] [17] LIU J, WANG J, ZHOU S, et al. Ginger polysaccharides enhance intestinal immunity by modulating gut microbiota in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2022, 223: 1308-1319.

[18] CHEN X, CHEN G, WANG Z, et al. A comparison of a polysaccharide extracted from ginger (Zingiber officinale) stems and leaves using different methods: Preparation, structure characteristics, and biological activities[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 151: 635-649.

[19] CHEN G, YUAN B, WANG H, et al. Characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides obtained from ginger pomace using two different extraction processes[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2019, 139: 801-809.

[20] WANG Y, WEI X, WANG F, et al. Structural characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from ginger[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2018, 111: 862-869.

[21] BADRELDIN H, BLUNDEN G, MUSBAH O, et al. Some phytochemical,pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): a review of recent research[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2008, 46 (2): 409-420.

[22] JUERGENS U. Anti-inflammatory properties of the monoterpene 1.8-cineole: current evidence for co-medication in inflammatory airway diseases[J]. Drug Research, 2014, 64 (12): 638-646.

[23] SEOL G, KIM K. Eucalyptol and its role in chronic diseases[J]. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 2016, 929: 389-398.

[24] STAPPEN I, HOELZL A, RANDJELOVIC O, et al. Influence of essential ginger oil on human psychophysiology after inhalation and dermal application[J]. Natural Product Communications, 2016, 11(10): 1569-1578.

[25] LAIY, LEE W, LINY, et al. Ginger essential oil ameliorates hepatic injury and lipid accumulation in high fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2016, 64 (10): 2062-2071.

[26] MUKHTAR Y, MICHAEL A, XU X, et al. Biochemical significance of limonene and its metabolites: future prospects for designing and developing highly potent anticancer drugs[J]. Bioscience Reports, 2018, 38 (6): BSR20181253

[27] SUN J. D-limonene: safety and clinical applications[J]. Alternative Medicine Review: A journal of Clinical Therapeutic, 2017, 12 (3): 259-264

[28] PEREIRA I, SEVERINO P, SANTOS A, et al. Linalool bioactive properties and potential applicability in drug delivery systems[J]. Colloids and Surfaces.B, Biointerfaces, 2018, 171: 566-578.

[29] ZHAIB, ZENG Y, ZENG Z, et al. Drug delivery systems for elemene, its main active ingredient β-elemene, and its derivatives in cancer therapy[J].International Journal of Nanomedicine, 2018, 13: 6279-6296.

[30] ZHAIB, ZHANG N, HAN X, et al. Molecular targets of β-elemene, a herbal extract used in traditional Chinese medicine, and its potential role in cancertherapy: a review[J]. Biomed and Pharmacother, 2019, 114: 108812.

[31] GEORGE K, ALONSO-GUTIERREZ J, KEASLING J, et al. Isoprenoid drugs, biofuels, and chemicals--artemisinin, farnesene, and beyond[J].Biotechnology of Isoprenoids, 2015, 148: 355-389.

[32] GIRISA S, SHABNAM B, MONISHAJ, et al. Potential of zerumbone as an anti-cancer agent[J]. Molecules, 2019, 24 (4): 734.

[33] KITAYAMAT. Attractive reactivity of a natural product, zerumbone[J]. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 2011,75(2): 199-207. DOI: 10.1271/bbb.100532

[34] VARAKUMAR S, UMESH K, SINGHALR. Enhanced extraction of oleoresin from ginger (Zingiber officinale) rhizome powder using enzyme-assisted three phase partitioning[J]. Food Chemistry, 2017, 216: 27-36.

[35] WANG S, ZHANG C, YANG G, et al. Biological properties of 6-gingerol: abrief review[J]. Natural Product Communications, 2014, 9 (7):1027-1030

[36] JUNG MY, LEE M K, PARK H J, et al. Heat-induced conversion of gingerolsto shogaols in ginger as affected by heat type (dry or moist heat), sample

type (fresh or dried), temperature and time[J]. Food Science and Biotechnology, 2018, 27 (3): 687-693. DOI: 10.1007/s10068-017-0301-1

[37] OHNISHI M, OHSHITAM, TAMAKIH, et al. Shogaol but not gingerolhas a neuroprotective effect on hemorrhagic brain injury: Contribution of the α β-unsaturated carbonyl to heme oxygenase-1 expression[J]. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2019, 842: 33-39.

[38] KOU X, WANG X, JI R, et al. Occurrence, biological activity and metabolism of 6-shogaol[J]. Food and Function, 2018, 9(3) :1310-1327.

[39] SAPKOTA A, PARK S J, CHOI J W. Neuroprotective Effects of 6-Shogaol and Its Metabolite, 6-Paradol, in a Mouse Model of Multiple Sclerosis[J].

Biomolecules and Therapeutics, 2019, 27 (2): 152-159. DOI: 10.4062/biomolther.2018.089

[40] JIN G, SUNY, MINSUN J, et al. Pharmacotherapeutic potential of ginger and its compounds in age-related neurological disorders[J]. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 2018, 182: 56-69. DOI: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.08.010

[41] AHMAD B, REHMAN M, AMIN I, et al. A review on pharmacological properties of zingerone (4-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2-butanone) [J]. The Scientific World Journal, 2015, 2015: 816364. DOI: 10.1155/2015/816364

[42] KOU X, LIX, RAHMAN M RT, et al. Efficient dehydration of 6-gingerol to 6-shogaol catalyzed by an acidic ionic liquid under ultrasound irradiation[J]. Food Chemistry, 2017, 215: 193-199. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.106

[43] BANERJEE J, SINGH R, VIJAYARAGHAVAN R, et al. Bioactives from fruit processing wastes: Green approaches to valuable chemicals[J]. Food Chemistry, 2017, 225: 10-22. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.12.093

[44] NIRAMON U, SIRINAPA SI, PHENPHICHAR W, et al. Development of edible Thai rice film fortified with ginger extract using microwave-assisted extraction for oral antimicrobial properties[J]. Scientific Reports, 2021, 11 (1): 1-10. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-94430-y

[45] SARIP M, MORADN, MOHAMAD N, et al. The kinetics of extraction of the medicinal ginger bioactive compounds using hot compressed water[J]. Separation and Purification Technology, 2014, 124: 141-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2014.01.008

[46] LOURDES V, ALICIA O, GUILLERMO C, et al. Valorization of cacao pod husk through supercritical fluid extraction of phenolic compounds[J]. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 2018, 131: 99-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2017.09.011

[47] QADIR M, NAQVI ST, MUHAMMAD SA. Curcumin: a polyphenol with molecular targets for cancer control[J]. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 2016, 17 (6): 2735-2739.

[48] KOCAADAM B, ŞANLIER N. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric (Curcuma longa), and its effects on health[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2017, 57 (13) :2889-2895. DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1077195

[49] AKBAR M U, REHMAN K, ZIA K M, et al. Critical review on curcumin as a therapeutic agent: from traditional herbal medicine to an ideal therapeutic agent[J]. Critical Reviews in Eukaryotic Gene Expression, 2018, 28 (1): 17-24. DOI: 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2018020088

[50] SHUKLA Y, SINGH M. Cancer preventive properties of ginger: abrief review[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2017, 45 (5): 683-690. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.11.002

[51] DE LIMAR M T, DOS REIS AC, DE MENEZES A P M, et al. Protective and therapeutic potential of ginger (Zingiber officinale) extract and [6]-gingerol in cancer: a comprehensive review[J]. Phytotherapy Research, 2018, 32(10): 1885-1907. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.6134

[52] MOHD SAHARDI NFN, MAKPOL S. Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) in the prevention of ageing and degenerative diseases: review of current

evidence[J]. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2019, 2019: 5054395. DOI: 10.1155/2019/5054395

[53] DUGASANI S, PICHIKAM R, NADARAJAH V D, et al. Comparative antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of [6]-gingerol, [8]-gingerol, [10]-

gingerol and [6]-shogaol[J]. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2010, 127 (2): 515-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2009.10.004

[54] JI K, FANG L, ZHAO H, et al. Ginger oleoresin alleviated γ-ray irradiation-induced reactive oxygen species via theNrf2 protective response in human

mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2017, 2017: 1480294. DOI: 10.1155/2017/1480294

[55] HOSSEINZADEH A, JUYBARI K B.; FATEMI M J, et al. Protective effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) extract against oxidative stress and

mitochondrial apoptosis induced by interleukin-1 beta in cultured chondrocytes[J]. Cells Tissues Organs, 2017, 204: 241–250. DOI: 10.1159/000479789

[56] GABR SA,ALGHADIRAH, GHONIEM GA. Biological activities of ginger against cadmium-induced renal toxicity[J]. Saudi Journal of Biological

Sciences, 2019, 26(2): 382-389. DOI: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.08.008

[57] MOHAMED O I, EL-NAHASAF, EL-SAYEDY S, ASHRY K M. Ginger extract modulates Pb-induced hepatic oxidative stress and expression of

antioxidant gene transcripts in rat liver[J]. Pharmaceutical Biology, 2016, 54(7): 1164-1172. DOI: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1057651

[58] YEH H, CHUANG C, CHEN H, et al. Bioactive components analysis of two various gingers (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) and antioxidant effect of ginger

extracts[J]. LWT- Food Science and Technology, 2014, 55: 329–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2013.08.003

[59] HAN Q, YUAN Q, MENG X, et al. 6-Shogaol attenuates LPS-induced inflammation in BV2 microglia cells by activating PPAR-γ[J]. Oncotarget. 2017,8(26): 42001-42006.

[60] ZHANG M, XU C, LIU D, et al. Oral delivery of nanoparticles loaded with ginger active compound, 6-shogaol, attenuates ulcerative colitis and promotes

wound healing in a murine model of ulcerative colitis[J]. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, 2018, 12: 217–229.

[61] SAHA P, KATARKARA, DAS B, et al. 6-Gingerol inhibits Vibrio cholerae-induced proinflammatory cytokines in intestinal epithelial cells via modulation

of NF-κB[J]. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2016, 54(9): 1606-1615. DOI: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1110598

[62] HSIANG C, LO H, HUANG H, et al. Ginger extract and zingerone ameliorated trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colitis in mice via modulation of

nuclear factor-κB activity and interleukin-1β signalling pathway[J]. Food Chemistry, 2013, 136:170–177. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.124

[63] UENO N, HASEBE T, KANEKO A, et al. TU-100 (Daikenchuto) and ginger ameliorate anti-CD3 antibody induced T cell-mediated murine enteritis: microbe-independent effects involving Akt and Nf-κB suppression[J]. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9(5), e97456. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097456

[64] TENGY, RENY, SAYED M, et al. Plant-derived exosomal micrornas shape the gut microbiota[J]. Cell Host and Microbe, 2018, 24(5), 637–652. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.10.001

[65] ZENG GF, ZHANG ZY, LU L, et al. Protective effects of ginger root extract on Alzheimer disease-induced behavioral dysfunction in rats[J]. Rejuvenation Research, 2013, 16(2): 124-133. DOI: 10.1089/rej.2012.1389

[66] MOON M, KIM H G, CHOI J G , et al. 6-Shogaol, an active constituent of ginger, attenuates neuroinflammation and cognitive deficits in animal models of dementia[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2014, 449(1): 8-13. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.121

[67] PARK G, KIM HG, JU MS, et al. 6-Shogaol, an active compound of ginger, protects dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson's disease models via anti-

neuroinflammation[J]. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 2013, 34(9): 1131-1139. DOI: 10.1038/aps.2013.57

[68] HO SC, CHANG KS, LIN CC. Anti-neuroinflammatory capacity of fresh ginger is attributed mainly to 10-gingerol[J]. Food Chemistry, 2013, 141(3): 3183-3191. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.010

[69] YAO J, GE C, DUAN D, et al. Activation of the phase II enzymes for neuroprotection by ginger active constituent 6-dehydrogingerdione in PC12 cells[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2014, 62(24): 5507-5518. DOI: 10.1021/jf405553v

[70] DEDOV VN, TRAN V H, DUKE C C, et al. Gingerols: a novel class of vanilloid receptor (VR1) agonists[J]. British Journal of Pharmacology, 2002 ,137

(6): 793-798. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704925.

[71] CHAKOTIYA A S, TANWAR A, NARULA A, et al. Zingiber officinale: Its antibacterial activity on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and mode of action

evaluated by flow cytometry[J]. Microbial Pathogenesis, 2017, 107: 254-260. DOI: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.03.029

[72] HASAN S, DANISHUDDIN M, KHAN AU. Inhibitory effect of Zingiber officinale towards Streptococcus mutans virulence and caries development: in vitro and in vivo studies[J]. BMC Microbiology, 2015 ,15 (1) :1. DOI: 10.1186/s12866-014-0320-5

[73] WANG X, SHENY, THAKUR K, et al. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Ginger Essential Oil against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus[J]. Molecules, 2020, 25(17): 3955. DOI: 10.3390/molecules25173955

[74] LIU C M, KAO C L, TSENG YT, et al. Ginger Phytochemicals Inhibit Cell Growth and Modulate Drug Resistance Factors in Docetaxel Resistant Prostate Cancer Cell[J]. Molecules, 2017, 22(9): 1477.

[75] ZHANG F, ZHANG J G, QU J, et al. Assessment of anti-cancerous potential of 6-gingerol (Tongling White Ginger) and its synergy with drugs on humancervical adenocarcinoma cells[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2017, 109 (Pt 2): 910-922.

[76] EL-ASHMAWY NE, KHEDR NF, EL-BAHRAWY HA, et al. Ginger extract adjuvant to doxorubicin in mammary carcinoma: study of some molecular mechanisms[J]. European Journal of Nutrition, 2018, 57(3): 981-989.

[77] LI C L, OU C M, HUANG C C, et al. Carbon dots prepared from ginger exhibiting efficient inhibition of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells[J]. Journalof Materials Chemistry, B, 2014, 2 (28), 4564–4571.

[78] AKIMOTO M, IIZUKAM, KANEMATSU R, et al. Anticancer effect of ginger extract against pancreatic cancer cells mainly through reactive oxygen

species-mediated autotic cell death[J]. PLoS ONE, 2015, 10(5): e0126605. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126605

[79] SAMPATH C, RASHID M R, SANG S, et al. Specific bioactive compounds in ginger and apple alleviate hyperglycemia in mice with high fat diet-induced

obesity viaNrf2 mediated pathway[J]. Food Chemistry. 2017, 226: 79–88. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.056

[80] LI Y, TRAN V H, KOTA B P, et al. Preventative effect of Zingiber officinale on insulin resistance in a high-fat high-carbohydrate diet-fed rat model and its

mechanism of action[J]. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 2014, 115 (2): 209-215. DOI: 10.1111/bcpt.12196

[81] DONGARE S, GUPTA S K, MATHUR R, et al. Zingiber officinale attenuates retinal microvascular changes in diabetic rats via anti-inflammatory and antiangiogenic mechanisms[J]. Molecular Vision, 2016, 22: 599–609.

[82] TOWNSEND EA, ZHANG Y, XU C, et al. Active components of ginger potentiate β-agonist-induced relaxation of airway smooth muscle by modulating cytoskeletal regulatory proteins[J]. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular biology, 2014, 50(1): 115–124.

[83] KHANAM, SHAHZAD M, RAZA ASIM MB, et al. Zingiber officinale ameliorates allergic asthma via suppression of Th2-mediated immune response[J].Pharmaceutical Biology, 2015, 53(3): 359–367.

[84] [84] EMRANI Z, SHOJAEIE, KHALILI H. Ginger for prevention of antituberculosis-induced gastrointestinal adverse reactions including hepatotoxicity: A

randomized pilot clinical trial[J]. Phytotherapy Research: PTR, 2016, 30(6): 1003–1009. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.5607

[85] PALATTY PL, HANIADKAR, VALDER B. Ginger in the prevention of nausea and vomiting: A review[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2013, 53(7): 659–669.

[86] [86] WU H C, HORNG C T, TSAI SC, et al. Relaxant and vasoprotective effects of ginger extracts on porcine coronary arteries[J]. International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 2018, 41(4): 2420–2428. DOI: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3380

[87] REDFEARN HN, WARREN MK, GODDARD JM. Reactive Extrusion of Nonmigratory Active and Intelligent Packaging[J]. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 2023, 15(24): 29511-29524. DOI: 10.1021/acsami.3c06589

[88] ESMAEILI Y, PAIDARI S, BAGHBADERANI SA, et al. Essential oils as natural antimicrobial agents in postharvest treatments of fruits and vegetables: A review[J]. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 2021, pp. 1-16

[89] LAWALKG, RIAZ A, MOSTAFAH, et al. Development of Carboxymethylcellulose Based Active and Edible Food Packaging Films Using Date Seed Components as Reinforcing Agent: Physical, Biological, and Mechanical Properties[J]. Food Biophysics, 2023, pp. 1-13

[90] JAYARAMUDU J, REDDY GS, VARAPRASAD K, et al. Preparation and properties of biodegradable films from Sterculiaurens short fiber/cellulose green composites[J]. Carbohydr Polym. 2013, 93(2): 622-627.

[91] LIU W, MISRAM, ASKELAND P, et al. ‘Green’ Composites from Soy Based Plastic and Pineapple Leaf Fiber: Fabrication and Properties Evaluation[J]. Polymer, 2005, 46(8): 2710-2721.

[92] SHIV S, RHIM JW. Bio-Nanocomposites for Food Packaging Applications[J]. Encyclopedia of Renewable and Sustainable Materials, 2020, 5: 29-41.

[93] Siti Hajar Othman, Bio-nanocomposite Materials for Food Packaging Applications: Types of Biopolymer and Nano-sized Filler, Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia, 2014, 2: 296-303. [94] SORRENTINOA, GORRASI G, VITTORIA V. Potential Perspectives of Bio-Nanocomposites for Food Packaging Applications[J]. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 2007, 18(2): 84-95. [95] AGATA Z, ANNA S, RAFAËLJ, et al. Bio-based aliphatic/aromatic poly (trimethylene furanoate/sebacate) random copolymers: Correlation between mechanical, gas barrier performances and compostability and copolymer composition[J]. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2022, 195: 109800.

[96] SAEDI S, KIM JUN, LEE E, et al. Fully transparent and flexible antibacterial packaging films based on regenerated cellulose extracted from ginger pulp[J]. Industrial Crops and Products, 2023, 197: 116554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116554

[97] RAHMASARI Y, YEMIŞ GP. Characterization of ginger starch-based edible films incorporated with coconut shell liquid smoke by ultrasound treatment and application for ground beef[J]. Meat Science, 2022, 188: 108799. DOI: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2022.108799

[98] SHAUKAT M, PALMERIR, RESTUCCI C, et al. Glycerol ginger extract addition to edible coating formulation for preventing oxidation and fungal spoilage of stored walnuts[J]. Food Bioscience, 2023. 52:102420.

[99] ZHANG L, LIU A, WANG W, et al. Characterisation of microemulsion nanofilms based on Tilapia fish skin gelatine and ZnO nanoparticles incorporated

with ginger essential oil: Meat packaging application[J]. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 2017, 52 (7): 1670-1679.

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese