Study on Natural Coloring Astaxanthin

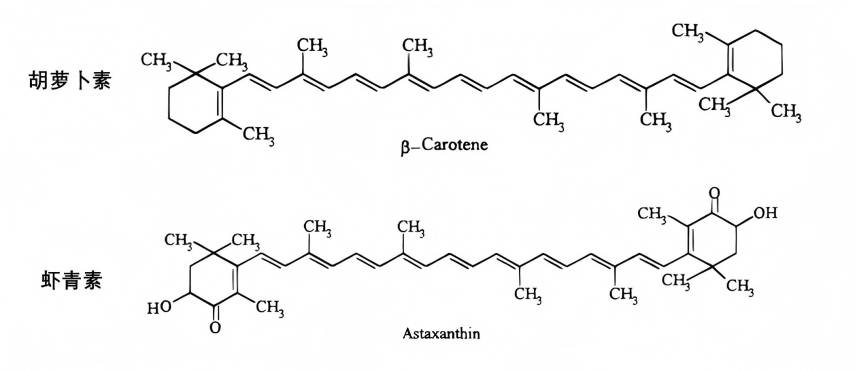

To date, at least 600 types of natural carotenoids have been discovered by humans. Carotenoids can be divided into two categories based on whether or not they contain oxygen in their chemical structure: one type is the oxygen-containing carotenoid—the xanthophyll group, which includes lutein and astaxanthin; the other type is the oxygen-free carotenoid—the carotene group, which includes β-carotene and lycopene [1].

Astaxanthin is widely found in nature, but higher organisms cannot synthesize it and generally obtain it through diet. Natural astaxanthin is mainly biosynthesized by microalgae or phytoplankton, and then accumulates in zooplankton and crustaceans, and then appears in higher organisms such as fish and birds through predation relationships. In addition, some yeasts and bacteria can also synthesize astaxanthin, but the astaxanthin they synthesize differs in structure, as shown in Table 1.

Astaxanthin with different structures can show significant differences in physiological function. All-trans astaxanthin is the most stable form of existence, while cis-leucastin has better biological activity than other astaxanthin structures [2]. Currently, 95% of astaxanthin on the market is synthesized using petrochemical products. However, synthetic astaxanthin has no known human safety studies and has never been shown to have any health benefits in human clinical trials. Therefore, synthetic astaxanthin is not approved by the FDA as a dietary supplement for humans[3]. Natural astaxanthin extracted from Haematococcus pluvialis is mainly in the all-trans form and is currently the main source of astaxanthin as a dietary supplement for humans [4]. In some clinical studies, astaxanthin has been shown to be an effective preventive and therapeutic agent for various diseases. This article reviews the bioavailability and physiological functions of astaxanthin, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cognitive function improvement, and DNA damage repair. It also attempts to identify gaps in current research on the biological activity of astaxanthin and provide theoretical guidance for functional research on astaxanthin.

1 Astaxanthin bioavailability

Due to the hydrophobic nature of astaxanthin, its intestinal absorption mechanism is similar to that of dietary lipids. That is, under the action of digestive enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract of animals, it is separated from its protein-bound complex, emulsified with other lipid substances in the duodenum by bile to form chylomicrons, which automatically diffuse to the surface of the intestinal wall and are then absorbed by intestinal mucosal cells and subsequently released into the lymphatic system. Once the chylomicrons have been digested by lipoprotein lipase in the liver, astaxanthin is assimilated with the lipoproteins, especially LDL, and further distributed to other tissues [5]. The absorption of astaxanthin is affected by its chemical properties, dietary and non-dietary related parameters [1].

As shown in Table 2, the form in which it is present and whether it is bound to other compounds (e.g. proteins, fats) is a direct factor influencing the degree of astaxanthin absorption; heating or extrusion can indirectly affect absorption by causing the destruction of cell walls and thus promoting the release of astaxanthin; as the body ages, any disease related to abnormal fat absorption in the digestive tract can significantly affect the absorption of astaxanthin [6]. After being absorbed and metabolized by intestinal epithelial cells, astaxanthin can exist in different forms in the body's plasma. It has been reported that after ingesting astaxanthin, the blood levels of the cis isomer are significantly higher than those of the all-trans isomer[7], but the reason for this has not been analyzed.

Recent research has found that the astaxanthin cis-isomers present in human plasma are mainly 13-cis and 9-cis isomers. The reason for their high levels in human plasma is that after the body ingests food that is rich in all-trans astaxanthin, during the digestion and absorption process in the body, all-trans astaxanthin isomerized to form cis-isomers due to various factors. and the cis-astaxanthin has high bioavailability and a high rate of secretion by cells, which is beneficial for its absorption in the human body [8]. The geometric isomers of astaxanthin in the human body have been studied and proven, and there have been fewer reports on the stereoisomers of astaxanthin in the body. It has not been indicated whether astaxanthin exists in the form of levoglucose or dextrose, and this issue should be of concern.

2 Physiological functions of astaxanthin

2.1 Antioxidant activity

Astaxanthin neutralizes free radicals or other oxidants by accepting or providing electrons, and in the process is not destroyed or becomes a pro-oxidant. Its linear, polar-nonpolar molecular layout allows it to precisely insert into the membrane and span its entire width without destroying the cell membrane [9]. These properties of astaxanthin lay the foundation for its antioxidant and other effects in the body. Free radicals, most of which are oxygen radicals, are produced during the course of human life and movement. The electron-scavenging ability of antioxidants is crucial for eliminating excessive free radicals in the body [10]. Table 3 compares the free radical scavenging abilities of natural antioxidants. Based on current research, astaxanthin is the most suitable for scavenging singlet oxygen and superoxide anion radicals. During singlet oxygen quenching, energy is transferred from the singlet oxygen to the astaxanthin molecule.

The energetically rich astaxanthin molecule can then return to the ground state by releasing the energy as heat, leaving the astaxanthin molecule not only intact, but also ready for the next quenching of singlet oxygen [17]. B. Capelli et al. [14] concluded in their experiment to determine the scavenging of superoxide anion radicals by natural antioxidants that compared to antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene and pycnogenol, astaxanthin not only has 14–16 times higher antioxidant activity in scavenging free radicals, but is also about 20 times higher than synthetic astaxanthin. However, a recent study by Janina Dose et al. [18] contradicts the results of a study by B. Capelli et al. and shows that synthetic astaxanthin is unable to scavenge superoxide anion radicals. The reason for this discrepancy may be differences in experimental methods or conditions, or it may be that synthetic astaxanthin itself has no antioxidant capacity. Whether antioxidant capacity is related to the purity of the antioxidant has not been shown in the relevant literature.

2.2 Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammatory responses are a critical part of the body's healthy immune function, but chronic inflammation is generally considered to be the root cause of various health problems, including atherosclerosis, skin damage, neurodegeneration, tumors, and immune disorders. Astaxanthin's ability to shuttle throughout the body allows it to target many highly stressed inflammatory areas such as the heart, brain, eyes, and skin, thereby exerting its anti-inflammatory effect. Table 4 shows experimental studies on the anti-inflammatory activity of astaxanthin.

Atherosclerosis (AS) is the main cause of coronary heart disease, cerebral infarction, and peripheral vascular disease. Recent studies on AS have focused on inflammation, providing new insights into the mechanism of the disease. It is believed that AS is a disease characterized by chronic inflammatory changes, and many inflammatory signaling pathways are associated with the early occurrence, progression, and ultimately acute complications of AS [27]. Astaxanthin can reduce excessive liver lipid accumulation and peroxidation, activate stellate cells to improve liver inflammation and fibrosis [19], making it a potentially new and promising treatment for atherosclerosis. Sustained oxidative stress is a key mechanism leading to chronic inflammation.

The main causes of UV-induced skin inflammation are intracellular reactive nitrogen/oxygen species production and keratinocyte apoptosis. Astaxanthin causes a significant decrease in inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 levels, and also reduces the release of prostaglandin E2 from keratinocytes after UV irradiation, thereby inhibiting keratinocyte apoptosis [20]. Astaxanthin's inhibitory effect on iNOS is of great significance for the development of anti-inflammatory drugs for skin in inflammatory diseases. An increase in pro-inflammatory factor concentrations and a decrease in the production of anti-inflammatory mediators are characteristic of the ageing brain and are also pathological features of many neurodegenerative diseases. Microglial cells are resident macrophages of the brain and are closely involved in the immune response of the CNS [28]. With age, the CNS response becomes dysregulated, characterized by an increase in basal output of proinflammatory factors in the absence of immune stimuli and insensitivity to regulatory signals that terminate microglial activation, resulting in damage to neural tissue [27].

Astaxanthin can specifically regulate microglial cell function. Balietti et al. [22] observed that astaxanthin reduced IL-1β in the hippocampus and cerebellum of aged female rats by feeding astaxanthin to aged rats, and detected an increase in IL-10 in the cerebellum of female rats and the hippocampus of male rats. suggesting that astaxanthin supplementation can differently alter cytokine activity in different sexes to achieve the purpose of treating neurodegenerative diseases. Chronic inflammation is also one of the hallmarks of cancer. Inflammatory responses are often related to microbial responses. There are countless bacterial strains in the intestine, which usually coexist in harmony with the host, but any substantial change in the bacterial community can have a considerable impact on the inflammatory response and promote tumor development [29]. Recent studies have shown that the flora structure of prostate cancer patients and benign prostatic hyperplasia is basically similar, while the number of specific species varies greatly between the groups. Astaxanthin (100 mg/kg) can inhibit tumor growth by inhibiting the growth of Lactobacillus species.

Immune cells are particularly sensitive to oxidative stress because they contain a high percentage of polyunsaturated fatty acids in their plasma membranes, which normally produce more oxidative products. Excessive production of reactive oxygen species and nitrogen species can cause a imbalance in the body's oxidant and antioxidant balance, leading to damage to cell membranes, proteins and DNA [30]. Astaxanthin can significantly affect immune function. In a high-temperature stress test, dietary astaxanthin supplementation (80–320 mg/kg) significantly increased the expression of pufferfish SOD, CAT and HSP70 genes, inhibited high-temperature-induced ROS production, improved growth performance and enhanced non-specific immunity [25]. In addition, the immunomodulatory effect of astaxanthin can also act on specific immunity. Liu Yingfen et al. [26] proved in an experiment exploring the effect of astaxanthin on mouse immunity that Haematococcus pluvialis astaxanthin can enhance specific immune responses such as lymphocyte proliferation.

2.3 Improves cognitive function

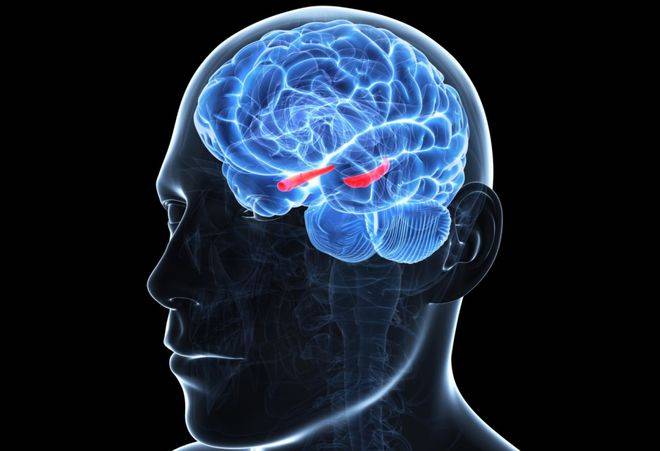

Doxorubicin (DOX) is one of the most effective and basic antineoplastic drugs approved by the FDA for the treatment of many types of cancer [31]. Despite its outstanding clinical efficacy, DOX can also cause strong neurotoxicity, manifested as symptoms such as memory impairment, slow reaction, inattention, and speech difficulties. Studies have shown that astaxanthin treatment (25 mg/kg) can stop DOX-induced oxidative and inflammatory damage, prevent the release of inflammatory mediators, inhibit the activation of glial cells, inhibit overactive AChE enzymes, and maintain mitochondrial integrity, thereby avoiding cognitive dysfunction caused by DOX [32]. The mechanism is shown in Figure 1. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a serious health hazard. Its pathogenesis is a series of cascading reactions induced by direct physical trauma or secondary injury, leading to neuronal death, activation of chronic inflammation, and ultimately neurodegeneration, which seriously affects the body's motor, cognitive, and intellectual functions and other health [33]. Some studies have found that after oral administration of AST in a TBI model, the size of the lesion in the cortex is reduced and the loss of neurons is also reversed. The levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, synaptic protein and synaptin in the cerebral cortex are also restored, which improves neuronal survival and plasticity, thereby promoting the recovery of cognitive function [34].

2.4 Repairing DNA damage

Human cells produce a large number of different types of DNA damage every day under the action of endogenous and exogenous DNA damage factors. However, human cells also have a relatively comprehensive DNA repair mechanism to deal with these damages, restore the integrity and fidelity of the DNA, and thus maintain genetic stability. DNA damage response is the cornerstone of maintaining genomic stability in cells. Defects in it can lead to the occurrence and development of various diseases, including cancer. Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent widely used in cancer therapy. However, it is severely cytotoxic to normal cells in humans and experimental animals, and its toxic effects are associated with genomic instability and DNA damage. Astaxanthin has been shown to exert its protective effect against cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway and regulating the gene expression of NQO-1 and HO-1 [35]. Protein kinase B plays an important role in regulating DNA damage response and genomic stability. Studies have shown that inhibiting protein kinase B activity affects the repair of DNA double strand breaks, while astaxanthin regulates the protein kinase B signaling pathway. This regulatory effect helps maintain genomic stability and counteract DNA damage [3].

3 Conclusion

Natural astaxanthin has been confirmed by toxicological tests to be a safe and bioavailable compound. Astaxanthin products are currently widely consumed as dietary supplements in Europe, Japan and the United States. The FDA recommends an optimal intake of 4–6 mg of astaxanthin dietary supplements per day, with a maximum of 12 mg [3]. Astaxanthin also has a good market in many fields such as cosmetics (creams, lip balms, etc.), the feed industry (feed additives), the pharmaceutical industry (the American company Cyanotech has launched astaxanthin drugs to relieve exercise fatigue), and the food industry (colorants).

Based on the above references and experimental data (not comprehensive), there may be the following experimental shortcomings and outstanding issues in the research on astaxanthin. Exploring different solutions to deal with these research deficiencies will help astaxanthin become a valuable option for the prevention and treatment of various acute and chronic diseases.

(1) The state in which astaxanthin is produced needs to be clarified for experimental data, including the cis-trans isomers of astaxanthin and the degradation or oxidation products of astaxanthin.

(2) Experimental support is needed for the optimal preventive/therapeutic dose of astaxanthin for in vivo experiments.

(3) There have been relatively few studies on the combined effects of astaxanthin and drugs.

(4) Do astaxanthins from different sources have different effects when used in the same experiment?

(5) There is a lack of research on the excretion of astaxanthins after astaxanthin intervention tests on organisms.

(6) Where does astaxanthin go after an astaxanthin intervention test on an organism is terminated?

(7) In what state (solid, semi-solid, liquid) does astaxanthin enter the body when taken?

Reference:

[1] VISIOLI F, ARTARIA C. Astaxanthin in cardiovascular health and disease: mechanisms of action, therapeutic merits, and knowledge gaps[J]. Food Function, 2017, 8(1): 39–63.

[2] Liu Han, Chen Xiaofeng, Liu Xiaojuan, et al. In vitro antioxidant effects of astaxanthin with different geometric configurations and its protective effect on oxidative stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Science, 2019, 40(3): 178-185.

[3] DAVINELLI S, NIELSEN M, SCAPAGNINI G. Astaxanthin in skin health, repair, and disease: a comprehensive review[J]. Nutrients, 2018, 10(4): 522.

[4] M M R SHAH, Y LIANG, J J, et al. Astaxanthin-producing green microalga haematococcuspluvialis: from single cell to high value commercial products, front[J]. Plant Sci., 2016, 7, 531.

[5] Liu Helu, Zheng Huaiping, Zhang Tao, et al. Metabolism and transport and deposition of astaxanthin in seafood animals [J]. Marine Science, 2010, 34(4): 104-108.

[6] FIEDOR J, BURDA K. Potential role of carotenoids as antioxidants in human health and disease[j]. Nutrients, 2014, 6(2): 466–488.

[7] ØSTERLIE, M. Plasma appearance and distribution of astaxanthin E/Z and R/S isomers in plasma lipoproteins of men after single dose administration of astaxanthin[J]. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2000, 11(10): 482–490.

[8] Yang, Cheng. Preparation, purification, absorption and metabolism, and effects on intestinal function of isomers of oxygenated carotenoids [D]. Jiangnan University, 2018.

[9] KIDD P. Astaxanthin, cell membrane nutrient with diverse clinical benefits and anti-aging potential[J]. Alternative Medicine Review. 2011, 16: 355–364.

[10] Li Yun. A review of the effects of free radicals on human health and current preventive measures [J]. Inner Mongolia Petrochemical Industry, 2011, 37(01): 87-89.

[11] Y NISHIDA, E YAMASHITA, W MIKI. Quenching activities of common hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants against singlet oxygen using chemiluminescence detection system[J]. Carotenoid Sci, 2007, 11: 16 –20.

[12]SUEISHI Y, ISHIKAWA M, YOSHIOKA M, et al. Oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) of cyclodextrin-solubilized flavonoids, resveratrol and astaxanthin as measured with the ORAC-EPR method[J]. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition, 2012, 50(2): 127–132.

[13]CHANG C S, CHANG C L, LAI G H. Reactive oxygen species scavenging activities in a chemiluminescence model and neuroprotection in rat pheochromocytoma cells by astaxanthin, beta-carotene, and canthaxanthin[J]. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 2013, 29(8): 412–421.

[14] B CAPELLI, D BAGCHI, G CYSEWSKI. Synthetic astaxanthin is significantly inferior to algal-based astaxanthin as an antioxidant and may not be suitable as a human nutritional supplement[J]. NutraFoods, 2013(12): 145–152.

[15] P REGNIER, J BASTIAS, V RODRIGUEZ-RUIZ, et al., Astaxanthin from haematococcuspluvialis prevents oxidative stress on human endothelial cells without toxicity[J]. Mar. Drugs, 2015, 13(5): 2857–2874.

[16] Liu Xiaoxing. Comparative study of the antioxidant activity of astaxanthin and five natural antioxidants [D]. Hebei University of Engineering, 2018.

[17] F BOHM, R EDHE, T G. Truscott. Interactions of dietary carotenoids with singlet oxygen (1O2) and free radicals: potential effects for human health[J]. Acta Biochim Polonica, 2012, 59(1): 27–30.

[18] DOSE J, MATSUGO S, YOKOKAWA H, et al. Free radical scavenging and cellular antioxidant properties of astaxanthin[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2016, 17(1): 103.

[19] Y Ni, M NAGASHIMADA, F ZHUGE, et al, Astaxanthin prevents and reverses dietinduced insulin resistance and steatohepatitis in mice: A comparison with vitamin E[J]. Scientific Reports, 2015(5): 17192.

[20] YOSHIHISA Y, REHMAN M U, SHIMIZU T. Astaxanthin, a xanthophyll carotenoid, inhibits ultraviolet-induced apoptosis in keratinocytes[J]. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23: 178–183.

[21] PARK, J H, YEO, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of astaxanthin in phthalic anhydride-induced atopic dermatitis animal model[J]. Experimental Dermatology, 2018, 27(4): 378–385.

[22] BALIETTI M, GIANNUBILO S R, GIORGETTI B, et al. The effect of astaxanthin on the aging rat brain: gender-related differences in modulating inflammation[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2015, 96(2): 615–618.

[23] ZHOU X, ZHANG F, HU X, et al. Inhibition of inflammation by astaxanthin alleviates cognition deficits in diabetic mice[J]. Physiology & Behavior, 2015, 151: 412–420.

[24] Ni Xiaofeng. Research on the antioxidant effect of astaxanthin and its biological mechanism of action on prostate cancer [D]. Zhejiang University, 2017.

[25] CHENG C H, GUO Z X, YE C X, et al. Effect of dietary astaxanthin on the growth performance, non-specific immunity, and antioxidant capacity of pufferfish (Takifuguobscurus) under high temperature stress[J]. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry, 2017, 44(1): 209–218.

[26] Liu Yingfen, Xin Naihong, Li Bingqian et al. Research on the immunomodulatory effect of Haematococcus pluvialis astaxanthin in mice [J]. Food Research and Development, 2017, 38(20): 183-187.

[27] B GRIMMIG, S KIM, K NASH, et al. Neuroprotective mechanisms of astaxanthin: a potential therapeutic role in preserving cognitive function in age and neurodegeneration[J]. Gero Science, 2017, 39: 19–32.

[28] KETTENMANN H, HANISCH U-K, NODA M, et al. Physiology of microglia[J]. Physiol Rev 2011, 91: 461–553.

[29] LASRY A, ZINGER A, BEN-NERIAH Y. Inflammatory networks underlying colorectal cancer[J]. Nature Immunology, 2016, 17(3): 230–240.

[30] PAEK J, CHYUN J, KIM Y, et al. Astaxanthin decreased oxidative stress and inflammation and enhanced immune response in humans[J]. Nutrition & Metabolism, 2010, 7(1): 18.

[31] VOLKOVA M, RUSSELL R. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity: prevalence, pathogenesis and treatment[J]. Current Cardiology Reviews 2011, 7(4): 214–220.

[32] El-AGAAMY, S E, ABDEL-AZIZ, et al. Astaxanthin ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cognitive impairment (chemobrain) in experimental rat model: impact on oxidative, inflammatory, and apoptotic machineries[J]. Molecular Neurobiology, 2017, 55(7):5727–5740.

[33] BORLONGAN C, ACOSTA S, DE LA PENA I, et al. Neuroinflammatory responses to traumatic brain injury: etiology, clinical consequences, and therapeutic opportunities[J]. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 2015, 97.

[34] Ji X, PENG D, ZHANG Y, et al. Astaxanthin improves cognitive performance in mice following mild traumatic brain injury[J]. Brain Research, 2017, 1659: 88–95.

[35] TRIPATHI D N, JENA G B. Astaxanthin intervention ameliorates cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative stress, DNA damage and early hepatocarcinogenesis in rat: Role of Nrf2, p53, p38 and phase-II enzymes[J]. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis, 2010, 696(1): 69–80.

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese