Study on Natural and Synthetic Food Colours

Traditional Chinese food culture evaluates food from the three aspects of color, aroma and taste. People prefer food that looks good, and would not be attracted to a black tomato, red cucumber or food with poor color. In the past few decades, industrially produced food has become an important part of the diet. Tons of artificial and natural colors are consumed every day around the world [1]. Synthetic pigments have the advantages of being light and heat stable, having a high color value and being easy to mix, and have therefore been successfully used to color food, medicine and cosmetics. With the focus on healthy eating, there is a growing preference for natural pigments, which is leading to a wider market for them.

Although people can obtain pigments of various colors from thousands of plants, natural pigments are affected by the variety of the plant from which the pigment is derived, the cultivation conditions, the place of origin and the yield. Therefore, more and more research is devoted to discovering new sources of pigments to replace synthetic pigments, for example, tissue culture or genetic engineering [2]. Since the 1st International Food Color Conference held in Spain more than ten years ago, attention has been focused on the use of biotechnology to produce natural pigments. The 3rd International Food Color Conference, held in Tarbes, France, from June 14th to 17th, 2004, discussed the use of biotechnology to produce colorants [3]. The 6th International Food Color Conference, held in Budapest, Hungary, from June 20th to 24th, 2010, focusing on the three aspects of chemistry, biology and technology of food coloring [1]. In addition to tissue culture, the other two biotechnologies that can be used for pigment production are microbial fermentation and microalgae cultivation. This article lists the progress in the production and research of pigments using these three biotechnologies.

1 Microbial fermentation for pigment production

Microbial production of pigments is quite common in nature. For example, carotenoids, melanin, flavins, quinones and many more special pigments, such as red yeast rice pigments, violacein, phycocyanin and indigo. However, there is still a long way to go from the laboratory test stage to commercial large-scale production [4-5]. A long time ago, the Chinese used the red yeast rice in nature to make delicious food – fermented tofu – which has been passed down to this day. The red pigment produced by red yeast rice not only enhances the flavor of foods and stains fish products, but also has certain health benefits. Countries in Europe and the United States have restricted the use of red yeast rice pigment in foods due to the possible presence of citrinin during the production process.

1.1 Red yeast rice fermentation to produce pigment

The genus Monascus produces a complex mixture of pigments formed from three categories. The three colors are orange, red and yellow, and they are secondary metabolites of red yeast rice. Two polyketide precursor compounds are their precursor compounds. These secondary metabolites all have an azaphilone skeleton structure. The orange pigments include monascorubrin and rubropunctatin, which contain a lactone ring. The red pigments include monascorubramine and rubropunctamine, which are nitrogen-containing analogues of the orange pigments. The yellow pigments include monascin and ankaflavin (see Figure 1) [6]. Of these pigments, the red pigments (monascorubramine and rubropunctamine) are in the greatest demand, especially as a colour substitute for nitrite in meat products [7].

The fermentation of red yeast rice is generally carried out in a solid medium. Due to the low yield of inoculation in a solid medium, more and more research has focused on the production of red yeast rice pigments using liquid fermentation and submerged fermentation methods. Zhou et al. [6] used response surface analysis to select the optimal culture conditions for the production of yellow pigments, obtaining a 88.14OD yield in the shake flask system and a 92.45OD yield in the 5L fermenter system. Mukherjee [7] used submerged fermentation to cultivate red yeast rice to produce pigments, found a new pigment with the following structural characteristics (see Figure 2): -(1-hydroxyethyl)-3-(2-hydroxypropyl)-6a-methyl-9,9a-dihydrofuro[2,3-h]isoquinolin-6,8(2H,6aH)-dione, with a relative molecular mass of 375. It has many similarities with rubropunctamine and monascorubramine, but the hydroxylalkane substituents at C-3 and C-9 are different. In order to increase the production of red yeast rice pigment, Liu et al. [8] immobilized red yeast rice on a polyelectrolyte complex (PEC) coated with sodium cellulose sulfate and poly(dimethyl diallylammonium chloride). This microencapsulated form provided good conditions for the immobilization of the mycelium. The yield of red yeast rice cultivated in this microencapsulated form is three times that of the ordinary form, and its pigment yield is also twice that of the ordinary form.

1.2 Fermentation production of carotenoids

More than 600 carotenoids are known to occur in nature. Carotenoids are terpenoids with a polymeric conjugated double bond structure, which determines the light absorption characteristics of carotenoids, exhibiting colors from red to yellow [9-11]. Carotenoids are used as food additives not only because of their color characteristics, but also because they are functional substances. In the body, they are precursors for the synthesis of vitamin A and are important for human vision, preventing night blindness and dry eye. In addition, carotenoids have some antioxidant properties. All of this has contributed to the widespread use of carotenoids as food additives.

Carotenoids are divided into synthetic and natural carotenoids. Compared to each other, they have the same molecular structure and chemical and physical properties, but they have different biological effects. The synthetic β-carotene almost consists entirely of the all-trans isomer, while the natural product contains a significant amount of the cis isomer. In the body, the interaction of the various isomers in the natural product is an important guarantee of its biological function. Beta-carotene from certain microorganisms (such as Dunaliella salina) can contain up to 30% cis isomers [12]. Natural carotenoids have a wider range of food, medical and commercial value. Natural carotenoids can be efficiently obtained by fermenting basidiomycetes, such as microorganisms in the genus Rhodotorula, Torulopsis and Rhodotorula.

Aksu et al. [13] used Rhodotorula mucilaginosa as a carotenoid-producing strain and optimized the carbon and nitrogen sources, additives and molasses addition amount in the medium, resulting in a carotenoid yield of 35.0 mg/g dry cell weight. Liu Bing et al. [14] used red yeast as the production strain to study the effects of five growth factors on red yeast cell growth and carotenoid content. The results showed that peanut oil and riboflavin had a greater effect on biomass increase than tomato juice. The commercial production of β-carotene produced by the genus Dunaliella has been realized in Australia, Israel and the United States, while small-scale production has been carried out in Chile, Mexico, Iran and Taiwan, China, among other regions, have also produced it on a small scale [15]. Iriani [15] isolated carotenoids from yeasts in the Brazilian ecosystem. These pigments were mainly identified as cirrusin and β-carotene produced by the yeasts Rhodotorula glutinis, Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and Rhodotorula toruloides.

1.3 Fermentation production of melanin

Melanin is a kind of polyphenolic heteropolymer with a wide range of colors and applications. It is widely found in animals, plants and microorganisms. The physical and chemical properties of melanin give them many biological effects, including antioxidant properties, anticancer activity, antivenom activity, antiviral, hepatoprotective and anti-radiation, etc., and they are widely used in food, medicine and cosmetics and other fields [16]. Gu Minzhou [17] and others isolated a strain of Streptomyces antibioticus MV5002, a high melanin-producing strain, from the soil on the campus of Sichuan Normal University. after multiple optimizations of the culture, the yield reached 3.45 g/L. Shripad N. Surwase[18] and others isolated a high-yield black strain from the campus of Shivaji University in India. Phylogenetic tree inference suggested that it was a new bacterium, Brevundimouas sp. SGJ. After optimization by response surface analysis and intermittent addition of the melanin precursor lysine, its yield increased from the initial 0.401 g/L to 6.811 g/L. Ke Guanchun [19] and others isolated a strain with high yield of extracellular melanin from 321 strains of bacteria isolated from soil samples in the suburbs of Chengdu. The strain was identified as Streptomyces and with a yield of about 0.70 g/L. With the development and application of genetic engineering, effective genes can be transferred to more mature research strains such as Escherichia coli and Bacillus thuringiensis through recombinant engineering bacteria, which can facilitate and efficiently produce melanin.

Yali Huang[20] and others extracted DNA from microorganisms in deep-sea sediments in the South China Sea and cloned it in a Fuschia plasmid, producing 39,600 clones and an insertion site of 24–45 kb. Transferred into E. coli, it produced a reddish-brown pigment, which was identified as a type of melanin. Melanin can absorb ultraviolet light in the sun and protect the human body and microorganisms. Ruan Lifang et al. [21] cloned the melanin-producing gene (mel gene) from Pseudomonas maltophilia into the vector pHT3101, and transferred the constructed recombinant plasmid pHTAM into the Bacillus thuringiensis BMB171 receptor strain to to obtain the recombinant strain RSA. After optimization of the conditions, the yield of melanin reached 65 g/L, which is closely related to the pH value and substrate concentration in the environment.

Melanin produced by engineered bacteria also has biological effects. Li Xiaoyan et al. [22] used the quenching effect of melanin on the fluorescence intensity of benzoic acid hydroxylation products to compare the scavenging effect of melanin produced by the recombinant Bacillus thuringiensis pHTAM strain with that of standard melanin on hydroxyl radicals. The results showed that the recombinant bacterium had the ability to produce melanin to scavenge free radicals, which was comparable to Sigma's products and better than domestically produced commercial products extracted from living organisms. Ning Hua [23] studied the photoprotective effect of melanin produced by the genetically engineered bacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli)/P WSY on macromolecules. The results showed that the melanin produced by this engineered bacterium can significantly reduce ultraviolet damage to linear DNA molecules.

It is now known that a variety of bacteria, fungi and a few actinomycetes, such as Bacillus cereus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas maltophilia, Pseudomonas stutzeri, Nocardia nova, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus fumigatus, Pleurotus ostreatus, Auricularia auricula-judae, Cordyceps sinensis, Streptomyces, etc., have the ability to produce melanin. Since the culture conditions of some melanin-producing bacteria are not easy to control, more and more research is focusing on the construction of recombinant engineering bacteria. The genes that control melanin production are introduced into Escherichia coli and Bacillus thuringiensis to facilitate large-scale culture and thereby improve the yield and quality of melanin. The production of melanin by engineered bacteria has become a new trend.

1.4 Quinones and other pigments

Quinone pigments are not only good dyes, but also have very important medicinal value, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, anti-mutagenic and antibacterial. Quinone compounds are an important component of traditional Chinese medicine. Lou Zhihua [24] and others obtained anthraquinone pigments by fermenting the fungus Phellinus linteus, with a total yield of 1.72 mg/L. Hu Mingming [25] and others screened a strain of asexual Phellinus linteus from the wild Phellinus linteus stipe, and after optimizing the culture conditions, the pigment yield reached 2.795 g/L.

With the development of science and technology and the exploration of nature, people have discovered some unknown pigment-producing bacteria. Li Houjin [26] and others collected a strain of marine bacterium Pseudononas sp. from Daya Bay, and isolated two red pigments, pseudononas red A and dimethyl pseudononas red B, from this bacterium. They have strong antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties. As an important primary color, phycobilin can be mixed with red and yellow in different proportions to produce a variety of colors. Wen Lu [27] and others isolated a strain of marine bacterium Pseudononas sp. from the surface of seawater in the South China Sea. The fat-soluble fraction of the modified liquid medium was used to isolate a phycobilin with anticancer properties, Blue-1. Chen Minchun [28] and others optimized the culture conditions of the astaxanthin-producing strain CHU-R to obtain a high astaxanthin yield.

Since the discovery of microorganisms in the 17th century, many beneficial microorganisms have been effectively utilized, such as the use of microorganisms to produce antibiotics, quinones, alkaloids, peptides, anthraquinones, and food drugs. The secondary metabolites produced by microorganisms can be widely used in the fields of food, medicine, agriculture and petrochemicals. The production of safe and stable secondary metabolites – pigments – through microorganisms not only expands the sources of natural pigments, but also the yield and quality of pigments obtained in this way are relatively stable, which is quite popular with consumers and producers.

2 Tissue culture

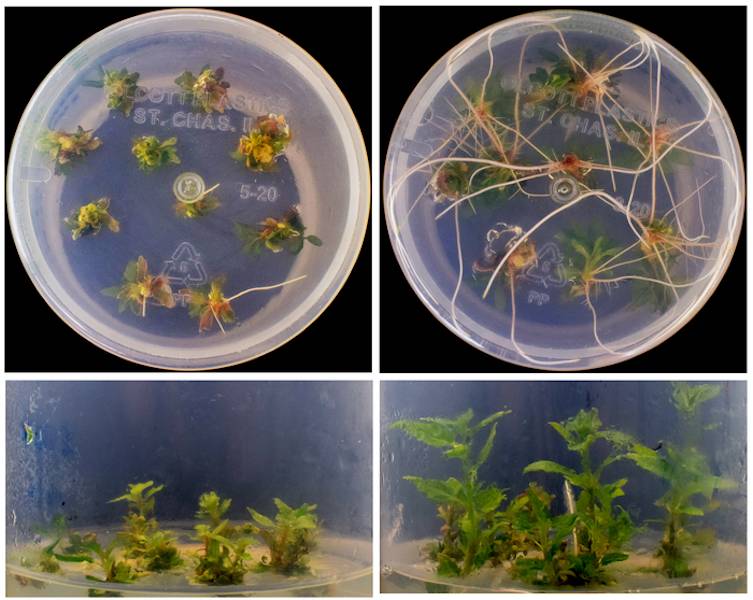

Plant tissue culture is based on the theory of the totipotency of plant cells. Plant tissues and cells are isolated and cultured under suitable culture conditions to grow, proliferate or regenerate into complete plants. It is used for anther and haploid culture, virus-free seedling cultivation, the establishment of rapid propagation systems, the production of secondary metabolites and the preservation of cells in vitro [29]. The formation of callus tissue through tissue culture and the search for suitable conditions to stimulate the production of secondary metabolites are an effective way to increase the production of natural pigments.

2.1 Tissue culture of gardenia and production of yellow pigment

Gardenia jasminoides is an evergreen shrub in the Rubiaceae family. Its fruit is a common Chinese medicinal herb and is rich in yellow pigment, the main component of which is crocin. Gardenia yellow pigment has a bright color, strong coloring power, good stability, and good water solubility. It has certain antibacterial and pharmacological effects and is a good food pigment that is widely used in food production. Gardenia grows slowly, taking three years to bear fruit, and its yield and quality are easily affected by growing conditions and the environment. Extracting gardenia yellow pigment from gardenia fruit can no longer meet the needs of industrial production. Using plant cell tissue culture technology to produce gardenia yellow pigment not only solves the problem of resource shortages, but is also not limited by natural conditions such as region and season, and has a relatively short production cycle. The study of gardenia tissue and cell culture for the production of gardenia yellow pigment is of great theoretical and practical significance [30].

In the 1990s, Zhong Qingping [30] and others optimized the conditions for the formation of gardenia callus tissue and the production of gardenia yellow pigment. The results showed that the B5 and MG-5 basic media were conducive to the growth of callus tissue. adding 0 to 1.5 mg/L indoleacetic acid (IAA) and 0 to 0.25 mg/L kinetin (KT) to the medium promoted callus growth and the production of yellow pigment. This study was one of the earliest in China. With the advancement of tissue culture technology, there has been an increasing number of studies on the production of secondary metabolites in gardenia and other plant tissue cultures.

Meng Zhiqing [31] used different parts of red gardenia, such as stem tips, stem segments and young leaves, as explants, and carried out culture experiments on three types of medium: MS, 1/2 MS and 1/4 MS. The results showed that the addition of 2.0 mg/L 2,4-D to the MS medium was the best condition for inducing callus tissue from red gardenia stem tips. Pan Qingping [32] and others conducted a preliminary study on the induction of Gardenia callus tissue. The hormone combination of NAA and 6-BA was found to be the most suitable for inducing callus tissue. However, no secondary metabolites, such as gardenoside, were produced, as detected by HPLC. Yoshihiko Nawa [33] and others used the seeds of fresh Gardenia jasminoides as explants using LS (Linsmaier-Skoog) + 1.0 mg/L IAA + 0.1 mg/L KT as the medium for subculture, and incubating in the dark for 32 generations (about 4 years), they obtained callus with dark yellow and orange colors.

Although the culture method of gardenia seed tissue is not affected by natural conditions such as climate and season, it takes a long time to obtain the target substance, and the operation requires a lot of manpower and material resources. How to improve the formation of gardenia callus tissue and the synthesis rate of gardenia yellow pigment by changing the culture conditions, adding precursors or inducers, etc., is the breakthrough point for the future industrial production of gardenia yellow pigment tissue culture.

2.2 Tissue culture of comfrey

Plants in the Boraginaceae family, such as those in the genera Euphorbia, Echinops, Euphorbia and Euphorbia, can produce euphorbia factor and its derivatives. Shikonin is a red pigment of the naphthol class that has antibacterial, antifungal, anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, anti-edematous, antitumor and wound-healing effects [34]. Gong et al. [35] believe that shikonin induces apoptosis in liver cancer cells through the ROS (reactive oxygen species)/Akt (protein kinase) and RIP1 (receptor-interacting protein)/NF-κB pathways, and may be a potential drug for the treatment of liver cancer. Chen Zhilu et al. [36] found that shikonin extracted from purple grass can effectively inhibit the proliferation of HL-60 cells from patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia and induce apoptosis. Shikonin can be used as an effective ingredient against leukemia. Shikonin is also a good color enhancer and is widely used in food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals.

The production of shikonin can be increased through tissue culture, enabling the commercial production of shikonin. The production of shikonin by tissue culture can be traced back to the 1960s. In 1983, the commercial production of shikonin by tissue culture became possible [37]. Yan Haiyan [38] used a two-stage culture method to study the effects of different culture media, hormone types, concentrations and nutrient compositions on the growth of callus tissue and the formation of alisol from comfrey. The results showed that the conditions of the culture medium suitable for the vegetative growth of callus tissue and the formation of alisol were different. The combination of B5 modified medium with 1.0 mg/L 6-BA and 0.1 mg/L IAA is suitable for the former, while the content of shikonin in the medium with CuSO4 is 3 times the concentration of M9. Using Agrobacterium rhizogenes to invade plants and induce root production can increase yield and reduce the addition of hormones.

Baranek et al. [39] used three strains of Agrobacterium rhizogenes ATCC15834, lba9402 and NCIB8196 to transform comfrey. After being cultivated in M9 medium for 32 days, all three types of hairy roots produced higher yields of comfrey derivatives, Among them, the amount of acetyl shikonin and isobutyryl shikonin increased by 4.7 times compared with the root-inoculated plant. Ashok [34] first used the wild-type strain A4 of Agrobacterium rhizogenes to mediate the induction of shikonin production in soft comfrey, optimizing the culture conditions. After 50 days of cultivation, the content of shikonin reached 0.85 mg/g fresh weight.

In 1983, the Japanese Mitsui Petrochemical Company used cultured comfrey for the first time to produce comfreyin. To date, cell culture research has been carried out on nearly 1,000 plant species worldwide. For example, nicotine is produced in tobacco cell tissue culture, paclitaxel in cell culture of yew, and anthocyanins in cell culture of roselle. Comfreyin, ginsenosides, and paclitaxel have already been produced industrially.

Extracting pigments from the seeds, rhizomes or leaves of plants is undoubtedly one of the most basic sources of natural pigments. However, natural pigments extracted in this way are not only susceptible to environmental and seasonal influences, but also expensive to produce, which is not conducive to their widespread use. The method of plant cell tissue culture can avoid the influence of the environment and season on pigment production, while also reducing the substantial costs of raw material collection and transportation during the production process. The use of plant tissue culture to achieve large-scale industrial production of target pigments also has multiple key control points that require technological breakthroughs, such as conditions optimization, long production cycles, and difficulties in scaling up fermentation.

3 Pigments produced by microalgae

Microalgae are a type of non-vascular plant that synthesize many valuable metabolites through photosynthesis, such as unsaturated fatty acids, proteins, microorganisms, pigments, etc., which can be widely used in food, medicine, textiles, and other fields. The pigments produced by the metabolism of marine algae are divided into three categories: red, green, and brown, which are produced by algae belonging to the families of Rhodophyta, Chlorophyta, and Phaeophyta, respectively. Chlorophyll, carotenoids and phycobiliproteins are the three classic pigments produced by marine algae [40]. As the biological activity and antioxidant properties of pigments synthesized by microalgae have been proven, these pigments are expected to have a wider range of applications in the fields of food, medicine and textiles. There are many types of carotenoids derived from microalgae (Table 1) [41].

Astaxanthin (3,3′-dihydroxy-β,β-carotene-4,4′-dione) is a keto-type carotenoid that is not a source of microbial A. Its molecular formula is C40H52O4 and its structure is shown in Figure 3. Astaxanthin is a pink needle-like crystal with a luster, melting point 216 °C, insoluble in water, soluble in organic solvents such as carbon disulfide, acetone, benzene and chloroform [42]. Astaxanthin has strong antioxidant properties, is an effective photoprotectant, can prevent atherosclerosis and related diseases, has certain anticancer properties, can enhance the function of the body's immune system and maintain the health of the eyes and central nervous system, and can be used in a variety of animal feeds. Compared with synthetic pigments of the same concentration, astaxanthin, as a natural food pigment, has much higher coloring power and biological potency[43].

Natural astaxanthin is mainly derived from microalgae, bacteria, fungi and processed waste from crustaceans. Haematococcus pluvialis can accumulate a large amount of astaxanthin. In addition, green algae such as Chlorella, Scenedesmus, Dunaliella and Nannochloropsis will also accumulate more or less astaxanthin under adverse environmental conditions. Red yeast, dark red yeast and sticky red yeast can also produce astaxanthin. Dong Qinglin [42] mixed the cultures of Haematococcus pluvialis and Rhodopseudomonas palustris to take advantage of the synergistic effect of the two to increase the biomass of the red algae and the astaxanthin production. Cai Ying [44] used ultraviolet (UV), ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS), nitrilotriacetic acid (NTG), etc. as mutagens to screen for mutant strains with high astaxanthin production. Haematococcus pluvialis is more likely to produce astaxanthin under adverse growth conditions (e.g. high temperatures, dryness, strong light, high salinity, etc.).

Esra [45] and others investigated the accumulation of astaxanthin produced by Haematococcus pluvialis in four types of culture medium and two light intensities. The results showed that astaxanthin accumulated more quickly in a culture medium with CO2-enriched distilled water. These simple culture conditions are conducive to large-scale industrial production, while the use of two light sources had no effect on astaxanthin accumulation.

Tomo- hisa[46] and others studied the effects of flashing blue diode light and continuous light on the growth of Haematococcus pluvialis and astaxanthin accumulation. The results showed that flashing light photos accumulated higher astaxanthin concentrations than continuous light. The concentration of astaxanthin accumulated was higher under the conditions of distilled water with added CO2 and flashing blue diode light. The culture conditions are simple and energy-saving, suitable for industrial production. Phycobiliproteins are also a natural pigment produced by algae metabolism. Phycobiliproteins produced by algae metabolism were discovered as early as the last century. Now, more research is being done on how to extract phycobiliproteins from algae, so I won't go into detail here.

Microalgae can produce secondary metabolites through the photosynthetic pathway. Compared to the former, adding fewer hormones and carbon sources during the cultivation of microalgae can save energy for large-scale industrial production.

Although synthetic pigments have high yields, are stable in nature and have a bright color, their potential safety issues are gradually fading out of the food additive market, and natural pigments have become the new favorite of the food industry. At present, major companies around the world are doing their utmost to compete for a share of the natural coloring market. Japan has long dominated the production of red yeast rice pigment, while Europe and the United States are also strong players in the production of algal pigments and carotenoids. The production of natural pigments in China relies more on the extraction of plants themselves. Although the output is relatively high, it is susceptible to the influence of uncertain factors in the natural environment, which inevitably results in higher economic costs.

Reference:

[1] Agδcs A. Pigments in your food[J]. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis ,2011 ,24 :757-759.

[2] Beno↑t S. Determination of pigments in vegetables[J]. Journal of Chromatography A ,2004 , 1045 :217-226.

[3] Dufoss6 L. Pigments in food ,more than colours[J]. Trends in Food Science & Technology ,2005 , 16 :368-369.

[4] Dufoss6 L , Galaup P ,Anina Y,et al. Microorganisms and microalgae as sources of pigments for food use a scien- tific oddity or an industrial reality[J]. Trends in Food Science & Technology ,2005 , 16(9):389-406.

[5] Zhang Yan, Zhang Lili, Tong Qigen. Extraction and separation of paprika red [J]. Journal of Beijing Technology and Business University: Natural Science Edition, 2011, 6: 45-49

[6] Zhou B , Wang JF , Pu YW , et al. Optimization of culture medium for yellow pigments production with Monascus anka mutant using response surface methodology[J]. European Food Research and Technology ,2009 ,6(228): 895- 901.

[7] Mukherjee G , Singh S K. Purification and characterization of a new red pigment from Monascus purpureus in sub- merged fermentation[J]. Process Biochemistry ,2011 ,46: 188-192.

[8] Liu JF , Ren YR , Yao SJ. Repeated-batch cultivation of encapsulated Monascus purpureus by polyelectrolyte com- plex for natural pigment production[J]. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering ,2010 , 18(6): 1013-1017.

[9] Santipanichwong R ,Suphantharika M. Carotenoids as colorants in reduced-fat mayonnaise containing spent brewer ’s yeast β-glucan as a fat replacer[J]. Food Hydrocolloids ,2007 ,21 :565-574.

[10] Wang Cheng, Chen Yulong, Xu Yujuan, et al. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging with ultra-high oxygen and high barrier film on the quality of fresh-cut carrots [J]. Journal of Beijing Technology and Business University: Natural Science Edition, 2012, 3: 59-64

[11] Chen Chen, Zhao Wei, Yang Ruijin. Effect of high-voltage pulsed electric field on the quality and endogenous enzyme activity of freshly squeezed carrot juice [J]. Journal of Beijing University of Industry and Commerce: Natural Science Edition 2011, 3: 28-32

[12] Huibodi, Li Jing, Pei Lingpeng. Production and application of carotenoids in China's food industry [J]. China Food Additives, 2006, 3: 130-135.

[13] Aksu Z , Eren T A. Carotenoids production by the yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa: Use of agricultural waste as a carbon source[J]. Process Biochemistry ,2005,40:2985-2991.

[14] Liu Bing, Xin Jiaying, Zhang Shuai, et al. Selection of carotenoid-promoting factors produced by red yeast [J]. Agricultural Products Processing, 2011, 10: 17-20.

[15] Maldonade I R , Delia B. Rodriguez -Amaya , Adilma R.P. Scamparini. Carotenoids of yeasts isolated from the Brazilian ecosystem[J]. Food Chemistry ,2008 , 107: 145-150.

[16] Dong Caihong , Yao Yijian. Isolation , characterization of melanin derived from Ophiocordyceps sinensis , an en- tomagenous fungus endemic to the Tibetan Plateau[J].Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2012 , 113(4):474- 479

[17] Gu Minzhou, Huang Min. Screening and cultivation of a high-yield melanin-producing strain and preliminary research on melanin [D]. Chengdu: Sichuan Normal University, 2006.

[18] Shripad N. Surwase , Shekhar B. Jadhav , Swapnil S. Phugare , et al. Optimization of melanin production by Bre- vundimonas sp. SGJ using response surface methodology[J]. Biotech ,2013 ,3(3): 178-194

[19] Ke Guanqun, Chunze, Wanbo, et al. Isolation and identification of high-yielding melanin-producing strains [J]. Journal of Applied and Environmental Biology, 2005, 11(6): 760-762.

[20] Huang Yali ,Zhou Shining ,et al. Characterization of a deep-sea sediment metagenomic clone that produces water- soluble melanin in Escherichia coli[J]. Mar Biotechnol. 2009 , 11: 124-131.

[21] Ruan Lifang, Wang Yujie, Shen Ping. Construction of a recombinant strain of B. thuringiensis that produces melanin and optimization of its culture conditions [J]. Journal of Wuhan University: Science Edition, 2003, 49(2): 257-260.

[22] Li Xiaoyan, Liu Zhihong, Wang Peng, et al. Research on the antioxidant effect of melanin produced by engineered bacteria [J]. Journal of Wuhan University: Science Edition, 2003, 49(6): 693- 696.

[23] Ning Hua. Research on the photoprotective effect of melanin produced by engineered bacteria on biological macromolecules [J]. Journal of Central China Normal University: Natural Science Edition, 2001, 35(1): 85- 88.

[24] Lou Zhihua, Shi Guiyang. Fermentation of anthraquinone pigments by medicinal fungus Phellinus igniarius and study of their structures [D]. Wuxi: Jiangnan University, 2006.

[25] Hu Mingming, Cai Yujie, Liao Xiangru, et al. Liquid fermentation and separation and purification of perylenequinone pigments [D]. Wuxi: Jiangnan University 2012.

[26] Li Houjin, Cai Chuanghua, Zhou Yipin, et al. The red pigment in the Daya Bay marine bacterium Pseudononas sp. Zhongshan University Journal: Natural Science Edition, 2003, 42 (3): 102-104.

[27] Wen Lu, Yuan Baohong, Li Houjin, et al. A blue pigment produced by marine bacteria Pseudomonas sp. from the South China Sea with antitumor activity [J]. Journal of Sun Yat-sen University: Natural Science Edition, 2005, 44(4): 63-69.

[28] Chen Minchun, Liao Meide. Identification of astaxanthin-producing strain CHU-R and optimization of its culture conditions [J]. Journal of Northwest A&F University: Natural Science Edition, 2012, 40(6): 153-160.

[29] Yang Shushen. Cell Engineering [M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2009.

[30] Zhong Qingping, Yang Ningsheng, Chen Mihui. Study on the factors influencing the growth of Gardenia jasminoides callus and the synthesis of yellow pigment. Journal of Nanchang University: Science Edition, 1994, 3

(18): 256-262.

[31] Meng Zhiqing. Study on the induction of callus in Gardenia jasminoides. Anhui Agricultural Science, 2007, 35(20): 6044, 6332.

[32] Pan Qingping, Wang Qingbo, Li Lin, et al. Preliminary study on the induction of callus tissue from Gardenia jasminoides Ellis. Chinese Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2009, 34(11): 1451-1453

[33] Yoshihiko Nawa ,Toshio Ohtani. Induction of Callus from flesh of Gardenia jasminoides ELLIS fruit and formationof yellow pigment in the callus[J]. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. , 1992 ,56(11): 1732-1736.

[34] Chaudhury A , Minakshi P. Induction of shikonin production in hairy root cultures of Arnebia hispidissima via Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated genetic transformation[J]. The Korean Society of Crop Science ,2010 , 13(2):99- 196.

[35] Gong K ,Li WH. Shikonin ,a Chinese plant-derived naphthoquinone ,induces apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through reactive oxygen species :A potential new treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Free Radical Biolo- gy and Medicine ,2011,51(12):2259-2271.

[36] Chen ZL, Dai QZ, Wang Y, et al. Effect of shikonin on proliferation and apoptosis of leukemia cell HL-60 [J]. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine, 2012, 32(2): 239-243.

[37] Jin CZ. Research progress in the preparation of shikonin [J]. Jiangsu Food and Fermentation , 2006 , 2: 16-20.

[38] Yan Haiyan, Cao Riqiang. Influencing factors of shikonin formation in callus culture of purple grass [J]. Journal of North China Agricultural University, 2007, 17(2): 116-120.

[39] Baranek KS ,Pietrosiuk A ,Gawron A ,et al. Enhanced production of antitumor naphthoquinones in transgenic hairy root lines of Lithospermum canescens[J]. Plant Cell ,Tissue and Organ Culture ,2012 , 108(2): 213-219.

[40] Ratih Pangestuti ,Se-kwon Kim. Biological activities and health benefit effects of natural pigments derived from ma- rine algae[J]. Journal of functional foods ,2011 ,3(4):255-266.

[41] Wu Jilin, Zhou Bo, Ma Pengyou, et al. Research progress of microalgal pigments [J]. Food Science, 2010, 31(23): 395-400.

[42] Dong Qinglin and Zhao Xueming. Using the synergistic effect of the metabolic processes of Haematococcus pluvialis and Rhodopseudomonas palustris to increase astaxanthin production [D]. Tianjin: Tianjin University, 2004.

[43] Wei Dong and Yan Xiaojun. Super-antioxidant activity of natural astaxanthin and its application [J]. Chinese Journal of Oceanic Drugs , 2001 , 4 : 45-50.

[44] Cai Ying, Gao Jing, Dong Qinglin. Breeding and spectral analysis of high-yield astaxanthin Haematococcus pluvialis [D]. Tianjin: Hebei University of Technology, 2009.

[45] Imamoglu E , Dalay MC , Sukan FV. Influences of different stress media and high light intensities on accumulation of astaxanthin in the green algae Haematococcus pluvialis[J]. New Biotechnology ,2009 ,26(3): 199-204.

[46] Katsuda T,Shimahara K , Shiraishi H,et al. Effect of flashiing light from blue emitting diodes on cell growth and astaxanthin production of Haematococcus pluvialis[J].The Society for Biotechnology ,2006 , 102(5):442-446.

-

Prev

The Character and Types of Natural Food Coloring

-

Next

Food Freshness Indicator Packaging with Natural Coloring

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese