Study on Bio Synthesis of Mogroside V

Sweeteners are a type of food additive. They can be divided into synthetic sweeteners and natural sweeteners according to their source. Natural sweeteners can be further divided into saccharides and non-saccharides according to their chemical structure and properties. Recent studies have pointed out that synthetic sweeteners can lead to intestinal flora imbalance and glucose intolerance, causing metabolic disorders[1], and have become a new type of pollutant causing environmental pollution[2]; while the high intake of sugar contributes to the occurrence of dental caries, obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease[3-5]. Natural non-sugar substances of plant origin have attracted increasing attention as a new generation of sweeteners that can satisfy sweet cravings due to their high sweetness [6], low calories [7], safety [8], and lack of cariogenicity [9].

At present, the main natural non-sugar sweeteners that have been developed and utilized at home and abroad are: Thaumatin, steviol glycosides, Mogroside (Mogrosides) and glycyrrhizic acid[6] (Table 1), among which the sweetest is Thaumatin, but it exhibits a bitter taste and the “off-flavor” of liquorice, and has the disadvantages of delayed sweetness and an excessively long duration [17]; the second is monk fruit sweetener, which has no unpleasant aftertaste and is the only all-natural sweetener that can reduce fat [14]. Mogroside V (M5) is the main source of the sweetness of Mogroside [18]. At a concentration of 1/10,000, its sweetness value is 425 times that of 5% sucrose [19]. It also has many pharmacological activities, such as relieving coughs and phlegm [20], anti-cancer [21-22], anti-oxidation [23], and many other pharmacological activities, making it a new generation of functional sweeteners that are being developed around the world. Due to the many difficulties involved in cultivating Luo Han Guo [25], and the fact that the content of M5 in the whole fruit is only 0.8%–1.3% (W/W) [26], it is difficult to purify the complex product of its analogues, and it is impossible to achieve large-scale production by relying on extraction from Luo Han Guo.

The development of plant cell culture [27], metabolic engineering [28] and synthetic biology [29] has provided sustainable production ideas for the acquisition of natural plant products. Plant cell culture is difficult to use to produce specialized natural products due to its high cost, long time-scale, and low yield. In addition, the complexity of plant cells and the lack of genetic tools and appropriate methods make metabolic engineering of plant cells challenging for the production of complex natural products M5, which require multi-step biosynthesis pathways [30]. Therefore, plant cell culture and metabolic engineering may not be a viable method for the large-scale production of M5. Synthetic biology is a science that has emerged in recent years to redesign, engineer, construct, and apply life systems and processes [31].

Compared with traditional methods, it has the advantages of short cycle, high yield, safety and no pollution, and simple extraction process. It is a new green and efficient production model. With the continuous development of synthetic biology research and an in-depth understanding of the molecular biosynthesis mechanism of mogrosides in Luo Han Guo [32], the use of microorganisms to synthesize M5 has become a new way of large-scale production, which is of great significance and broad prospects in meeting consumer demand for natural sweeteners. This paper focuses on a review of the biosynthesis mechanism and synthetic biology research progress of M5, and discusses the challenges faced in microbial synthesis, with a view to providing a reference for the biosynthesis research of M5.

1 Structure and pharmacological activity of Mogroside V

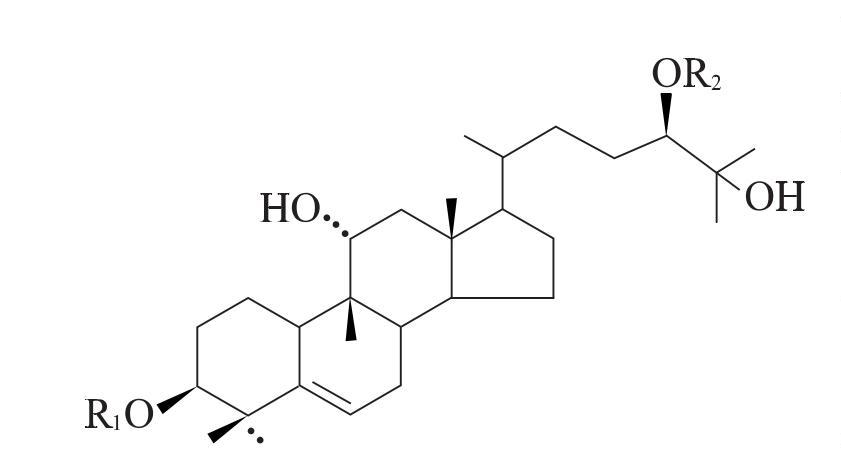

Siraitia grosvenorii is the ripe fruit of the Siraitia grosvenorii plant in the Cucurbitaceae family. It is used as a common traditional Chinese medicine in China [33] for its effects of moistening the lungs to relieve coughs, cooling the blood, and moistening the bowels to promote bowel movements. Its main active ingredient is the sweet glycoside [34]. Researchers [19,35–36] have isolated and identified a variety of sweet glycosides in Siraitia grosvenorii, the basic structure of which is shown in Figure 1. The number of glucose units and the way they are connected produce sweetener molecules with significantly different tastes: the disaccharide sweetener IIE tastes extremely bitter, while the pentasaccharide M5 tastes extremely sweet [37].

M5 is the component of the Luo Han Guo sweetener with the highest sweetness and content [38]. It was first isolated by Japanese scholars such as Takemoto Tsunematsu [39-41], and the structure of the aglycone was identified as the tetracyclic triterpene momordinol by spectroscopic methods, thereby constructing the complete structure of M5. The molecular formula of M5 is C60H102O29, which is formed by adding glucose units to momordinol at the C3 and C24 positions. R2 is two pyranose units linked by a β-1,6-glycosidic bond, R1 is a branched 3-glucopyranosyl group linked by β-1,6-glycosidic bonds and β-1,2-glycosidic bonds.

Natural non-sugar sweeteners of plant origin often exhibit multiple pharmacological activities (Table 1). M5 has many functions, including relieving coughs and phlegm, anti-cancer, anti-oxidation, and regulating blood sugar. Studies have shown that the active ingredient in Luohanguo that relieves coughing is 50% alcohol extract by volume, and the isolated M5 can significantly reduce the number of coughs in mice, prolong the cough latency period, and significantly increase the excretion of phenol red in the trachea, indicating a certain expectorant effect [20]. M5 can inhibit the proliferation and survival of pancreatic cancer cells by targeting multiple biological targets [21], which was confirmed in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer xenografts. 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA), 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and peroxynitrous acid (ONOO–) are carcinogens that induce the transformation of normal cells into tumour cells. M5 was found to slow the transformation of normal cells into skin cancer cells by antagonizing carcinogens in a mouse skin carcinogenesis test [22], indicating that M5 has the effect of preventing skin cancer caused by chemical carcinogens. M5 and 11-O-mogroside V can significantly scavenge reactive oxygen species (O2–·, H2O2 and ·OH) and inhibit oxidative DNA damage. whereas 11-O- Mogroside V has a higher scavenging effect on O2– · and H2O2 than M5, but M5 has a better scavenging effect on ·OH [23]. It was found that M5 can induce insulin secretion in the insulinoma cell RIN-5F, thus revealing the blood glucose regulating effect of M5 on the cellular level for diabetic patients. This study suggests that Luo Han Guo extract, especially M5, has the potential to prevent and treat type 2 diabetes [24].

2. Research on the biosynthesis mechanism of Mogroside V

Synthetic biology is the reconstruction of existing biosynthesis pathways in microbial cells [29] to obtain microbial cell factories that produce desired products, thereby achieving large-scale production of target compounds. Therefore, clarifying the molecular mechanism of M5 synthesis in Luo Han Guo will lay the foundation for using synthetic biology to construct cell factories and achieve in vitro synthesis.

2.1 Accumulation pattern of Mogroside

Understanding the accumulation pattern of Mogroside is conducive to a better analysis of the molecular mechanism of M5 synthesis. Research on the accumulation pattern of Mogroside during the development of Luohanguo has shown that the net content of Mogroside is conserved, that is, the total content of Mogroside remains unchanged throughout the growth process [42]. During the early stages of fruit development, the glycosides are mainly in the form of Mogroside IIE, with R1 and R2 both being monosaccharide groups. This indicates that the early step in the glycosylation of the glycosides is two primary glycosylations, after which the second glycosyl group is linked to R1 by a β-1,6-glycosidic bond, resulting in the accumulation of mogroside IIIX. At a later stage (77 d after flowering), a large number of tetrasaccharide products appeared, mainly sialenoside (Siamenoside), whose R1 contains a branch formed by a β-1,6-glycosidic bond and a β-1,2-glycosidic bond. The consumption of tetrasaccharide products began 77 days after flowering, and accumulation of R2 M5, which contains two sugar moieties, increased sharply during the final stage of maturation. The main component of the sweet glycoside in mature fruits 103 d after flowering is M5. The accumulation pattern of mogroside suggests that the biosynthetic pathway of M5 is that mogroside first undergoes primary glycosylation at the C3 and C24 positions, and then branched glycosylation is carried out on this basis [32].

2.2 Mogroside V biosynthesis pathway analysis

Transcriptome and metabolome analysis is an effective strategy for elucidating the biosynthesis pathways of plant natural products [43]. In 2016, Israeli researchers Itkin et al. [32] achieved a complete analysis of the M5 biosynthesis pathway based on the transcriptome and genome data of Luo Han Guo (Fig. 2). The M5 biosynthesis pathway can be roughly divided into three stages: the upstream precursor synthesis stage, the midstream skeleton formation stage, and the downstream parent nucleus production and modification stage.

2.2.1 Synthesis of precursors IPP and DMAPP

The upstream precursors for terpene synthesis include isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). There are two different pathways for the biosynthesis of IPP and DMAPP in plants: the mevalonic acid pathway (MVA pathway) and the mehyl-erythritol phosphate pathway (MEP pathway). The choice of different pathways depends on the type of synthetic product and subcellular spatial location [45]. The MEP pathway is mainly used for the synthesis of monoterpenes, diterpenes and tetraterpenes in plastids [46], while the MVA pathway is mainly used for the synthesis of sesquiterpenes, triterpenes and polyterpenes in the cytoplasm [47]. However, the two are not completely independent, and the common intermediate IPP can be used by each other through the plastid membrane [48].

M5 is a triterpene saponin product in the cytoplasm, and its precursors IPP and DMAPP are generated from acetyl coenzyme A via the MVA pathway. First, two molecules of acetyl coenzyme A are formed from acetyl coenzyme A thioesterase (ATOT) and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A synthase (HMGS) to form 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA). Then, under the catalysis of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGR), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (MVA) is formed, which is then converted into IPP by the enzymes methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate kinase (MK), methyl-D-erythritol-3-phosphate kinase (PMK) and methyl-D-erythritol-3-phosphate decarboxylase (MVD). IPP is converted into its double-bonded isomer, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), by the enzyme isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase (IPI).

2.2.2 Formation of the skeletons 24,25-epoxygulldienol

Geranyl pyrophosphate synthase (PS) catalyzes the formation of geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) from IPP and DMAPP. Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FPPS) then catalyzes the synthesis of farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) from one molecule of IPP. FPP is converted into squalene (SQ) by squalene synthase (SQS). SQS is a bifunctional enzyme that first catalyzes the condensation of two FPP molecules to form pre-squalene diphosphate (PSPP), and then converts PSPP to SQ in the presence of NADPH and Mg2+[44].

For a long time, scientists believed that squalene epoxidase (SQE) catalyzed the one-step reaction of SQ to form the linear 2,3-epoxysqualene, which was then cyclized by the cyclase to form the skeleton substance, ulipristal[49]. However, recent studies have shown that the precursor of the aglycone is 24,25-epoxylup-20(29)-en-3-ol, not cucurbitadienol, and that the precursor is 2,3;22,23-diepoxysqualene, not 2,3-epoxysqualene. SQ undergoes two consecutive epoxidation reactions catalysed by SQE, in order, producing 2,3-epoxysqualene, 2,3;22,23-dioxosqualene, and the latter being cyclized to 24,25-epoxygulustrenol under the catalysis of cucurbitadienol synthase (CDS) [32].

2.2.3 Production and modification of the parent nucleus, mogroside

The unique feature of the cucurbitane tetracyclic triterpenoid Mogroside is the region-specific oxygenation at the C3, C11, C24 and C25 positions (Figure 2), forming the parent nucleus mogroside [32]. Therefore, the main challenge in identifying the step of mother nucleus synthesis is its unique hydroxylation, especially the trans-hydroxylation of the C24 and C25 positions. Itkin et al. [32] found that the epoxide hydrolase (EPH) is responsible for catalyzing the hydroxylation of the C24 and C25 positions of 24,25-epoxylup-20(29)-en-3-one to to generate trans-24,25-dihydroxylup-20(29)-en-3-one, which is then hydroxylated at the C11 position by a member of the CYP87 family, CYP87D18 (CYP102801),[50] in the cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP450) system to generate lupeol. The order of the hydroxylation reactions has also been proposed: The EPH protein tends to bind to epoxylup-20(29)-en-1-ol rather than the linear 2,3;22,23-diepoxysqualene, so the EPH reaction follows the CDS cyclization reaction; the additional hydrophilic hydroxyl group on C11 would prevent docking in the EPH hydrophobic pocket, so the C11 hydroxylation reaction occurs after the EPH reaction.

The final step in the synthesis of M5 is the glycosylation modification of the C3 and C24 positions of mogroside. It was found that glycosylation at the C24 position increases the affinity for glycosylation at the C3 position by docking the substrate with the glycosyltransferase. The order of glycosylation was determined based on the accumulation pattern of Mogrosides: Mogroside first undergoes primary glycosylation at the C24 position by glycosyltransferase UGT720-269-1 to to generate mogroside Ⅰ-A1; the latter is then glycosylated at the C3 position by UGT720-269-1 to generate mogroside ⅡE; subsequently, UGT94-289-3 is responsible for branched glycosylation of the glucose chain at the C3 and C24 positions, and the tetrasaccharide intermediate is synthesized to form M5[32].

3 Mogroside V Synthetic biology preliminary research

As a natural non-sugar sweetener, the microbial production of the protein sweetener taro sweetener has a long history of research, and has been achieved in a variety of microorganisms [51-53], but the yield is low. The biosynthetic pathway of stevioside was completely elucidated in 2013 [54]. At present, the fermentation and synthesis of stevioside products have been reported, mainly including rebaudioside A, rebaudioside D and rebaudioside M [55-56], but the yield is low, because the constructed synthetic pathway is relatively long.

In 2016, Xu et al. [57] reported UDP-glucuronic acid transferase GuUGAT (belonging to the UGT73 family) from licorice, which catalyzes the two-step glucuronic acid glycosylation of glycyrrhizic acid to form glycyrrhizic acid, thereby revealing the complete pathway of glycyrrhizic acid biosynthesis. Professor Li Chun's research group [58] used an engineered bacterium that produces glycyrrhizic acid as a basis and introduced the human glycosyltransferase UGT1A3 gene, the human UDP-glucose dehydrogenase UGDH (Hs) gene, and the Escherichia coli-derived UGDH (Ec) gene to obtain a recombinant bacterium that produces glycyrrhizic acid. Due to the late elucidation of the biosynthetic pathway of Mogroside and the long pathway, research on the synthetic biology of M5 is limited.

3.1 Selection and optimization of chassis cells

Chassis cells are factories for the synthesis of natural products. The selection of chassis cells with mature operating systems and genetic stability is the basis for the efficient production of natural products. The model microorganisms Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are often used as chassis cells. Saccharomyces cerevisiae has unique advantages in the research of heterologous synthesis of complex natural products such as M5: the endogenous MVA pathway and ergosterol synthesis pathway can stably provide precursors IPP, DMAPP and 2,3-epoxy-squalene [59-60], and the complete membrane system and post-translational modification are conducive to the active expression of cyclase and CYP450. 2,3-epoxysqualene is a common precursor for the synthesis of the triterpenoid and sterol skeletons in plants [61]. However, in the biosynthesis of sweeteners, the precursor for skeleton synthesis is 2,3;22,23-diepoxysqualene. The endogenous squalene epoxidase (ERG1) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae can oxidize 2,3-epoxysqualene to 2,3;22,23-bisepoxysqualene [32,62], which means that the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ERG1 can replace SgSQE.

Most of the 2,3-epoxysqualene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells enters the ergosterol synthesis pathway via lanosterol synthase (ERG7) [63], competing for the metabolic flow to mogroside conversion. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain GIL77 accumulates high concentrations of 2,3-epoxysqualene due to the lack of ERG7 [64] and is often used as a chassis cell to verify the function of enzymes related to mogroside synthesis. With the continuous development of biological research on triterpene saponin synthesis, strategies for optimizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae to accumulate large amounts of 2,3-epoxysqualene have gradually been improved. mainly the following: 1) overexpression of genes related to terpene synthesis in the MVA pathway [65-66]; 2) inhibition of ergosterol synthase using the inhibitor R0 48-8072 or the CRISPR/dCas9 system to inhibit the expression of ERG7 [32,63], downregulate the ergosterol synthesis branch; 3) use the mutant gene upc2-1 of the global transcription factor UPC2 to directly or indirectly upregulate the transcription efficiency of genes related to the MVA pathway [67].

3.2 Cloning and expression of key enzyme genes

To achieve de novo synthesis of M5 in microbial cells, the key enzyme genes need to be heterologously assembled. Therefore, the cloning of enzyme genes will provide the parts for heterologous assembly, and the heterologous expression of enzymes will lay the foundation for functional research. The key enzymes that have been cloned and expressed so far are SQE, CDS, EPH, CYP450 and glycosyltransferase.

3.2.1 Squalene epoxidase

Squalene epoxidase performs the double epoxidation of squalene, which has been reported in many triterpenoid synthase systems [68–70], and functionally expressed plant squalene epoxidase can simultaneously produce mono- and di-oxidized squalene [62,71]. In 2018, Zhao Huan et al. [72] cloned two full-length fragments annotated as SQE genes from Luo Han Guo, both containing a complete open reading frame of 1,575 bp encoding 524 amino acids, and named them SgSQE1 and SgSQE2, respectively. Since the N-termini of the protein sequences encoded by SgSQEs both have transmembrane domains, they exist as inactive inclusions when expressed in prokaryotes, and enzyme activity cannot be verified. Molecular docking of the protein substrate indicates that SgSQEs can interact with the ligand 2,3-epoxysqualene to form hydrogen bonds, and it is speculated that they may have the function of generating bis-epoxysqualene. Later, Itkin et al. [32] modeled the SgSQE protein and showed that the presence of the first epoxide did not prevent the docking of the second epoxidation, indicating that SgSQE can undergo a double epoxidation reaction.

3.2.2 Cucurbitadienol synthase

2,3-epoxysqualene is formed by protonation, cyclization, rearrangement and deprotonation under the catalysis of different types of oxidosqualene cyclase (OSC), which forms the skeleton of phytosterols and triterpenes [73]. Therefore, there is competition between different types of OSC. As a member of the OSC family, CDS is a key cyclase in the synthesis of mogrosides. Its expression and activity affect the metabolic flow of the conversion of 2,3-epoxysqualene to mogroside, which determines the yield of mogrosides.

Dai et al. [74] identified SgCDS through RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and digital gene expression profiling (DGE) analysis of Luo Han Guo. The cDNA is 2,800 bp in length and contains an ORF of 2,280 bp, encoding a protein with 759 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 84.4 kDa. The cyclization function of SgCDS was subsequently verified using the yeast strain GIL77, which can cyclize 2,3-epoxysqualene to cucurbitadienol. This seems to be inconsistent with the SgCDS in the biosynthetic pathway of Mogroside cyclizing 2,3;22,23-diepoxysqualene to generate 24,25-epoxy-squalene (Figure 2). In fact, Itkin et al. [32] used Saccharomyces cerevisiae and transformed tobacco Nicotiana tabacum L to functionally analyze SgCDS and found that SgCDS can not only cyclize 2,3;22,23-bisepoxysqualene, but also cyclize 2,3-epoxysqualene to produce squalene, although the latter is not involved in the synthesis of Mogroside. Further studies have shown that for 2,3-epoxysqualene, the cyclization of SgCDS precedes the epoxidation of ERG1, making SgCDS mainly exhibit the cyclization function of 2,3-epoxysqualene.

3.2.3 CYP450 and glycosyltransferase

CYP450 is a superfamily of genes in plants that play a key role in the oxidation of natural products such as terpenes, flavonoids, alkaloids and lignin [75]. with strict substrate specificity and low sequence similarity. Glycosyltransferases may be members of the second largest plant enzyme family 1UGTs, which transfer different sugars or sugars to different receptors, and require different glycosyltransferases [76]. Therefore, it is relatively difficult to efficiently discover and clone CYP450 and glycosyltransferase genes that catalyze the biosynthesis of specific metabolites. Tang et al. [77] identified and screened seven CYP450s and five UDPGs as candidate genes responsible for the synthesis of M5 based on the combined application of RNA-seq and DGE, combined with the rapid accumulation of M5 after 50–70 d after flowering. This method has created an effective way to identify candidate genes responsible for the biosynthesis of novel secondary metabolites in non-model plants.

Zhang et al. [50] identified a multifunctional cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP87D18) and a glycosyltransferase (UGT74AC1) in Luo Han Guo. In vitro enzyme activity assays showed that CYP87D18 is responsible for catalyzing the oxidation of the C11 position of the furostanol to form 11-oxofurostanol and 11-hydroxyfurostanol; UGT74AC1 can specifically transfer glucose to the C3 position of the loganinol to form loganin IE. Almost at the same time, Itkin et al. [32] identified 191 CYPs and 131 UGTs in Momordica grosvenori, and preliminarily screened 40 CYPs and 100 UGTs that were expressed in developing fruits. Functional verification was carried out in yeast and Escherichia coli, respectively. The results showed that CYP87D18 (CYP102801) catalyzes the hydroxylation of the C11 position of trans-24,25-dihydroxycholest-4-en-3-one to produce rosmolic acid; UGT74-345-2, UGT75-281-2, UGT720-269-1 and UGT720-269-4 are responsible for primary glycosylation at the C3 position, among which UGT720-269-1 is also the only enzyme responsible for primary glycosylation at the C24 position. UGT720-269-1, UGT94-289-1, UGT94-289-2 and UGT94-289-3 are responsible for the branched glycosylation of the C3 and C24 glucose chains.

3.3 Biosynthesis of cucurbitadienol

Li Shou-lian et al. [78] used a triterpenoid compound obtained in the laboratory to heterologously express and ferment the cloned SgCDS in the yeast chassis strain WD-2091 (FPS, SQS, SQE and MVA pathways were overexpressed and regulated), the cloned SgCDS was heterologously expressed and fermented, and the yield of cucurbitadienol was 27.44 mg/L. The CDS gene was further transferred from the high-copy plasmid pRS425 to the low-copy plasmid pRS313 to regulate the expression of the CDS gene, and the 313-SL-CB Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell factory was obtained, with a 202.07% increase in the production of cucurbitadienol. The high-density fermentation yield reached 1,724.10 mg/L, which is currently the highest yield of microbial synthesis of cucurbitadienol. This research has laid the foundation for the creation of an efficient cell factory for the production of cucurbit-type tetracyclic triterpenoids.

The construction of a microbial cell factory for M5 can involve transferring the original biosynthesis pathway or re-engineering and constructing the entire metabolic pathway. Although it has been proven that cucurbitadienol is not the skeleton for the synthesis of loganin, the engineered bacterium 313-SL-CB, which produces high levels of cucurbitadienol, can be used as a chassis cell. the oxidase gene can be recombined to convert cucurbitadienol to 24,25-epoxycucurbitadienol, and then catalyzed by EPH, CYP450 and glycosyltransferase to produce M5 (Figure 3).

4 Discussion and outlook

With the improvement of people's health awareness, consumers' pursuit of food is no longer limited to satisfying their taste buds, but also increasingly pay attention to its health and functionality, which has led to an “explosive” increase in the demand for natural non-sugar sweeteners [30]. In particular, M5, one of the world's strongest natural sweeteners, not only meets the public's demand as a natural non-sugar sweetener, but also serves as a sucrose substitute for diabetics and obese people due to its medicinal properties [79]. The demand for M5 is gradually increasing worldwide [80], and plant extraction methods can no longer meet market demand. Synthetic biology has unique advantages in the efficient and sustainable extraction of natural plant products, and has been applied to the synthesis of various natural products [81-83]. Therefore, the large-scale production of M5 using synthetic biology is an inevitable trend. At present, the biosynthetic pathway of M5 has been completely elucidated, and the key enzymes have been cloned and functionally verified, but research on microbial production is still lacking.

Based on the principles of synthetic biology, we propose two strategies for constructing a M5 cell factory: First, as mentioned above (Figure 3), the transformation to M5 can be achieved on the basis of the high-yielding cucurbitadienol-producing engineered bacterium 313-SL-CB, which is the most convenient way; second, the five enzyme genes involved in the conversion of 2,3;22,23-dioxo-squalene to M5 (Fig. 2) can be recombined into yeast cells to achieve de novo synthesis. There are still many difficulties in realizing the microbial production of M5 active molecules using these two strategies: First, the enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of squalene to 24,25-epoxysqualene in the first strategy has not been discovered, and the second strategy, the yeast's endogenous ERG1, cannot provide sufficient 2,3;22,23-bisepoxysqualene for SgCDS. Secondly, the M5 biosynthesis pathway involves many enzymes and intermediates, metabolic process is complex, and it is difficult to achieve efficient and coordinated expression of exogenous genes integrated into a single microbial cell, which also causes greater metabolic pressure on the host. Finally, SgCDS, UGT720-269-1 and UGT94-289-3 are all non-specific enzymes that can act on a variety of substrates to form different products, and the order and direction of catalysis in the chassis cell are difficult to control.

To address the problems, we propose the following strategies: identify and screen oxidases that catalyze the production of 24,25-epoxylupeol from lupeol and SQEs that efficiently catalyze the epoxidation reaction; more precisely regulate the downstream pathway of 2,3-epoxysqualene and and 2,3-epoxysqualene is more directed towards the synthesis of mogroside. In recent years, modular co-cultivation engineering has become a new strategy to reduce cell stress and increase the production of target products [84-85]. Therefore, the biosynthesis pathway of M5 can be reasonably divided into different modules, and each module can be integrated into a specific strain. The recruited strains can be integrated in one space, and then co-cultivate the recruited strains to achieve the de novo synthesis of M5. Structural biology is used to analyze the structure of enzyme proteins and understand the specific catalytic mechanism, and the substrate specificity of the farnesyltransferase and glycosyltransferase is enhanced through appropriate enzyme modification. Key compound real-time monitoring and metabolic dynamic regulation technology are developed to achieve directed catalysis of enzymes. With the development of synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, the low-cost, large-scale production of M5 will surely be realized.

Reference:

[1] Suez J, Korem T, Zeevi D, et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature, 2014, 514(7521): 181–186.

[2] Kokotou MG, Asimakopoulos AG, Thomaidis NS. Artificial sweeteners as emerging pollutants in the environment: analytical methodologies and environmental impact. Anal Methods, 2012, 4(10): 3057–3070.

[3] Gupta P, Gupta N, Pawar AP, et al. Role of sugar and sugar substitutes in dental caries: a review. ISRN Dent, 2013, 2013: 519421.

[4] Bray GA, Popkin BM. Dietary sugar and body weight: have we reached a crisis in the epidemic of obesity and diabetes?: health be damned! Pour on the sugar. Diabetes Care, 2014, 37(4): 950–956.

[5] Yang QH, Zhang ZF, Gregg EW, et al. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern Med, 2014, 174(4): 516–524.

[6] Świader K, Wegner K, Piotrowska A, et al. Plants as a source of natural high-intensity sweeteners: a review. J Appl Bot Food Qual, 2019, 92: 160–171.

[7] Kroger M, Meister K, Kava R. Low-calorie sweeteners and other sugar substitutes: a review of the safety issues. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf, 2006, 5(2): 35–47.

[8] Jin ML, Muguruma M, Moto M, et al. Thirteen-week repeated dose toxicity of Siraitia grosvenori extract in Wistar Hannover (GALAS) rats. Food Chem Toxicol, 2007, 45(7): 1231–1237.

[9] Kinghorn AD, Kaneda N, Baek NI, et al. Noncariogenic intense natural sweeteners. Med Res Rev, 1998, 18(5): 347–360.

[10] Adeogun O, Adekunle A, Ashafa A. Chemical composition, lethality and antifungal activities of the extracts of leaf of Thaumatococcus danielliiagainst foodborne fungi. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci, 2016, 5(4): 356–368.

[11] Goyal SK, Samsher, Goyal RK. Stevia (Stevia rebaudiana) a bio-sweetener: a review. Int J Food Sci Nutr, 2010, 61(1): 1–10.

[12] Singh DP, Kumari M, Prakash HG, et al. Phytochemical and pharmacological importance of stevia: a calorie-free natural sweetener. Sugar Tech, 2019, 21(2): 227–234.

[13] Jin JS, Lee JH. Phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of Siraitia grosvenorii, luo han kuo. Orient Pharm Exp Med, 2012, 12(4): 233–239.

[14] Zhang XB, Song YF, Ding YP, et al. Effects of mogrosides on high-fat-diet-induced obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Molecules, 2018, 23(8): 1894.

[15] Mizutani K, Kuramoto T, Tamura Y, et al. Sweetness of glycyrrhetic acid 3-O-β-D-monoglucuronide and the related glycosides. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 1994, 58(3): 554–555.

[16] Isbrucker RA, Burdock GA. Risk and safety assessment on the consumption of Licorice root (Glycyrrhiza sp.), its extract and powder as a food ingredient, with emphasis on the pharmacology and toxicology of glycyrrhizin. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol, 2006, 46(3): 167–192.

[17] DuBois GE, Prakash I.Non-caloric sweeteners, sweetness modulators, and sweetener enhancers. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol, 2012, 3: 353–380.

[18] Williamson EM, Liu XM, Izzo AA. Trends in use, pharmacology, and clinical applications of emerging herbal nutraceuticals. Br J Pharmacol, 2020, 177(6): 1227–1240.

[19] Matsumoto K, Kasai R, Ohtani K, et al. Minor cucurbitane-glycosides from fruits of Siraitia grosvenori (Cucurbitaceae). Chem Pharm Bull, 1990, 38(7): 2030–2032.

[20] Liu T, Wang XH, Li C, et al. Study on the antitussive, expectorant and antispasmodic effects of saponin V from Momordica grosvenori. Chin Pharm J, 2007, 42(20): 1534–1536, 1590 .

[21] Liu C, Dai LH, Dou DQ, et al. A natural food sweetener with anti-pancreatic cancer properties. Oncogenesis, 2016, 5(4): e217 .

[22] Takasaki M, Konoshima T, Murata Y, et al. Anticarcinogenic activity of natural sweeteners, cucurbitane glycosides, from Momordica grosvenori. Cancer Lett, 2003, 198(1): 37–42.

[23] Chen WJ, Wang J, Qi XY, et al. The antioxidant activities of natural sweeteners, mogrosides, from fruits of Siraitia grosvenori. Int J Food Sci Nutr, 2007, 58(7): 548–556.

[24] Zhou Y, Zheng Y, Ebersole J, et al. Insulin secretion stimulating effects of mogroside V and fruit extract of Luo Han Kuo (Siraitia grosvenori Swingle) fruit extract. Acta Pharm Sin, 2009, 44(11): 1252–1257.

[25] Tu DQ, Ma XJ, Zhao H, et al. Cloning and expression of SgCYP450-4 from Siraitia grosvenorii. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2016, 6(6): 614–622.

[26] Makapugay HC, Nanayakkara NPD, Soejarto DD, et al. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of the major sweet principle to Lo Han Kuo fruits. J Agric Food Chem, 1985, 33(3): 348–350.

[27] Rao SR, Ravishankar GA. Plant cell cultures: Chemical factories of secondary metabolites. Biotechnol Adv, 2002, 20(2): 101–153.

[28] Dudareva N, DellaPenna D. Plant metabolic engineering: future prospects and challenges. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2013, 24(2): 226–228.

[29] Smanski MJ, Zhou H, Claesen J, et al. Synthetic biology to access and expand nature’s chemical diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2016, 14(3): 135–149.

[30] Philippe RN, De Mey M, Anderson J, et al. Biotechnological production of natural zero-calorie sweeteners. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2014, 26: 155–161.

[31] Cameron DE, Bashor CJ, Collins JJ. A brief history of synthetic biology. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2014, 12(5): 381–390.

[32] Itkin M, Davidovich-Rikanati R, Cohen S, et al. The biosynthetic pathway of the nonsugar, high-intensity sweetener mogroside V from Siraitia grosvenorii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2016, 113(47): E7619–E7628.

[33] Li DP, Zhang HR. Studies and uses of Chinese medicine Luohanguo-a special local product of Guangxi. Guihaia, 2000, 20(3): 270–276.

[34] Lee CH. Intense sweetener from Lo Han Kuo (Momordica grosvenori). Experientia, 1975, 31(5): 533–534.

[35] Kasai R, Nie RL, Nashi K, et al. Sweet cucurbitane glycosides from fruits of Siraitia siamensis (chi-zi luo-han-guo), a Chinese folk medicine. Agric Biol Chem, 1989, 53(12): 3347–3349.

[36] Ukiya M, Akihisa T, Tokuda H, et al. Inhibitory effects of cucurbitane glycosides and other triterpenoids from the fruit of Momordica grosvenori on Epstein-Barr virus early antigen induced by tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. J Agric Food Chem, 2002, 50(23): 6710–6715.

[37] Wang L, Li LC, Fu YX, et al. Separation, synthesis, and cytotoxicity of a series of mogrol derivatives. J Asian Nat Prod Res, 2019: 1–15.

[38] Murata Y, Yoshikawa S, Suzuki YA, et al. Sweetness characteristics of the triterpene glycosides in Siraitia grosvenori. J Jpn Soc Food Sci Technol, 2006, 53(10): 527–533.

[39] Takemoto T, Arihara S, Nakajima T, et al. Studies on the constituents of fructus momordicae. I. On the sweet principle. Yakugaku Zasshi, 1983, 103(11): 1151–1154.

[40] Takemoto T, Arihara S, Nakajima T, et al. Studies on the constituents of fructus momordicae. II. Structure of sapogenin. Yakugaku Zasshi, 1983, 103(11): 1155–1166.

[41] Takemoto T, Arihara S, Nakajima T, et al. Studies on the constituents of fructus momordicae. III. Structure of mogrosides. Yakugaku Zasshi, 1983, 103(11): 1167–1173.

[42] Li DP, Ikeda T, Huang YL, et al. Seasonal variation of mogrosides in Lo Han Kuo (Siraitia grosvenori) fruits. J Nat Med, 2007, 61(3): 307–312.

[43] Itkin M, Heinig U, Tzfadia O, et al. Biosynthesis of antinutritional alkaloids in solanaceous crops is mediated by clustered genes. Science, 2013, 341(6142): 175–179.

[44] Harrison DM. The biosynthesis of triterpenoids, steroids, and carotenoids. Nat Prod Rep, 1990, 7(6):459–484.

[45] Lange BM, Ahkami A. Metabolic engineering of plant monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes and diterpenes-current status and future opportunities. Plant Biotechnol J, 2013, 11(2): 169–196.

[46] Bouvier F, Rahier A, Camara B. Biogenesis, molecular regulation and function of plant isoprenoids. Prog Lipid Res, 2005, 44(6): 357–429.

[47] Liao P, Hemmerlin A, Bach TJ, et al. The potential of the mevalonate pathway for enhanced isoprenoid production. Biotechnol Adv, 2016, 34(5): 697–713.

[48] Laule O, Fürholz A, Chang HS, et al. Crosstalk between cytosolic and plastidial pathways of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2003, 100(11): 6866–6871.

[49] Shibuya M, Adachi S, Ebizuka Y. Cucurbitadienol synthase, the first committed enzyme for cucurbitacin biosynthesis, is a distinct enzyme from cycloartenol synthase for phytosterol biosynthesis. Tetrahedron, 2004, 60(33): 6995–7003.

[50] Zhang JS, Dai LH, Yang JG, et al. Oxidation of cucurbitadienol catalyzed by CYP87D18 in the biosynthesis of mogrosides from Siraitia grosvenorii. Plant Cell Physiol, 2016, 57(5): 1000–1007.

[51] Lee JH, Weickmann JL, Koduri RK, et al. Expression of synthetic thaumatin genes in yeast. Biochemistry, 1988, 27(14): 5101–5107.

[52] Daniell S, Mellits KH, Faus I, et al. Refolding the sweet-tasting protein thaumatin II from insoluble inclusion bodies synthesised in Escherichia coli. Food Chem, 2000, 71(1): 105–110.

[53] Masuda T, Kitabatake N. Developments in biotechnological production of sweet proteins. J Biosci Bioeng, 2006, 102(5): 375–389.

[54] Ceunen S, Geuns JMC. Steviol glycosides: chemical diversity, metabolism, and function. J Nat Prod, 2013, 76(6): 1201–1228.

[55] Wang JF, Li SY, Xiong ZQ, et al. Pathway mining-based integration of critical enzyme parts for de novo biosynthesis of steviolglycosides sweetener in Escherichia coli. Cell Res, 2016, 26(2): 258–261.

[56] Olsson K, Carlsen S, Semmler A, et al. Microbial production of next-generation stevia sweeteners. Microb Cell Fact, 2016, 15: 207.

[57] Xu GJ, Cai W, Gao W, et al. A novel glucuronosyltransferase has an unprecedented ability to catalyse continuous two-step glucuronosylation of glycyrrhetinic acid to yield glycyrrhizin. New Phytol, 2016, 212(1): 123–135.

[58] Li C, Zhao YJ, Feng XD, et al. Application of glycosyl transferase in glycyrrhizic acid synthesis: CN, 110106222. 2019-08-09 .

[59] Liu JD, Zhang WP, Du GC, et al. Overproduction of geraniol by enhanced precursor supply in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biotechnol, 2013, 168(4): 446–451.

[60] Augustin JM, Kuzina V, Andersen SB, et al. Molecular activities, biosynthesis and evolution of triterpenoid saponins. Phytochemistry, 2011, 72(6): 435–457.

[61] Guo HH, Li RF, Liu SB, et al. Molecular characterization, expression, and regulation of Gynostemma pentaphyllum squalene epoxidase gene

1. Plant Physiol Biochem, 2016, 109: 230–239.

[62] Rasbery JM, Shan H, LeClair RJ, et al. Arabidopsis thaliana squalene epoxidase 1 is essential for root and seed development. J Biol Chem, 2007, 282(23): 17002–17013.

[63] Yu Y, Chang PC, Yu H, et al. Productive amyrin synthases for efficient α-amyrin synthesis in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Synth Biol, 2018, 7(10): 2391–2402.

[64] Wang ZH, Yeats T, Han H, et al. Cloning and characterization of oxidosqualene cyclases from Kalanchoe daigremontiana: enzymes catalyzing up to 10 rearrangement steps yielding friedelin and other triterpenoids. J Biol Chem, 2010, 285(39): 29703–29712.

[65] Yao Z, Zhou PP, Su BM, et al. Enhanced isoprene production by reconstruction of metabolic balance between strengthened precursor supply and improved isoprene synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Synth Biol, 2018, 7(9): 2308–2316.

[66] Paramasivan K, Mutturi S. Regeneration of NADPH coupled with HMG-CoA reductase activity increases squalene synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Agric Food Chem, 2017, 65(37): 8162–8170.

[67] Ro DK, Paradise EM, Ouellet M, et al. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature, 2006, 440(7086): 940–943.

[68] Nelson JA, Steckbeck SR, Spencer TA. Biosynthesis of 24, 25-epoxycholesterol from squalene 2,3;22,23-dioxide. J Biol Chem, 1981, 256(3): 1067–1068.

[69] Boutaud O, Dolis DH, Schuber F. Preferential cyclization of 2,3(S):22(S),23-dioxidosqualene by mammalian 2,3-oxidosqualene-lanosterol cyclase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1992, 188(2): 898–904.

[70] Godio RP, Fouces R, Martín JF. A squalene epoxidase is involved in biosynthesis of both the antitumor compound clavaric acid and sterols in the basidiomycete H. sublateritium. Chem Biol, 2007, 14(12): 1334–1346.

[71] Suzuki H, Achnine L, Xu R, et al. A genomics approach to the early stages of triterpene saponin biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula. Plant J, 2002, 32(6): 1033–1048.

[72] Zhao H, Guo J, Tang Q, et al. Cloning and expression analysis of squalene epoxidase genes from Siraitia grosvenorii. China J Chin Mater Med, 2018, 43(16): 3255–3262

[73] Wu TK, Chang CH, Liu YT, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae oxidosqualene-lanosterol cyclase: a chemistry-biology interdisciplinary study of the protein’s structure-function-reaction mechanism relationships. Chem Rec, 2008, 8(5): 302–325.

[74] Dai LH, Liu C, Zhu YM, et al. Functional characterization of cucurbitadienol synthase and triterpene glycosyltransferase involved in biosynthesis of mogrosides from Siraitia grosvenorii. Plant Cell Physiol, 2015, 56(6): 1172–1182.

[75] Han JY, Kim HJ, Kwon YS, et al. The Cyt P450 enzyme CYP716A47 catalyzes the formation of protopanaxadiol from dammarenediol-II during ginsenoside biosynthesis in Panax ginseng. Plant Cell Physiol, 2011, 52(12): 2062–2073.

[76] Caputi L, Malnoy M, Goremykin V, et al. A genome-wide phylogenetic reconstruction of family

1 UDP-glycosyltransferases revealed the expansion of the family during the adaptation of plants to life on land. Plant J, 2012, 69(6): 1030–1042.

[77] Tang Q, Ma XJ, Mo CM, et al. An efficient approach to finding Siraitia grosvenorii triterpene biosynthetic genes by RNA-seq and digital gene expression analysis. BMC Genomics, 2011, 12: 343.

[78] Li SL, Wang D, Liu Y, et al. Study of heterologous efficient synthesis of cucurbitadienol. China J Chin Mater Med, 2017, 42(17): 3326–3331.

[79] Xia Y, Rivero-Huguet ME, Hughes BH, et al. Isolation of the sweet components from Siraitia grosvenorii. Food Chem, 2008, 107(3): 1022–1028.

[80] Wang L, Yang ZM, Lu FL, et al. Cucurbitane glycosides derived from mogroside IIE: structure-taste relationships, antioxidant activity, and acute toxicity. Molecules, 2014, 19(8): 12676–12689.

[81] Liu LQ, Liu H, Zhang W, et al. Engineering the biosynthesis of caffeic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae with heterologous enzyme combinations. Engineering, 2019, 5(2): 287–295.

[82] Srinivasan P, Smolke CD. Engineering a microbial biosynthesis platform for de novo production of tropane alkaloids. Nat Commun, 2019, 10: 3634.

[83] Chen HF, Zhu CY, Zhu MZ, et al. High production of valencene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through metabolic engineering. Microb Cell Fact, 2019, 18: 195.

[84] Wang RF, Zhao SJ, Wang ZT, et al. Recent advances in modular co-culture engineering for synthesis of natural products. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2020, 62: 65–71.

[85] Li ZH, Wang XN, Zhang HR. Balancing the non-linear rosmarinic acid biosynthetic pathway by modular co-culture engineering. Metab Eng, 2019, 54: 1–11.

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese