Study on the Production Method of Lycopene Powder

Lycopene is an important carotenoid that belongs to the terpene family of tetraterpenoids. It is found in nature mainly in tomatoes, tomato products, and fruits such as watermelons and grapefruits. It is the main pigment in ripe tomatoes. Lycopene is a strong antioxidant with physiological functions such as anti-oxidation, anti-cancer and lowering blood lipids. It is widely used in health foods, medicine, cosmetics and other fields [1-2]. At present, lycopene has been widely used as a nutritional supplement and coloring agent in many countries [3]. The global cumulative sales of lycopene raw materials are increasing year by year, and the market prospects are broad.

Lycopene powder production mainly relies on two methods: plant extraction and chemical synthesis. The plant extraction method is limited by the season, and the long plant growth cycle and low product content cannot ensure intensive and large-scale production of the product. The chemical synthesis method has problems such as chemical reagent residues, multiple isomeric forms, and environmental pollution. The biotechnology synthesis method has the advantages of low cost, short cycle, stable supply, and environmentally friendly and sustainable development. In recent years, it has attracted more and more attention from researchers.

At present, research on the biotechnological synthesis of lycopene powder has made considerable progress, such as the diversification of choices of microbial host cells, research and innovation in metabolic engineering to transform pathways, and exploration of fermentation processes and amplification techniques, which have significantly improved the yield of lycopene synthesized by biotechnology. However, most research is still focused on breakthroughs in a single technical field, and there has been relatively little systematic research and summary of the biotechnological synthesis of lycopene.

Therefore, this paper reviews the physical and chemical properties of lycopene and current production technologies, systematically summarizes research on the biosynthesis of lycopene using biotechnology represented by synthetic biology, focusing on the comparison of fermentation methods of different strains and accurate quantification methods of lycopene, and proposes problems in the production of lycopene using biotechnology and future research directions, with a view to providing a reference for the industrial production of lycopene using biotechnology and the biosynthesis of other high value-added natural products using biotechnology.

1. The physical and chemical properties and applications of lycopene powder

Lycopene is a tetraterpene compound, an unsaturated alkenyl compound, and a carotenoid that does not contain oxygen atoms. Lycopene has the molecular formula C40H56 and a relative molecular mass of 536.85. It has 11 conjugated double bonds and 2 non-conjugated double bonds in its molecular structure, and often exists in cis-trans isomers. In nature, natural lycopene is mainly all-trans, with a very small amount of cis.

Lycopene powder is a fat-soluble pigment that is insoluble in water, but soluble in lipids and non-polar organic solvents. Its molecular structure contains a chromophore, which corresponds to a unique absorption region in the ultraviolet-visible absorption spectrum. The color depth varies from orange-yellow to dark red depending on the concentration of lycopene, and may slightly change with the solvent. For example, lycopene crystals dissolved in sunflower oil appear a visible dark red, while dissolved in petroleum ether appear yellow. Due to the relatively large number of double bonds in the molecule, lycopene is very reactive and prone to oxidation and structural isomerization reactions under light, oxygen, and high temperature conditions, which can lead to a decrease in physiological activity [4]. Therefore, when lycopene is extracted, antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E, 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (BHT), and tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) are often added [5].

Unlike β-carotene, lycopene does not have the pro-active properties of vitamin A, so its application was not valued in the early days. However, in recent years, as the physiological functions of lycopene have gradually become better known, its application has become more widespread. Lycopene is a powerful antioxidant that can scavenge oxygen free radicals in the human body and quench singlet oxygen. Its antioxidant capacity is about 100 times that of vitamin E and twice that of beta-carotene [6-9]. It has also been shown to have anti-tumor, prevent prostate disease and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease [10-11]. It is widely used in cosmetics, health products and food. Lycopene has currently obtained the “novel food” approval of the European Union and the “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) status in the United States. With the improvement of people's living standards and the increasing emphasis on health, the United States predicts that lycopene sales will grow at a rate of 35% per year. Therefore, the efficient biosynthesis technology of lycopene has great market application value.

2 Production method of lycopene powder

2.1 Comparison of lycopene powder production methods

Currently, there are three methods for producing lycopene: plant extraction, chemical synthesis, and biosynthesis. The plant extraction method mainly involves extracting and purifying lycopene from ripe plant fruits such as tomatoes. However, this method is affected by various factors such as region, season, tomato variety, and maturity, and is therefore unstable. In China, lycopene is mainly extracted from tomatoes grown in Xinjiang (with long days of sunshine). However, the lycopene content in tomatoes is very low, generally only 20 mg/kg, and even in the tomato skin, where the content is higher, it is less than 0.4 g/kg [12].

The extraction cost is high, and the extract often contains other carotenoids, which affects the purity of the product. and because the content is low, the extraction process consumes a large amount of organic solvents, which has a greater impact on environmental pollution. The chemical synthesis method mainly involves the Wittig reaction of octatrienedial and triphenylphosphine chloride or triphenylphosphine sulfide to synthesize lycopene [13]. The chemical synthesis method has the characteristics of high yield (more than 65%), cheap and recyclable raw materials, and mild reaction conditions. Although the chemical synthesis method has high yield and low cost, it is prone to isomerism due to the many double bonds in the lycopene structure, and there is a risk to safety as the product may contain solvent residues. The biosynthesis method refers to the process in which microorganisms ferment and produce lycopene using abundant and readily available raw materials such as sugars, corn syrup and inorganic salts. The microbial fermentation method not only has the safety of the plant extraction method (both are naturally derived from biological metabolism and are not artificially synthesized), but also has the advantages of low cost and large-scale production of the chemical synthesis method. It is considered to be an ideal method for the future production of lycopene.

2.2 Biosynthetic pathway of lycopene powder

Lycopene is a tetraterpenoid compound similar to other terpenoids. The common precursors for its biosynthesis are the two isopentenyl units IPP (isopentenyl pyrophosphate) and DMAPP (dimethylallyl pyrophosphate), which are isomers of each other [14]. Currently, there are two ways to synthesize IPP and DMAPP in nature: one is the MEP (2-methyl-erythritol-4-phosphate) pathway in prokaryotes and plants, and the other is the MVA (mevalonate) pathway in eukaryotes.

the MEP (2-methyl-erythritol-4-phosphate) pathway in prokaryotes and plants, and the MVA (mevalonate) pathway in eukaryotes.

The MEP pathway uses pyruvate and 3-phosphoglycerate as starting substrates to synthesize IPP and DMAPP [15], while the MVA pathway uses acetyl coenzyme A as the starting substrate to synthesize IPP and DMAPP through a seven-step enzymatic reaction [16]. Compared with the MEP pathway, the MVA pathway was studied earlier and its reaction mechanism is more thorough. The biosynthetic pathway of lycopene can be divided into two modules. The upstream module is the process of synthesizing the precursor substances IPP and DMAPP, and the downstream module is the process of synthesizing lycopene from IPP and DMAPP (see Figure 1 for an overview). IPP and DMAPP undergo stepwise condensation reactions under the action of isopentenyl transferase to generate GGPP, and then GGPP (geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate) is converted to octahydro-lycopene by the action of octahydro-lycopene synthase (phytoene synthase, CrtB), and then to lycopene by the action of octahydro-lycopene dehydrogenase (phytoene desaturase, CrtI).

2.3 Microorganisms that synthesize lycopene

The currently known microorganisms that ferment to produce lycopene include: the pantoea that can synthesize lycopene itself, Blakeslea trispora, and metabolically engineered yeast, Yarrowia lipolytica, and Escherichia coli. Among them, Blakeslea trispora has been studied more [17] and is also the only strain that can achieve industrial production of β-carotene. Lycopene, an intermediate product in the synthesis of β-carotene, can be accumulated by adding a lycopene cyclase inhibitor during the fermentation process. Several studies have shown that the production of lycopene by Blakeslea trispora has been continuously improved, and the highest reported lycopene production is 3.4 g/L [18]. However, the trichothecene mold is prone to degeneration during subculture, resulting in unstable yields. In addition, the long growth cycle makes it less productive, and the need to add inhibitors during production also greatly limits the process of fermenting lycopene with trichothecene mold [19].

3 Research on the biotechnological synthesis of lycopene

3.1 Engineering modification of the main microorganisms for synthesizing lycopene

Escherichia coli is one of the most commonly used microbial hosts for the heterologous synthesis of terpenoids. Advantages such as a clear genetic background, rapid cell growth, and a wealth of genetic manipulation tools make E. coli an ideal host platform for industrial product development. Some scholars have successfully engineered E. coli for the heterologous production of high-yield carotenoids through metabolic engineering and synthetic biology techniques [20-21]. However, due to the risks of E. coli being susceptible to phage infection and the presence of endotoxins [22], the use of E. coli to produce lycopene currently poses certain food safety risks and its industrial application is therefore limited.

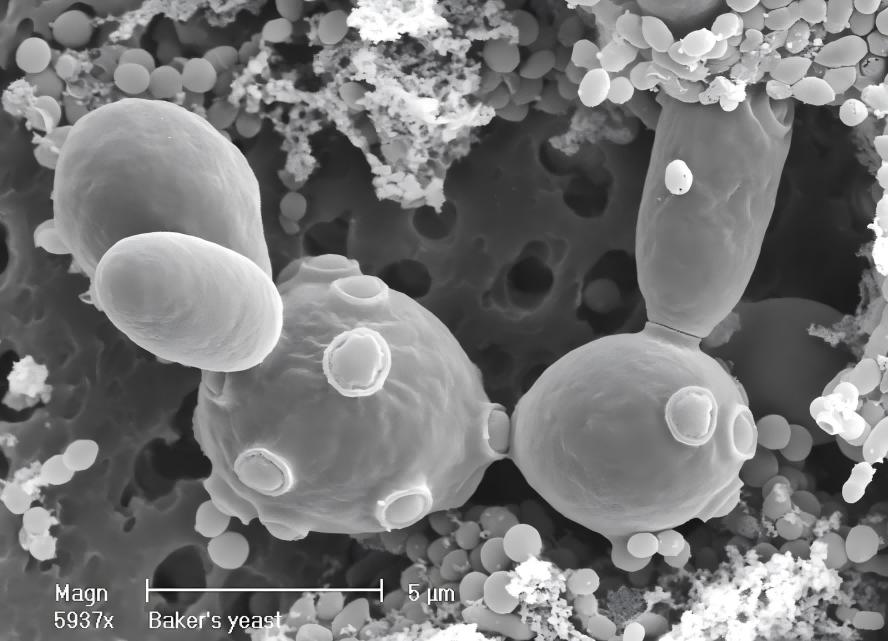

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an eukaryotic model organism whose genome has been sequenced, whose cell biology has been well characterized, and for which there are mature genetic manipulation tools and methods. There is no risk of phage contamination during large-scale fermentation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and it is generally considered safer than Escherichia coli. Therefore, the use of metabolic engineering to transform Saccharomyces cerevisiae for heterologous production of lycopene is considered to have great application prospects. Like Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae cannot synthesize carotenoids on its own and must introduce the relevant synthesis genes [23-26].

Yarrowia lipolytica is an unconventional microbial host that produces large amounts of lipids and is considered safe. Although it cannot directly synthesize carotenoids, it can produce large amounts of the precursor acetyl coenzyme A, and the synthesis of carotenoids can be achieved by introducing exogenous key enzymes. Researchers have developed many genetic tools to engineer Lipomyces yeast, which is considered to be a promising host for the production of carotenoids via the MVA pathway [27-28].

Eukaryotic microalgae, as autotrophic microorganisms, can use light energy and carbon dioxide to produce biomass, and therefore have great metabolic potential for the sustainable production of terpenoids. However, the current research on the metabolic engineering of high-level algae lags far behind that of other hosts, which to some extent limits its application [29].

The red yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides can produce pigments such as β-carotene and γ-carotene through intracellular biosynthesis. Researchers have enhanced its carotenoid production capacity by optimizing the culture conditions and mutagenesis. However, there is currently very limited research on red yeast, possibly due to the limitations of the available genomic data and the lack of functional annotation of key genes, which has largely hindered the metabolic engineering of high-yield carotenoids [30]. Other non-carotenogenic yeasts, such as Pichia pastoris, which can grow at high densities without ethanol accumulation, have also been engineered to synthesize carotenoids, but the yields are low and need to be studied [31].

3.2 Strategies for engineering microorganisms to synthesize lycopene

1) Upstream module (supply of precursors IPP/DMAPP) enhancement

To achieve high yields of carotenoids such as lycopene, increasing the synthesis of the general precursors IPP and DMAPP is an effective strategy. IPP and DMAPP synthesis involves two natural pathways, the MEP pathway and the MVA pathway. (a) The MEP pathway is mainly found in prokaryotes. DXS and IDI are generally considered to be the main rate-limiting enzymes in this pathway, and have been overexpressed to enhance isoprenoid synthesis [32]. Li et al. [33] found that IspA, ispH and ispE further increased the flux of the pathway in the DXS and IDI overexpressed strains. Overexpression of ispG can effectively reduce the outflow of MEC in the cell, resulting in a significant increase in the downstream isoprenoid production [34]. Based on this, Li et al. [35] successfully increased lycopene production by 77% by activating IspG and IspH to eliminate the accumulation of MEP intermediates. (b) The MVA pathway is mainly found in eukaryotes. HMG-CoA reductase is the first step in the biosynthesis of isoprenoid compounds via the MVA pathway [36]. The overexpression of the HMG-CoA reductase catalytic region (tHMG1) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae can increase the production of lycopene [24]. In addition, although some progress has been made in the production of carotenoids by optimizing the MEP pathway, the regulatory mechanisms of natural hosts in the MEP pathway limit its application [37]. In order to bypass this pathway, Zhu Fayin et al. [20] introduced the complete MVA pathway and exogenous genes into Escherichia coli, and obtained a lycopene yield of 1.44 g/L by batch feeding and fermentation optimization.

(2) Research on downstream modules (the lycopene heterologous synthesis pathway). A common strategy is to introduce heterologous pathway genes into non-carotenoid hosts to produce carotenoids, converting the terpene synthesis precursors IPP and DMAPP into carotenoids. Verwaal et al. [38] expressed a plasmid in E. coli containing genes encoding geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase and octahydro-lycopene synthase, as well as cDNA encoding lycopene desaturase, and ultimately observed the accumulation of lycopene. The introduction of copies of CrtI and tHMG1 into carotenoid-synthesizing yeast cells increased the β-carotene content. In order to achieve high-level and genetically stable expression of heterologous pathway genes, Tyo et al. [39] established a plasmid-free, high-gene-copy expression system for chemically induced chromosome evolution, which was used in engineered E. coli and ultimately increased lycopene production by 60% compared to the plasmid expression system. Studies have shown that optimizing the lycopene synthesis pathway is very important for heterologous high-yield lycopene.

3) Down-regulation of the bypass pathway

4) The precursor of lycopene synthesis, FPP, is also a common precursor of many yeast metabolites (such as ubiquinone, terpene alcohols, squalene, etc.). However, direct knockout of these precursor competitive pathway genes (such as the squalene synthesis gene) will have a great impact on cell growth. Therefore, many scholars are committed to down-regulating these competitive pathways to enhance the synthesis flux of lycopene. Substituting a weak promoter for the natural promoter to downregulate the competing squalene synthase gene sqs1 can increase the titratable yield of β-carotene from (453.9 ± 20.2) mg/L to (797.1 ± 57.2) mg/L in Yarrowia lipolytica [40]. Xie Wenping et al. [41] used the high glucose induction/low glucose repression promoter pHXT1 control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to achieve sequential expression of the erg9 gene and carotenoid pathway genes in response to changes in the glucose concentration in the culture, resulting in a significant increase in lycopene production in the yeast. Hong et al. [42] knocked out the dpp1 and lpp1 genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to suppress the competing pathway for the production of farnesol, and suppressed ergosterol production by downregulating erg9 expression, which also increased lycopene production. The above studies have fully demonstrated that downregulating competing pathways is an effective strategy for increasing lycopene production.

4) Transformation of the chassis cell

In addition to optimizing the lycopene heterologous synthesis pathway, the transformation of the host chassis cell is also required to match the heterologous pathway. Modification of the chassis cell includes: enhancing the flux of acetyl-CoA precursors [43], strengthening the supply of cofactors such as ATP and NADPH, knocking out certain non-essential genes, and adaptive evolution of the strain. Acetyl-CoA is the substrate for carotenoid biosynthesis. Chen Yan et al. [24] studied in detail the mechanism of action of the ypl062w gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Deletion of ypl062w can enhance the flux of acetyl coenzyme A and ultimately increase the production of lycopene, up to 1.65 g/L. Zhou et al. [26] used adaptive evolution of Saccharomyces cerevisiae combined with metabolic engineering techniques to achieved a batch fed fermentation yield of 8.15 g/L lycopene. The supply of ATP as energy and NADPH as reducing power is an important factor affecting carotenoid synthesis. By modifying the central metabolic modules for carbon source assimilation (EMP and PPP pathways), the supply of ATP and NADPH was enhanced, and engineered E. coli could synthesize 2.1 g/L β-carotene in batch fermentation [44]. Modulating the expression of the sucAB and sdhABCD genes can increase the carbon flux of the TCA cycle and increase the supply of ATP. In addition, modulating the talB gene can increase the supply of NADPH, which increases the yield of lycopene synthesis by E. coli to 3.52 g/L [45].

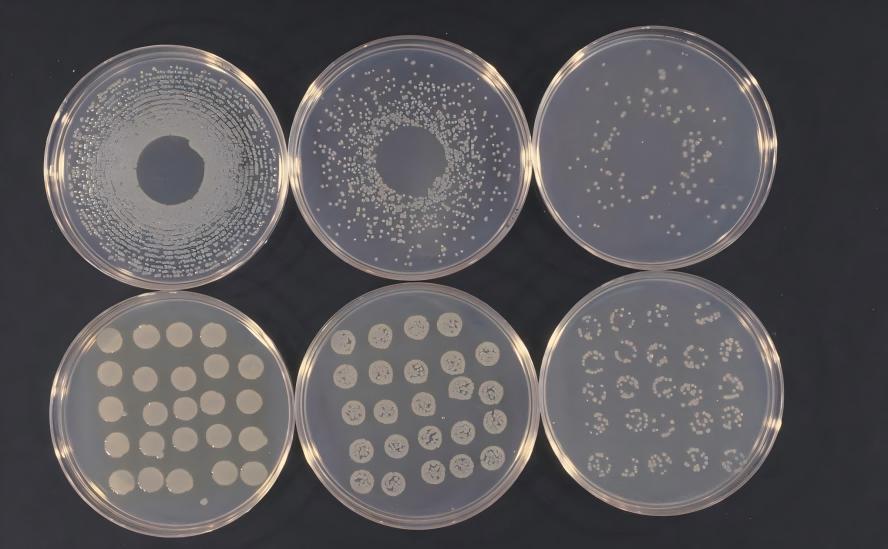

(5) Systematic metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to produce high-yield lycopene. A summary is shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Shi Bin et al. [25] systematically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae to efficiently biosynthesize lycopene through metabolic engineering, and listed four key issues: (a) the accumulation of secondary metabolites and host cell growth need to be balanced; (b) the heterologous synthesis pathway of lycopene needs to be enhanced in yeast; (c) the yeast chassis cells need to be modified to provide more precursor substances and reducing power; (d) the yeast fermentation technology needs to be optimized. and proposed corresponding solutions, including: (a) screening a group of GAL promoters that can reasonably control the lycopene heterologous synthesis pathway, separating yeast cell growth from lycopene product accumulation in terms of time sequence, and the promoter strength is also comparable to the constitutive strong promoter during the product synthesis period; (b) comprehensively screening the three key gene sources of the lycopene heterologous synthesis pathway, obtaining a new optimal combination of PaCrtE, PagCrtB, and BtCrtI that functions efficiently in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. (c) A series of modifications were also carried out on the Saccharomyces cerevisiae chassis cells to provide sufficient precursors for lycopene synthesis, acetyl coenzyme A and reducing power NADPH (reduced coenzyme II), and knocking out certain endogenous non-essential genes that affect lycopene accumulation to further increase lycopene production; (d) through these systems metabolic engineering methods, combined with the transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation processes to efficiently biosynthesize lycopene.

He listed four key issues: (a) the accumulation of secondary metabolites and host cell growth need to be balanced; (b) the lycopene heterologous synthesis pathway needs to be enhanced in yeast; (c) the yeast chassis cells need to be modified to provide more precursor substances and reducing power; (d) yeast fermentation technology needs to be optimized. and proposed corresponding solutions, including: (a) screening a group of GAL promoters that can reasonably control the lycopene heterologous synthesis pathway, separating yeast cell growth from lycopene product accumulation in terms of time sequence, and the promoter strength is also comparable to the constitutive strong promoter during the product synthesis period; (b) comprehensively screening the three key gene sources of the lycopene heterologous synthesis pathway, obtaining a new optimal combination of PaCrtE, PagCrtB, and BtCrtI that functions efficiently in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. (c) A series of modifications were also carried out on the Saccharomyces cerevisiae chassis cells to provide sufficient precursors for lycopene synthesis, such as acetyl coenzyme A and reducing power NADPH (reduced coenzyme II), and knocking out certain endogenous non-essential genes that affect lycopene accumulation to further increase lycopene production; (d) through these systems metabolic engineering methods, combined with the optimization of the fermentation of synthetic media by Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the lycopene yield was as high as 3.28 g/L, which has initially reached the industrial level. At present, the scale of Chinese-style fermentation has been successfully scaled up to 6,000 L. In addition, the strategy of metabolic engineering developed for Saccharomyces cerevisiae has also been successfully expanded to the biotechnological synthesis of other terpene compounds, such as β-farnesene [46], bergapten [47], and other sesquiterpenes such as β-caryophyllene. Among them, Deng Xiaomin et al. [47] used this system engineering strategy to increase the yield of bergapten produced by metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains to 34.6 g/L.

3.3 Fermentation process of lycopene engineered bacteria

At present, research on the fermentation of high-yield lycopene by microorganisms has also made great progress. The fermentation raw materials, processes and scales used by different strains will differ (summarized in Table 1). The substrate matrix used in the fermentation process varies with the type of microorganism. The fermentation hosts with more mature lycopene heterologous synthesis are generally Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In general, Escherichia coli fermentation uses glycerol as the carbon source [20, 45], while Saccharomyces cerevisiae mainly uses glucose as the carbon source [23-26].

Zhu Fayin et al. [20] used glycerol as the carbon source for engineered Escherichia coli and obtained a lycopene yield of 1.44 g/L using a fully synthetic medium in a 5 L fermenter. The fermentation scale was subsequently expanded to 150 L, yielding 1.32 g/L, indicating that the strain can be scaled up for production. Sun et al. [45] used engineered E. coli to ferment in a 7 L fermenter with glycerol as the carbon source in batch feeding, and ultimately obtained 3.52 g/L lycopene. Chen Yan et al. [24] used engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae to ferment glucose and ethanol as carbon sources and yeast extract and peptone as nitrogen sources in a 5 L fermenter using batch feeding.

They obtained a lycopene titer of 1.65 g/L. Shi Bin et al. [25] used engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae to carry out two-stage fed-batch fermentation in a 7 L fermenter using glucose and ethanol as carbon sources and ammonium sulfate as a nitrogen source. The glucose and ethanol residuals in the fermentation broth were strictly controlled, and a final lycopene titer of 3.28 g/L was obtained. Since Saccharomyces cerevisiae has many advantages over Escherichia coli, such as high food safety and resistance to phage infection, research on the fermentation of lycopene by Saccharomyces cerevisiae is more promising. At present, natural YPD media, which often use peptone and yeast extract as nitrogen sources for yeast fermentation [24, 26], as well as semi-synthetic media with ammonium sulfate, yeast extract, and peptone as mixed nitrogen sources [23], and fully synthetic media with ammonium sulfate as the nitrogen source [25]. Fully synthetic media have the advantages of being inexpensive, easy to ferment repeatedly and scaled up, and having clear composition which is convenient for later optimization. In the future, more research should be done on the fermentation of synthetic yeast media to make lycopene production high and stable, repeatable, and scalable, laying a solid foundation for subsequent industrial applications.

3.4 Extraction and quantification of lycopene synthesized by microorganisms

Carotenoids such as lycopene have strong antioxidant properties, and the risk of oxidation and isomerization must be minimized during the extraction process [49]. For example, some studies have chosen to operate under light-protected conditions [20, 45], or add the antioxidant BHT to the extraction agent [24-25, 27]. Commonly used extraction solvents are acetone, petroleum ether, chloroform, hexane, ethyl acetate, etc. [49]. Since lycopene is an intracellular product, cell wall disruption is required, and the method of cell wall disruption varies depending on the thickness of the host cell wall. For example, the cell wall of Escherichia coli is relatively thin, acetone resuspension is generally used, followed by cell wall destruction in a 55 °C water bath [20, 45]; eukaryotic organisms such as lipid-soluble yeast and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have thicker cell walls, and glass beads and extraction reagents are usually added to break the cells by shaking [25, 27]; the yeast cell wall can also be broken by boiling in a water bath with hydrochloric acid [23-24].

The methods used to detect and quantify carotenoids such as lycopene also vary in the existing studies. Most studies use high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to detect carotenoids such as lycopene and β-carotene [23-26, 45], while a few use ultraviolet-spectrophotometry [20, 27]. Because the UV-spectrophotometer detection is interfered by impurities with the same absorption wavelength, and the HPLC method detects by first separating different substances and then detecting the absorption value. Relatively speaking, the accurate quantification of carotenoids such as lycopene by HPLC is more accurate, while UV-spectrophotometer detection can be used as a supplementary means to initially assess the trend of yield changes during fermentation.

Most studies used a standard curve with corresponding lycopene and β-carotene standards to calculate the yield [23-26, 45], but did not indicate whether the purchased lycopene/β-carotene standards were calibrated. Only a few researchers explicitly stated that the concentration of the standard solution had been calibrated before drawing the standard curve [25]. The reason why the concentration of the prepared standard solution must be calibrated is that it is difficult to accurately weigh a small amount of lycopene or β-carotene standard, and it is not easy to accurately determine whether the lycopene crystals in the organic solvent have completely dissolved. In addition, the purity of the purchased standard may also change due to storage methods and time. These objective factors may cause large errors in the drawing of the lycopene standard curve, resulting in the calculated yield not being highly accurate. In order to eliminate the interference of the above factors, the common method is to first use a spectrophotometer to measure the absorbance of the prepared lycopene and other carotenoid standard solution, and then calculate the absolute content of the carotenoids in the solution according to the corresponding extinction coefficient [25, 50-51]. This method can eliminate errors caused by inaccurate weighing or incomplete dissolution of the sample. In summary, HPLC is used to accurately detect lycopene in the sample, and a standard curve is plotted using a calibrated standard solution, and the quantitative results will be more accurate.

4 Conclusion and outlook

Lycopene, as a strong antioxidant, has many good physiological functions and has a broad market prospect. This paper provides a detailed review of the physicochemical properties, physiological functions and production methods of lycopene, and focuses on summarizing the current research progress in the production of lycopene by biotechnology, including the diversity selection of microbial host cells, the latest metabolic engineering strategies, fermentation methods and lycopene extraction and accurate quantification methods.

Although some progress has been made in the biotechnological synthesis of lycopene, there are still many problems with the lycopene biosynthesis process because it is a complex engineering research project with many influencing factors. The following summarizes the relevant research directions for the future:

(1) Scale-up and stable replication of fermentation production. At present, most research on the biotechnological synthesis of lycopene is still at the laboratory stage of small-scale fermentation tank experiments, while industrial research is often based on large-scale fermentation production calculated in tons or tens of tons. Fermentation scale-up from small-scale to pilot production is not simply a linear increase in tank volume, but also involves many challenges such as uneven heat transfer, mass transfer, and oxygen transfer, as well as changes in the growth model of the strain. According to the author's practical experience, during the process of fermentation amplification of engineered strains, problems such as premature strain aging, strain phenotype degradation, changes in feeding strategies, and unstable fermentation yields may occur. Researchers need to individually adjust the parameters and conditions of the fermentation process amplification. Future research on the amplification of fermentation production scale is the key to solving the problem of industrial production of lycopene using biotechnology.

(2) Extraction and purification process of lycopene from microbial sources. Lycopene is an intracellular product, and the extraction and purification process involves many steps such as cell disruption, impurity removal, and lycopene crystallization. During this process, lycopene is easily oxidized, which leads to structural changes. Therefore, the extraction rate is difficult to ensure, and in-depth research is needed on the extraction and purification process of lycopene from microbial sources.

(3) Research on quality testing of microbial lycopene. Although microbial lycopene is also a product of enzymatic catalysis, it is not derived from natural tomatoes and may involve issues such as genetic modification. Therefore, microbial lycopene must first be structurally identified to ensure that it is consistent with natural tomato sources, and then quality testing of product quality such as heavy metal residues and microbial content is required. Ensuring the structure and quality of the product is also an important factor affecting the market application of microbial lycopene.

(4) Production cost control: If it is to compete in the market with naturally extracted lycopene, biotechnologically synthesized lycopene must have a significant cost advantage. The main costs of biologically fermenting to produce lycopene include fermentation raw materials, depreciation of equipment, extraction and purification, labor, and marketing. Cost factors must be considered when designing and optimizing production process conditions, such as using cheaper fully synthetic fermentation media, spreading costs by scaling up fermentation, and using more advanced methods such as enzymatic cell disruption to extract lycopene to reduce production costs.

Solving these problems is of great theoretical and practical significance for promoting the industrialization of lycopene production by biotechnology, and can also provide a reference for research on the biotechnology production of other high value-added natural products.

References

[1] Protective effect of MK-4 on oxidation of carot⁃ enoids in simulated gastric juice[J].Journal of Huazhong Agri⁃ cultural University,2020,39(2): 102-111(in Chinese with English abstract).

[2]LIU K Y,LIU X Y,WANG Q,et al. Optimization of main ingredient ratio of compound fruit and vegetable wine rich in lycopene by D-optimal mixture design[J].China brew⁃ ing,2022,41(2):164-169

[3] ZARDINI A A,MOHEBBI M,FARHOOSH R,et al. Production and characterization of nanostructured lipid carriers and solid lipid nanoparticles containing lycopene for food fortifi⁃ cation[J]. Journal of food science and technology,2018,55 (1):287-298 .

[4] LEE M T,CHEN B H. Stability of lycopene during heating and illumination in a model system[J].Food chemistry,2002, 78(4):425-432 .

[5]WANG X W,XIA Y B,WANG K Q.Stability of natural lycopene[J].Journal of Hunan Agricultural University,2002,28(1):57-60 (in Chinese with English abstract).

[6]MA T G.Physiological functions and application of Lycopene[J]. Cereals & oils,2008,21(1):46-48(in Chi⁃ nese with English abstract).

[7]LI J,YAN W,LIU Y H,et al. Research progress on health function and application of lycopene[J].Agriculture and technology,2016,36(15):5-6 (in Chinese).

[8]JIANG L H,LIU H F,HAO G F,et al.Research progress on antioxidant ability of astaxanthin[J].Science and technology of food industry,2019, 40(10):350-354.

[9]PENG Y J,LÜ H P, WANG S N,et al. Present research and prospect on natural astaxanthin[J]. China food additives,2017(4): 193-197.

[10] ASSAR E A,VIDALLE M C,CHOPRA M,et al.Lycopene acts through inhibition of IκB kinase to suppress NF-κB signal⁃ ing in human prostate and breast cancer cells[J].Tumor biolo⁃ gy,2016,37(7):9375-9385 .

[11] RAO A V,AGARWAL S. Role of antioxidant lycopene in cancer and heart disease[J].Journal of the American college of nutrition,2000,19(5):563-569 .

[12]HUO S X,YANG Q S,YUE X H,et al.Determination method of lycopene content in tomato skin[J]. The food industry,2019,40(6):263-265 (in Chinese with English abstract).

[13] KARL M.Method for the manufacture of carotinoids and novel intermediates:US5208381[P].1993-05-04.

[14] KIRBY J,KEASLING J D.Biosynthesis of plant isoprenoids: perspectives for microbial engineering[J]. Annual review of plant biology,2009,60:335-355 .

[15] ROHMER M,KNANI M,SIMONIN P,et al.Isoprenoid bio⁃ synthesis in bacteria:a novel pathway for the early steps lead⁃ing to isopentenyl diphosphate[J]. The biochemical journal, 1993,295(Pt 2):517-524 .

[16] BLOCH K,CHAYKIN S,PHILLIPS A H,et al. Mevalonic acid pyrophosphate and isopentenylpyrophosphate[J]. Journal of biological chemistry,1959,234(10):2595-2604 .

[17] CHOUDHARI S M,ANANTHANARAYAN L,SING⁃ HAL R S. Use of metabolic stimulators and inhibitors for en⁃ hanced production of β-carotene and lycopene by Blakeslea tri⁃ spora NRRL 2895 and 2896[J].Bioresource technology,2008, 99(8):3166-3173 .

[18]ANATES T M R,DE CASTROTES A E, PEREZTES J C. Improved method of producing lycopene, preparation for obtaining lycopene,and application thereof: CN1617934A[P].2005-05-18.

[19] WANG J F,LIU X J,LIU R S,et al.Optimization of the mat⁃ ed fermentation process for the production of lycopene by Blakeslea trispora NRRL 2895( + )and NRRL 2896 ( − ) [J]. Bioprocess and biosystems engineering,2012,35(4): 553-564.

[20] ZHU F Y,LU L,FU S,et al.Targeted engineering and scale up of lycopene overproduction in Escherichia coli[J]. Process biochemistry,2015,50(3):341-346 .

[21] PARK S Y,BINKLEY R M,KIM W J,et al.Metabolic engi⁃ neering of Escherichia coli for high-level astaxanthin produc⁃ tion with high productivity[J]. Metabolic engineering,2018, 49:105-115 .

[22] RAY B L,RAETZ C R. The biosynthesis of gram -negative endotoxin .A novel kinase in Escherichia coli membranes that incorporates the 4'-phosphate of lipid A[J]. Journal of biologi⁃ cal chemistry,1987,262(3):1122-1128 .

[23] XIE W P,LV X M,YE L D,et al. Construction of lycopene- overproducing Saccharomyces cerevisiae by combining direct⁃ ed evolution and metabolic engineering[J].Metabolic engineer⁃ ing,2015,30:69-78 .

[24] CHEN Y,XIAO W H,WANG Y,et al.Lycopene overproduc⁃ tion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through combining pathway engineering with host engineering[J/OL].Microbial cell facto⁃ ries,2016,15(1):113[2023-03-13].https://microbialcellfac⁃ tories . biomedcentral. com/articles/10.1186/s12934-016- 0509-4.

[25] SHI B,MA T,YE Z L,et al. Systematic metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for lycopene overproduction [J]. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry,2019,67(40): 11148-11157.

[26] ZHOU K,YU C,LIANG N,et al. Adaptive evolution and metabolic engineering boost lycopene production in Saccharo⁃ myces cerevisiae via enhanced precursors supply and utilization[J]. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry,2023,71(8): 3821-3831.

[27] GAO S L,TONG Y Y,ZHU L,et al. Iterative integration of multiple-copy pathway genes in Yarrowia lipolytica for heter⁃ ologous β -carotene production[J]. Metabolic engineering, 2017,41:192-201 .

[28] LARROUDE M,CELINSKA E,BACK A,et al.A synthetic biology approach to transform Yarrowia lipolytica into a com⁃ petitive biotechnological producer of β-carotene[J].Biotechnol⁃ ogy and bioengineering,2018,115(2):464-472 .

[29] GUERIN M,HUNTLEY M E,OLAIZOLA M.Haematococ⁃ cus astaxanthin:applications for human health and nutrition[J].Trends in biotechnology,2003,21(5):210-216 .

[30] DIAS C,SILVA C,FREITAS C,et al.Effect of medium pH on Rhodosporidium toruloides NCYC 921 carotenoid and lip⁃ id production evaluated by flow cytometry[J]. Applied bio⁃ chemistry and biotechnology,2016,179(5):776-787 .

[31] BHATAYA A,SCHMIDT-DANNERT C,LEE P C. Meta⁃ bolic engineering of Pichia pastoris X-33 for lycopene produc⁃ tion[J].Process biochemistry,2009,44(10):1095-1102 .

[32] YANG J M,GUO L Z. Biosynthesis of β -carotene in engi⁃ neered E.coli using the MEP and MVA pathways[J].Microbi⁃ al cell factories,2014,13:160 .

[33] LI Y F,LIN Z Q,HUANG C,et al.Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using CRISPR-Cas9 meditated genome edit⁃ ing[J].Metabolic engineering,2015,31:13-21 .

[34] ZHOU K,ZOU R Y,STEPHANOPOULOS G,et al.Metab⁃ olite profiling identified methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate ef⁃ flux as a limiting step in microbial isoprenoid production[J]. PLoS One,2012,7(11):e47513 .

[35] LI Q Y,FAN F Y,GAO X,et al.Balanced activation of IspG and IspH to eliminate MEP intermediate accumulation and im⁃ prove isoprenoids production in Escherichia coli[J]. Metabolic engineering,2017,44:13-21 .

[36] DIMSTER-DENK D,THORSNESS M K,RINE J. Feed⁃ back regulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A re⁃ ductase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Molecular biology of the cell,1994,5(6):655-665 .

[37] MARTIN V J J,PITERA D J,WITHERS S T,et al. Engi⁃ neering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for produc⁃ tion of terpenoids[J]. Nature biotechnology,2003,21(7): 796-802.

[38] VERWAAL R,WANG J,MEIJNEN J P,et al. High-level production of beta-carotene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by successive transformation with carotenogenic genes from Xan⁃ thophyllomyces dendrorhous[J]. Applied and environmental microbiology,2007,73(13):4342-4350 .

[39] TYO K E J,AJIKUMAR P K,STEPHANOPOULOS G. Stabilized gene duplication enables long-term selection-freeheterologous pathway expression[J]. Nature biotechnology, 2009,27(8):760-765 .

[40] KILDEGAARD K R,ADIEGO-PÉREZ B,DOMÉNECH BELDA D,et al. Engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for pro⁃ duction of astaxanthin[J]. Synthetic and systems biotechnolo⁃ gy,2017,2(4):287-294 .

[41] XIE W P,YE L D,LÜ X M,et al.Sequential control of biosynthetic pathways for balanced utilization of metabolic inter⁃ mediates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Metabolic engineer⁃ ing,2015,28:8-18 .

[42] HONG J,PARK S H,KIM S,et al.Efficient production of lycopene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by enzyme engineering and increasing membrane flexibility and NAPDH production [J]. Applied microbiology and biotechnology,2019,103(1): 211-223.

[43]LI J R,LIN J Y,LI Z Y,et al.Mining and regulating acetic acid stress-responsivegenes to improve lycopene syn⁃ thesis in recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J/OL].Micro⁃ biology China,2023:1-24[2023-03-13].

[44] ZHAO J,LI Q Y,SUN T,et al.Engineering central metabolic modules of Escherichia coli for improving β -carotene produc⁃ tion[J].Metabolic engineering,2013,17:42-50 .

[45] SUN T,MIAO L T,LI Q Y,et al.Production of lycopene by metabolically-engineered Escherichia coli[J]. Biotechnology letters,2014,36(7):1515-1522 .

[46] YE Z L,SHI B,HUANG Y L,et al.Revolution of vitamin E production by starting from microbial fermented farnesene to isophytol[J/OL].The innovation,2022,3(3):100228[2023- 03-13].https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn .2022.100228.

[47] DENG X M,SHI B,YE Z L,et al.Systematic identification of Ocimum sanctum sesquiterpenoid synthases and (−) -eremophilene overproduction in engineered yeast[J].Metabolic engi⁃ neering,2022,69:122-133 .

[48] LUO Z S,LIU N,LAZAR Z,et al.Enhancing isoprenoid syn⁃ thesis in Yarrowia lipolytica by expressing the isopentenol utilization pathway and modulating intracellular hydrophobicity [J].Metabolic engineering,2020,61:344-351 .

[49] CHOKSI P M,JOSHI V Y.A review on lycopene:extraction, purification,stability and applications[J].International journal of food properties,2007,10(2):289-298 .

[50] BIAN G K,MA T,LIU T G.In vivo platforms for terpenoid overproduction and the generation of chemical diversity[J]. Methods in enzymology,2018,608:97-129 .

[51] SCOTT K J. Detection and measurement of carotenoids by UV/VIS spectrophotometry[J].Current protocols in food ana⁃ lytical chemistry,2001,F2 .2(1):1-10 .

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese