Research on Encapsulation of Lutein Powder

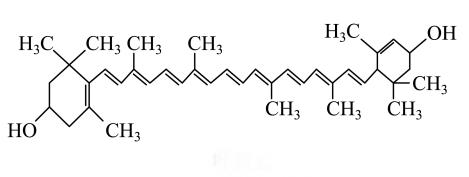

Carotenoids are divided into two categories based on their chemical structure: carotenoids and xanthophylls. Xanthophylls are a type of terpene compound in the xanthophyll group[1] that can be synthesized in the body to form vitamin A. They are also the main pigment in the macular region of the human eye's retina[2]. The human body cannot synthesize xanthophylls on its own, and most of the xanthophylls in the body come from dietary intake[3]. Lutein is found mainly in marigolds, egg products, green leafy vegetables and some fruits (Table 1). It is not only considered a natural food coloring agent, but also a natural antioxidant with a variety of biological activities [4].

Lutein can effectively resist ultraviolet radiation, prevent damage to retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells by blue light, and prevent the occurrence of various diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [5], cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and cancer [6]. According to statistics, most Americans get about 1 to 3 mg of lutein from their diet every day, while the recommended daily intake of lutein is 6 mg, indicating that their lutein intake is clearly insufficient. Lutein-containing functional foods or supplements should be provided to increase the average lutein intake level [7].

Lutein is a long-chain hydrophobic molecule with multiple conjugated double bonds in its molecular structure, so it is chemically unstable and sensitive to factors such as acidic conditions, oxygen, temperature and light. Therefore, it is easily affected by chemical, mechanical or physical factors during food processing, storage, transportation and application, leading to a loss of biological activity and product quality [10]. To address the shortcomings of lutein, such as its poor water solubility, poor physicochemical stability, and low bioavailability, researchers have conducted a large amount of research. At present, studies have been carried out in the fields of food and medicine on the use of delivery systems (such as liposomes, nanoparticles, emulsions, and microcapsules) to deliver lutein.

This review analyzes the reasons for the limited utilization of lutein, highlights the advantages and limitations of several lutein delivery systems, summarizes the current research status of these delivery systems to improve the solubility and bioavailability of lutein, and provides an outlook on the future development of lutein delivery systems.

1 Limitations of lutein application

Lutein is released into the gastrointestinal tract in large quantities by the human mouth through chewing and the action of enzymes, and is dispersed throughout the human digestive tract with the help of dietary fat, pancreatic juice and bile. It is dissolved during the mixed micelle period formed in the small intestine, and is then directly absorbed by epithelial cells and finally packaged into lipoproteins for transport to the bloodstream [11-12]. However, lutein has a low solubility and is difficult to absorb by the small intestinal epithelium, which results in a low absorption efficiency and bioavailability of lutein. Lutein is structurally very unstable and prone to isomerization, degradation and oxidation. Exposing foods containing lutein to extreme conditions such as deep frying and baking can reduce lutein content and activity [13-14]. Therefore, the bioavailability of lutein is mainly affected by food matrix [15], lipids [16], food processing methods [17], etc.

2 Encapsulation technology

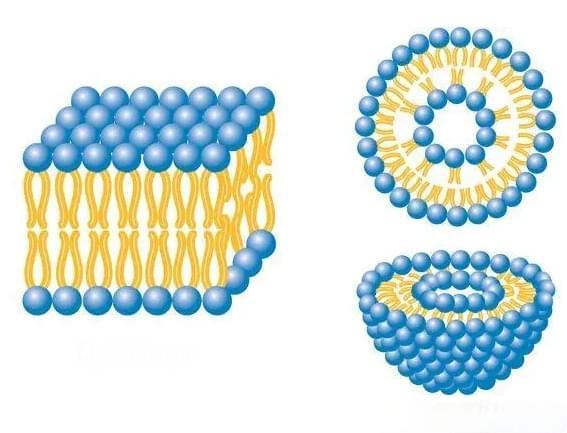

In the fields of food and pharmaceutical research, functional active substances (such as lutein) that are sensitive to external environments such as light, temperature and pH are often encapsulated to improve their water solubility, enhance stability, control delivery and release, and thereby improve their bioavailability. Commonly used lutein encapsulation systems include liposomes, nanoparticles, emulsions and microcapsules (Figure 1), and their characteristics are shown in Table 2.

2.1 Liposomes

Liposomes are spherical or nearly spherical vesicles with a bilayer structure, usually consisting of one or more phospholipid bilayers or lamellae. It has amphiphilic properties and can encapsulate both hydrophilic substances and lipophilic compounds. It can also encapsulate amphiphilic agents in the aqueous phase and on the phospholipids inside the membrane. Therefore, liposomes have good biocompatibility, sustained release properties and targeting properties, and can be used to encapsulate bioactive substances and inhibit their degradation under environmental conditions such as light [18]. Lutein liposomes were prepared using the ethanol injection method, in which lutein was embedded in the phospholipid bilayer. The phospholipid bilayer was used as a vesicle for targeted delivery, with an entrapment rate of 92%. However, there is a problem of organic solvent contamination [19]. The use of supercritical counter solvent to prepare liposomes composed of lutein and hydrogenated soy lecithin can solve the problem of organic solvent contamination, and the preparation process is simple, with an encapsulation rate of up to 90% [20]. Similarly, lutein liposomes can also be prepared using supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2).

Compared with other methods, SC-CO2 is environmentally friendly and has mild operating conditions. For liposomes prepared using SC-CO2, the encapsulation rate and position of lutein in the liposome depends on the pressure, because the reorganisation of phospholipid and lutein aggregates during the decompression process results in a higher encapsulation rate of lutein in the liposome (encapsulation rate of (97.0±0.8)%).[21] However, liposomes are thermodynamically unstable systems. In terms of physical and chemical stability, problems such as fusion, aggregation, phospholipid hydrolysis and oxidation during storage are prone to occur, and the storage conditions are too demanding.[22]

However, liposomes are thermodynamically unstable systems, and problems such as fusion, aggregation, phospholipid hydrolysis and oxidation during storage are prone to occur, which places high demands on storage conditions [22]. Nanoliposome technology can solve the above problems. It can improve the solubility and bioavailability of bioactive substances, as well as in vitro and in vivo stability. It is also one of the most widely studied encapsulation systems for protecting and controlling the release of lutein. For example, nano-lipids prepared with egg yolk lecithin and cholesterol as membrane materials can protect lutein, distribute it evenly within the nano-lipids, reduce the loss of lutein under various storage conditions such as light, heat, and pH, and also improve the antioxidant properties of lutein [23].

Lutein nano-lipids modified with the hydrophilic cationic polypeptide poly-L-lysine have an increased particle size and and the potential is increased. The digestion, absorption and utilization rate of lutein is also improved. This is because the polylysine binds to the lutein liposome through electrostatic adsorption, which improves the encapsulation rate of the liposome for lutein. In addition, the hydrophilicity and biological transdermal penetration of the polylysine are strong, which can improve the absorption and release properties of the lutein liposome in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby improving the bioavailability of lutein [24]. After the polypeptide is added to the lutein nanoliposome, in addition to improving the encapsulation and release properties of lutein, it can also improve the antioxidant activity and anticancer activity of the liposome, protecting lutein from oxidation in the external environment [25].

2.2 Nanoparticles

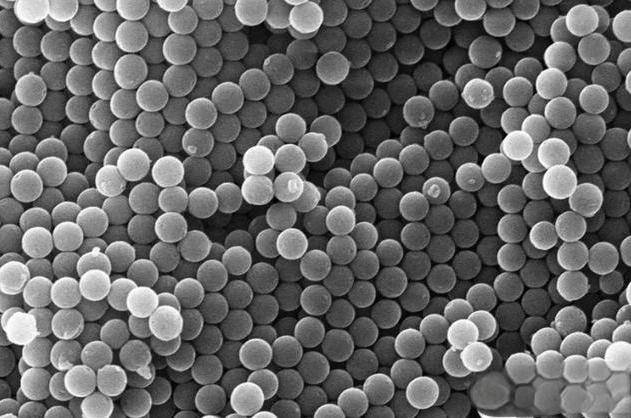

A nanoparticle delivery system refers to the use of nanoparticles to encapsulate and deliver bioactive ingredients in order to achieve the purpose of controlled release [26]. Nanoparticles are small in size, highly stable, and can carry a high drug loading rate. Encapsulating unstable nutrients in nanoparticle carriers can reduce their loss during food processing and storage. Therefore, constructing nanoparticles is a common and effective method for transporting substances in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industries [27]. Nanocarriers are generally polysaccharide nanoparticles, protein nanoparticles, and composite nanocarriers.

One of the most commonly used polysaccharides for preparing nanocarriers is chitosan. Chitosan-coated nanoparticles can promote the permeability of cell membranes, thereby enhancing intestinal epithelial absorption. They are also widely available and low-cost, so they can be used as an ideal wall material to encapsulate active substances [28]. Hong et al. [29] prepared chitosan/γ-polyglutamic acid nanoparticles that can improve the water solubility of lutein, which is 12 times that of unencapsulated lutein. Toragall et al. [30] used the ionogel method to prepare a chitosan-oleic acid-sodium alginate composite nanocarrier, which not only increased the solubility of lutein (1,000 times higher than free lutein), but also improved its thermal stability and bioavailability. Acute and subacute toxicity tests showed that there was no toxic effect even at higher concentrations (LD50>100 mg/kg mb).

Proteins commonly used as nanocarriers include proteins of animal origin or proteins of plant origin. Natural plant proteins come from a variety of sources, are generally cheaper and more readily available than animal proteins, and are sustainable and renewable. Natural plant proteins have become more popular than animal proteins in recent years, and are therefore an ideal source for the production of natural nanoparticles [31]. Zein, also known as corn gluten, is a natural plant macromolecule that is widely available, inexpensive, and rich in a variety of amino acids [32-33]. It has been widely studied and applied in fields such as food and medicine due to its good biocompatibility, biodegradability, self-assembly properties, and osteoinductivity [34-35]. Researchers have used a simple anti-solvent precipitation method to show that in a 75% ethanol solution by volume, zein can self-assemble with lutein to form spherical nanoparticles. Zein-loaded lutein nanoparticles can significantly reduce the photodegradation rate of the natural pigment lutein, with an encapsulation rate of about 80% [36]. However, nanoparticles made from a single protein are usually unstable. Lutein is protected in the stomach, but is easily degraded by proteases in the intestine, which damages the structure of the nanoparticles and reduces the micelle formation efficiency of lutein [37]. Therefore, protein-based nanoparticles usually need to be coated with a layer of other compounds to improve stability and encapsulation efficiency.

To improve colloidal stability, researchers have recently used polysaccharides such as gum, sodium alginate and carrageenan to stabilize zeaxanthin particles. However, the poor solubility of these polysaccharides in water and their high viscosity at room temperature may limit their application. Soybean polysaccharides are a natural anionic polysaccharide with excellent water solubility and low viscosity at room temperature. They can be used to stabilize zeaxanthin nanoparticles and improve their colloidal stability. Compared with pure zeaxanthin nanoparticles, the soy polysaccharide coating can act as a physical barrier to block light and oxygen, protecting the lutein from degradation. It can also hinder the hydrolysis of zeaxanthin by proteases in the stomach and intestines. Therefore, the water solubility, chemical stability, pH stability and salt stability of the zeaxanthin/soy polysaccharide composite nanoparticles are greatly improved [38]. In addition to polysaccharides stabilizing zeaxanthin particles, some small molecule surfactants can also improve colloidal stability. For example, when combined with tea saponin or locust bean gum, the encapsulation rate of the prepared nanoparticles can reach over 90%, and the water solubility is about 80 times that of lutein alone. Stability and bioavailability have also been greatly improved, and the addition of surfactants and lutein has changed the secondary structure of zein [39-40].

In addition to zein, some proteins from different sources have been used as carriers for lutein, such as rice protein and bovine serum albumin. Rice protein is recognized as a high-quality and nutritious natural plant protein due to its high biological potency, low allergenicity, high digestibility and high amino acid content. Xu Yu et al. [41] used natural rice protein as a raw material to develop a rice protease hydrolysate-carboxymethyl cellulose nanocarrier to encapsulate the fat-soluble bioactive molecule lutein, successfully constructing a food delivery system for lutein. This system can effectively protect lutein, improve its stability, and also effectively slow the release of lutein in the stomach, promote its release in the small intestine, inhibit the proliferation of breast cancer cells and promote cell absorption. Hou Huijing et al. [42] used bovine serum albumin to prepare bovine serum albumin-dextran-lutein nanoparticles, which can also improve the storage stability of lutein, with an encapsulation rate of 95%, and have better antioxidant activity in cells.

2.3 Emulsion systems

Traditional emulsions are made by mixing the oil and water phases, adding an emulsifier and homogenizing. They have low physical stability and are prone to demulsification in extreme environments (cooling, heating, high ionic strength and extreme pH). To solve these problems, a variety of emulsion systems with different structures and properties have been developed, such as microemulsions, multiple emulsions, nanoemulsions and Pickering emulsions.

2.3.1 Microemulsions

Microemulsions consist of at least three components: an immiscible non-polar phase, a polar phase and a surfactant. In some cases, additional components (e.g. co-surfactants) are required. These components form a stable thermodynamic system in the right proportions that is colorless, transparent (or translucent) and has low viscosity [43-44]. The preparation of microemulsions requires a higher surfactant concentration than conventional emulsions, but the preparation process is simpler. They also have the effect of improving the digestibility of food components, resisting oxidation, and inhibiting bacteria, so they are widely used to encapsulate hydrophobic substances and improve their bioavailability in the gastrointestinal tract [45]. Microemulsions prepared using a food-grade nonionic surfactant (Tween-80) have been shown to effectively encapsulate lutein and zeaxanthin in beverages and improve their bioavailability [46].

The loading capacity of the lutein microemulsion formed with 30.00% medium-chain triglycerides (MCT), 41.37% polyoxyethylene hydrogenated castor oil (cremophor RH40), and 28.63% polyethylene glycol-400 (PEG-400) was 1 mg/g. It can be basically dissolved within 10 minutes, with a dissolution percentage of about 67%. However, the loading amount is low, and it is easily degraded in an acidic environment, so further research is needed [47].

Lutein microemulsions were prepared using Tween-80 as the surfactant and anhydrous ethanol as the co-surfactant using the phase inversion emulsification method. This method can overcome the thermodynamic instability of ordinary emulsions, improve the water solubility of lutein, and can be used in actual food production [48]. However, the large amount of surfactant and co-surfactant used in the process of microemulsion formation increases the toxicity of the microemulsion. In addition, during the food processing, the microemulsion structure will be diluted by the aqueous phase and destroyed due to the addition of various ingredients, causing phase transition of the microemulsion. In addition to encapsulating lutein, microemulsion can also be used as an extractant to extract lutein from marigolds, gradually becoming a new method of lutein extraction.

2.3.2 Multiple emulsions

Multiple emulsions are a complex three-phase system in which the dispersed phase of the emulsion also contains droplets of another phase that are immiscible with it [49]. There are many types of multiple emulsions, including oil in water in oil (O/W/O) and water in oil in water (W/O/W) [50]. When traditional emulsions are embedded, leaks often occur, resulting in a low embedding rate. Compared with traditional emulsions, multi-emulsions have a high embedding rate and can simultaneously embed substances with different affinities. They are widely used in food, medicine, cosmetics and other fields [51]. For example, using electrostatic layer-by-layer assembly technology, lutein emulsions with different interfacial layers were formed using whey protein isolate, chitosan and linseed gum. The physical and chemical stability of the two-layer and three-layer emulsions was significantly better than that of the single-layer emulsion [52]. Multilayer emulsions formed from fish gelatin, whey protein isolate and dodecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide have also been shown to improve the stability of lutein [53].

2.3.3 Nanoemulsions

Nanoemulsions are thermodynamically unstable systems with an average particle size of 50–200 nm [54]. Nanoemulsions are usually classified as water in oil (W/O), oil in water (O/W) or bicontinuous (B.C) [55]. Compared with traditional emulsions, nanoemulsions have smaller particle sizes, are less prone to settling during storage, and can prevent flocculation in the system. Therefore, researchers widely use nanoemulsions to encapsulate active ingredients to improve their physical and chemical stability and bioavailability [56]. Lutein nanomilks constructed using high-pressure homogenization with sodium caseinate as an emulsifier showed significant free radical scavenging activity, and the nanomilks remained physically stable after being stored at 4 °C for 30 days, effectively reducing the chemical degradation rate of lutein [57-58]. Although proteins are considered to be good emulsifiers, they are generally sensitive to changes in pH, high temperatures, high ionic strength, etc., and have low solubility near their isoelectric point.

To solve this problem, Gumus et al. [59] found that emulsions with a casein-glucan Maillard complex as an emulsifier have good protection for lutein at pH 3–7 and at different temperatures. This is because the glucan provides strong steric hindrance, and the Maillard complex does not affect the digestion of lutein.

Caballero et al. [60] developed a lutein emulsion with a pea protein-dextran Maillard complex as an emulsifier. Compared with a casein-dextran Maillard complex, both can provide better physical stability under different ionic strengths and storage temperatures, but neither can inhibit lutein fading. Some scholars have found that adding resveratrol and grape seed oil to nanoemulsions prepared from a casein-glucan Maillard covalent complex can inhibit lutein degradation and lutein discoloration at different temperatures, effectively improving the chemical stability of lutein. This is because resveratrol has strong antioxidant properties, and in addition, grape seed oil contains endogenous antioxidants, further improving the chemical stability of lutein [61]. However, the application of nanoemulsions is still limited at present. One reason is that the thermodynamic properties of nanoemulsions are unstable, and heating is not conducive to their stability. In addition to thermodynamic instability, the industrial application of nanoemulsions is also limited by production costs, toxicity and other factors [62]. Therefore, in-depth research is still needed to improve the thermal stability of nanoemulsions.

2.3.4 Pickering emulsions

Pickering emulsions are emulsions stabilized by solid particles as emulsifiers rather than surfactants [63]. These solid particles have a well-defined particle size distribution and can reduce the interfacial energy between oil and water, which helps to produce a stable Pickering emulsion [64]. Compared with traditional emulsions, Pickering emulsions have the advantages of low toxicity, high anti-coagulation stability and high storage stability. At the same time, they can also encapsulate bioactive ingredients and protect, deliver and control the release of their ingredients. They have a wide range of applications in the food and pharmaceutical industries [65-67]. At present, the solid particles commonly used to stabilize Pickering emulsions are generally polysaccharides, proteins and composite particles. Li Songnan et al. [68] constructed Pickering emulsion gels with different interfacial activities and emulsion structures by adjusting the volume fraction of the oil phase. The Pickering emulsion gels were made of octenyl succinate quinoa starch (OSQS) and used to deliver lutein. After 31 days of storage, the retention rate of lutein reached 55.38%.

SuJiaqi et al. [69] used β-lactoglobulin-gum arabic as a particle stabilizer for lutein delivery. The Pickering emulsion prepared had high resistance to flocculation and coagulation, and was chemically stable. After 12 weeks of storage, 91.1% of the lutein was still retained. In addition to binding to polysaccharides, proteins can also form protein-based complex particles with epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) through non-covalent interactions. The complex particles stabilize the Pickering emulsion and can inhibit the degradation of lutein [70].

In recent years, although edible solid particles such as proteins and polysaccharides have been widely used due to their low toxicity, environmental friendliness and high stability, they have certain limitations. Methods such as hydrolysis, heating and compounding are required to improve their wettability, particle size and surface roughness. In addition, there have been few studies on the use of Pickering emulsions to improve the bioavailability of lutein when used for encapsulation. Therefore, research is still needed on the preparation of Pickering emulsions using novel solid particles with good amphiphilicity and edibility, and on the use of Pickering emulsions to improve the bioavailability of lutein. Table 3 summarizes the various types of emulsions used for lutein delivery and their properties.

2.4 Microcapsules

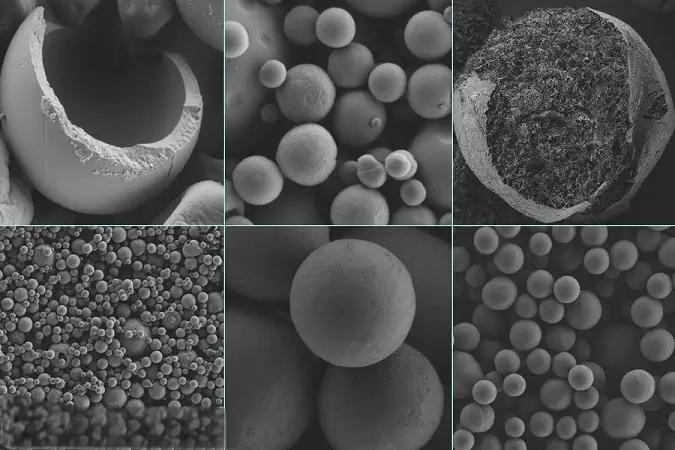

Microcapsules are tiny particles made of a film-forming material that enclose sensitive, volatile or reactive solids or liquids. They have a wide range of applications, such as protecting the stability and delaying the release of natural active ingredients. However, they still have disadvantages such as environmental pollution and long core material release times [71]. Many studies have shown that the microencapsulation of lutein can improve the water solubility and stability of lutein and control the release of lutein [72-73].

Among the microencapsulation methods, spray drying technology has the advantages of high productivity, low energy consumption, short development cycle, and good flexibility. It has become one of the most important microencapsulation methods in the food industry for decades [74]. In the spray drying microencapsulation process, the selection of the microcapsule wall material is crucial. Among the various types of microcapsule wall materials, polysaccharide polymers (such as oligosaccharides, maltodextrin, hyaluronic acid and starch) are the most commonly used due to their low cost, high solubility, low viscosity and antioxidant properties [75]. Zhang Lihua et al. [76] dispersed lutein evenly in a modified starch and sucrose matrix, and then coated with corn starch. The lutein microcapsules were prepared using spray drying technology. The prepared lutein microcapsules can directly dissolve lutein in water to form a uniform liquid, which improves the solubility and storage stability of lutein and increases the bioavailability of lutein. The relative bioavailability also reached 139.1%.

Ding Zhuang et al. [77] selected three different types of polysaccharides (trehalose, inulin and modified starch) and their combinations to prepare lutein microcapsules using a three-factor three-level experiment. The study showed that the maximum encapsulation rate of microcapsules with inulin and modified starch as composite embedding materials was (80.0 ± 0.6)%, and the stability was also significantly improved. In addition to polysaccharide polymers, the wall materials of microcapsules also include protein polymers (such as proteins and gelatin), which have good biodegradability and compatibility [78].

In recent years, the selection of suitable protein wall materials and the compounding and modification of proteins have become research hotspots. Qu Xiaoying et al. [72] used gum arabic and gelatin as the wall materials for microcapsules, prepared lutein microcapsules by coacervation, and optimized the preparation conditions to improve the stability of lutein to light, temperature, and relative humidity. Zhao Tong et al. [79] prepared different lutein microcapsules (lecithin-lutein microcapsules and casein-lutein microcapsules) and studied the effects of temperature, light and pH on the stability of lutein. The results showed that casein-lutein microcapsules had better stability and were more easily absorbed by intestinal Caco-2 cells than natural lutein.

3 Conclusion

In recent years, the physiological and functional activities of lutein have been widely studied. The intake of an appropriate amount of lutein not only contributes to eye health, but also prevents cardiovascular diseases and promotes brain development. Lutein is also a natural food coloring agent and antioxidant. However, the poor water solubility, chemical stability and low bioavailability of lutein have limited its application in foods. However, various encapsulation systems (such as liposomes, nanoparticles, emulsion systems and microcapsules) can improve the encapsulation, delivery and release of lutein, and increase its bioavailability in the human body.

However, there are also some shortcomings in the development of lutein encapsulation systems. For example, there is the issue of the color of lutein, which is a natural coloring agent, so the chemical degradation rate of products containing lutein needs to be considered. There are also issues with some encapsulation techniques, such as high costs, difficulties in industrial production, and the safety of nanoscale encapsulation systems. In addition, there is little research on the digestion, absorption and metabolism of lutein in various delivery systems, and the role of different delivery systems in the absorption and metabolism of lutein needs to be further understood. Therefore, future trends should focus on researching economically viable lutein delivery systems for large-scale industrial production, the safety of nano-scale encapsulation systems, the mechanism of digestion and absorption, and the development of more embedding systems assembled from natural food-grade polymers (such as proteins and polysaccharides).

References:

[1] Liu Yang, Chen Mingjun, Song Xiang, et al. Effect of lutein on the degree of inflammatory response in atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid artery [J]. Food Science, 2018, 39(9): 170-175.

[2]ABDEL-AAL E M, AKHTAR H, ZAHEER K, et al. Dietary sources of lutein and zeaxanthin carotenoids and their role in eye health[J]. Nutrients, 2013, 5(4): 1169-1185. DOI:10.3390/nu5041169.

[3] Hou Yanmei, Wu Tong, Xie Kui. Research progress on the biological activity of lutein [J]. China Food and Nutrition, 2020, 26(10): 5-8. DOI:10.19870/j.cnki. 11-3716/ ts.20200902.001.

[4]BECERRA M O, CONTRERAS L M, LO M H, et al. Lutein as a functional food ingredient: stability and bioavailability[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2020, 66: 103711. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2019.103771.

[5]GONG Xiaoming, DRAPER C S, ALLISON G S, et al. Effects of the macular carotenoid lutein in human retinal pigment epithelial cells[J]. Antioxidants, 2017, 6(4): 100. DOI:10.3390/antiox6040100.

[6] EGGERSDORFER M, WYSS A. Carotenoids in human nutrition and health[J]. Archive of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2018, 652: 18-26. DOI:10.1016/j.abb.2018.06.001.

[7] Ma Le, Lin Xiaoming. Effect of lutein intervention on visual function in people with long-term screen light exposure [J]. Journal of Nutrition, 2008(5): 438-442.

[8] Zhu Haixia, Zheng Jianxian. Structure, distribution, physical and chemical properties and physiological functions of lutein [J]. China Food Additives, 2005(5): 48-55.

[9] Wang Zixin, Lin Xiaoming. Determination and content of lutein, zeaxanthin and β-carotene in common vegetables in Beijing [J]. Journal of Nutrition, 2010, 32(3): 290-294.

[10]BHAT I, YATHISHA U G, KARUNASAGAR I, et al. Nutraceutical approach to enhance lutein bioavailability viananodelivery systems[J]. Nutrition Reviews, 2020, 78(9): 709-724. DOI:10.1093/nutrit/nuz096.

[11]JOHNSON E J. A biological role of lutein[J] . Food Reviews International, 2004, 20(1): 1-16. DOI:10.1081/fri-120028826.

[12] Lei Fei, Gao Yanxiang, Hou Zhanqun. Factors affecting the bioavailability of carotenoids during in vitro digestion [J]. Food Science, 2012, 33(21): 368-373.

[13]ZHANG Dongxue, WANG Lina, ZHANG Xin, et al. Polymeric micelles for pH-responsive lutein delivery[J] . Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, 2018, 45: 281-286. DOI:10.1016/ j.jddst.2018.03.023.

[14]MATinging, TIAN Chengrui, LUO Jiyang, et al. Influence of technical processing units on the alpha-carotene, beta-carotene and lutein contents of carrot (Daucus carrot L.) juice[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2015, 16: 104-113.

[15]MARGIER M, BUFFIERE C, GOUPY P, et al. Opposite effects of the spinach food matrix on lutein bioaccessibility and intestinal uptake lead to unchanged bioavailability compared to pure lutein[J]. Molecular Nutrition Food Research, 2018, 62(11): 1800185. DOI:10.1002/mnfr.201800185.

[16]CHUREEPORN C, SCHWARTZ S J, FAILLA M L. Assessment of lutein bioavailability from meals and a supplement using simulated digestion and Caco-2 human intestinal cells[J]. Journal of Nutrition, 2004, 134(9): 2280-2286.

[17] Xie Xiaoye, Li Dajing, Song Jiangfeng, et al. Stability of lutein during bread processing and storage [J]. Food Science, 2014, 35(20): 271-275. DOI:10.7506/spkx1002-6630- 201420053.

[18] Hou Lifen, Gu Kerren, Wu Yonghui. Research progress in the preparation methods of lipid systems with different formulations [J]. Journal of Henan University of Technology (Natural Science Edition), 2016, 37(5): 118-124. DOI: 10.16433/j.cnki.issn1673-2383.2016.05.021.

[19]TAN Chen, XIA Shunqi, XUE Jin, et al. Liposomes as vehicles for lutein: preparation, stability, liposomal membrane dynamics, and

structure[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2013, 61(34): 8175-8184. DOI:10.1021/jf402085f.

[20]XIA Fei, HU Daode, JIN Heyang, et al. Preparation of lutein proliposome s by supercritical anti -solvent technique [J] . Food Hydrocolloids, 2012, 26(2): 456-463. DOI:10. 1016/ j.foodhyd.2010.11.014.

[21]ZHAO Lisha, TEMELLI F, CURTIS J M, et al. Encapsulation of lutein in liposomes using supercritical carbon dioxide[J] . Food Research International, 2017, 100(1): 168-179. DOI:10. 1016/ j.foodres.2017.06.055.

[22]XIAO Yanyu, SONG Yunmei, CHEN Zhipeng, et al. Preparation of silymarin proliposome: a new way to increase oral bioavailability of silymarin in beagle dogs[J]. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 2006, 319(1/2): 162-168.

[23] Jiao Yan, Li Dajing, Liu Chunquan, et al. Optimization of the preparation process of lutein nanoliposomes and their oxidative stability [J]. Food Science, 2017, 38(18): 259-265. DOI:10.7506/ spkx1002-6630-201718040.

[24] Jiao Yan, Gao Jianing, Chang Ying, et al. Polylysine modification of lutein nanoliposomes and their in vitro release properties [J]. China Oil and Fat, 2021, 46(3): 62-67. DOI:10.19902/ j.cnki.zgyz.1003-7969.2021.03.013.

[25]JIAO Yan, LI Dajing, LIU Chunquan, et al. Polypeptide-decorated nanoliposomes as novel delivery systems for lutein[J]. RSC Advances, 2018, 8(55): 31372-31381. DOI:10.1039/c8ra05838e.

[26]JOYE I J, MCCLEMENTS D J. Biopolymer-based nanoparticles and microparticles: fabrication, characterization, and application[J]. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science, 2014, 19(5): 417-427. DOI:10.1016/j.cocis.2014.07.002.

[27]RASHIDI L, KHOSRAVI - DARANI K . The applications of nanotechnology in food industry[J] . Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2011, 51(8): 723- 730. DOI:10.1080/10408391003785417.

[28] Kuang H, Hu C, Wen X, et al. Properties of nanometer ZnO/chitosan composite membrane and its application in the preservation of fresh-frozen pork [J]. Food and Fermentation Industry, 2017, 43(4): 251-256. DOI:10.13995/j.cnki.11-1802/ts.201704040.

[29]HONG D Y, LEE J S, LEE H G. Chitosan/poly-gamma-glutamic acid nanoparticles improve the solubility of lutein[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2016, 85: 9-15. DOI:10.1016/ j.ijbiomac.2015.12.044.

[30]TORAGALL V, JAYAPALA N, VALLIKANNAN B. Chitosan-oleic acid-sodium alginate a hybrid nanocarrier as an efficient delivery system for enhancement of luteinstability and bioavailability[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 150: 578-594.

[31] Tao Linlin, Huo Meirong, Xu Wei. Research progress of protein-based nanocarrier materials [J]. Journal of China Pharmaceutical University, 2020, 51(2): 121-129. DOI: 10. 11665/ j.issn.1000-5048.20200201.

[32] Yu Xianglong, Wu Yali, Du Shouying, et al. Research progress of zein as a nanocarrier [J]. Natural Product Research and Development, 2020, 32(8): 1438-1477. DOI:10.16333/j.1001-6880.2020.8.021.

[33] Wang Lijuan. Preparation and application research of zein colloidal particles [D]. Guangzhou: South China University of Technology, 2014: 1-5.

[34]KASAAI M R. Zein and zein-based nano-materials for food and nutrition applications: a review[J] . Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2018, 79: 184-197. DOI:10.1016/j.tifs.2018.07.015.

[35]SINGH S, GAIKWAD K K, LEE M, et al. Microwave-assisted micro-encapsulation of phase change material using zein for smart food packaging applications[J]. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2017, 131(3): 2187-2195.

[36]DE BOER F Y, IMHOF A, VELIKOV K P. Photo-stability of lutein in surfactant-free lutein-zein composite colloidal particles[J]. Food Chemistry: X, 2020, 5: 100071. DOI:10.1016/j.fochx.2019.100071.

[37]CHENG C J, FERRUZZI M, JONES O G. Fate of lutein-containing zein nanoparticles following simulated gastric and intestinal digestion[J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2019, 87: 229-236. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodhyd.2018.08.013.

[38]LI Hao, YUAN Yongkai, ZHU Junxiang, et al. Zein/soluble soybean polysaccharide composite nanoparticles for encapsulation and oral delivery of lutein[J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2020, 103: 105715. DOI:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105715.

[39]MA Mengjie, YUAN Yongkai, YANG Shuang, et al. Fabrication and characterization of zein/tea saponin composite nanoparticles as delivery vehicles of lutein[J]. Food Science and Technology, 2020, 125: 109270. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109270.

[40]YUAN Yongkai, LI Hao, LIU Chengzhen, et al. Fabrication and characterization of lutein-loaded nanoparticles based on zein and sophorolipid: enhancement of water solubility, stability, and bioaccessibility[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2019, 67(43): 11977-11985.

[41]XU Yu, MA Xiaoyu, GONG Wei, et al. Nanoparticles based on carboxymethylcellulose-modified rice protein for efficient delivery of lutein[J]. Food & Function, 2020, 11(3): 2380-2394. DOI:10.1039/c9fo02439e.

[42] Hou Huijing, Zhang Xiaoyan, Chen Jianbo, et al. Preparation of BSA-dextran-lutein nanoparticles and their antioxidant activity [J]. Food Research and Development, 2020, 41(20): 137-145. DOI:10.12161/j.issn.1005-6521.2020.20.023.

[43]ASGARI S, SABERI AH, MCCLEMENTS D J, et al. Microemulsions as nanoreactors for synthesis of biopolymer nanoparticles[J]. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2019, 86: 118-130. DOI:10.1016/ j.tifs.2019.02.008.

[44]HUIE C W. Recent applications of microemulsion electrokinetic chromatography[J]. Electrophoresis, 2006, 27(1): 60-75. DOI:10.1002/ elps.200500518.

[45] Yang Guanjie, Liang Peng. Research progress of microemulsions in the field of food nutrition and safety [J]. Food Research and Development, 2020, 41(8): 210- 217. DOI:10. 12161 / j.issn.1005-6521.2020.08.035.

[46]AMAR I, ASERIN A, GARTI N. Microstructure transitions derived from solubilization of lutein and lutein esters in food microemulsions[J]. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2004, 33(3/4): 143-150. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2003.08.009.

[47] Hu Chunli, Yang Beibei, Zhang Linjie, et al. Preparation and quality control of lutein self-microemulsion [J]. Today's Pharmacy, 2019, 29(9): 378-383. DOI: 10.12048/j.issn. 1674- 229X.2019.09.004.

[48] Cheng Lingyun, Huang Guoqing, Xiao Junxia, et al. Preparation process research of water-dispersible lutein microemulsion [J]. Chinese Condiments, 2014, 39(12): 85-89; 93. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-9973.2014.12.022.

[49]GART I N. Double emulsions- scope, limitations and new achievements[J]. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 1997, 123/124: 233-246. DOI:10.1016/S0927- 7757(96)03809-5.

[50]GUZEY D, MCCLEMENTS D J. Formation, stability and properties of multilayer emulsions for application in the food industry[J] . Advances in Colloid and Interface Science, 2006, 128/129/130: 227-248. DOI:10.1016/j.cis.2006.11.021.

[51] Xu Wenhua, Zhang Jia, Wang Zihan, et al. Progress in the preparation and application of double emulsions [J]. Food and Machinery, 2020, 36(9): 1–11. DOI:10.13652/j.issn.1003-5788.2020.09.001.

[52]XU Duoxia, AIHEMAITI Z, CAO Yanping, et al. Physicochemical stability, microrheological properties and microstructure of lutein emulsions stabilized by multilayer membranes consisting of whey protein isolate, flaxseed gum and chitosan[J]. Food Chemistry, 2016, 202: 156-164. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.052.

[53] BEICHT J, ZEEB B, GIBIS M, et al. Influence of layer thickness and composition of cross-linked multilayered oil-in-water emulsions on the release behavior of lutein[J]. Food Function, 2013, 4(10): 1457-1467. DOI:10.1039/c3fo60220f.[54] MELESON K, GRAVES S, MASON T G. Formation of concentrated nanoemulsions by extreme shear[J]. Soft Materials, 2004, 2(2/3): 109-123.

[55] Deng Lingli, Yu Liyi, Maerhaba Tashipalati, et al. Research progress of nanoemulsions and microemulsions [J]. Chinese Journal of Food Science, 2013, 13(8): 173-180. DOI:10.16429/j.1009-7848.2013.08.023.

[56]CHOI S J, MCCLEMENTS D J. Nanoemulsions as delivery systems for lipophilicnutraceuticals: strategies for improving their formulation, stability, functionality and bioavailability[J] . Food Science and Biotechnology, 2020, 29(2): 149-168.

[57] Li Jinan, Hu Hao, Wu Xuejiao, et al. Effect of environmental factors on the stability and antioxidant activity of lutein nanodispersions [J]. Food Science, 2019, 40(19): 32-39. DOI:10.7506/ spkx1002-6630-20181028-322.

[58]LI Jinan, GUO Rui, HU Hao, et al. Preparation optimisation and storage stability of nanoemulsion-based lutein delivery systems[J]. Journal of Microencapsulation, 2018, 35(6): 570-583. DOI:10.1080/ 02652048.2018.1559245.

[59]GUMUS C E, DAVIDOV-PARDO G, MCCLEMENTS D J. Lutein- enriched emulsion-based delivery systems: Impact of Maillard conjugation on physicochemical stability and gastrointestinal fate[J] . Food Hydrocolloids, 2016, 60: 38-49 .

[60]CABALLERO S, DAVIDOV-PARDO G. Comparison of legume and dairy proteins for the impact of Maillard conjugation on nanoemulsion formation, stability, and lutein color retention[J]. Food Chemistry, 2021, 338: 128083.

[61]STEINER B M, SHUKLA V, MCCLEMENTS D J, et al. Encapsulation of lutein in nanoemulsions stabilized by resveratroland Maillard conjugates[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2019, 84(9): 2421-2431.

[62]KUMAR D H L, SARKAR P. Encapsulation of bioactive compounds using nanoemulsions[J]. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 2017, 16(1): 59-70. DOI:10.1007/s10311-017-0663-x.

[63] Liu Qian, Chang Xia, Shan Yang, et al. Research progress of functional Pickering emulsions [J]. Chinese Journal of Food Science, 2020, 20(11): 279-293. DOI:10.16429/j.1009-7848.2020.11.033.

[64]SHI Aimin, FENG Xinyue, WANG Qiang, et al. Pickering and high internal phase Pickering emulsions stabilized by protein-based particles: a review of synthesis, application and prospective[J] . Food Hydrocolloids , 2020, 109: 106117.

[65]CHEN Lijuan, AO Fen, GE Xuemei, et al. Food-grade pickering emulsions: preparation, stabilization and applications[J]. Molecules, 2020, 25(14): 3202. DOI:10.3390/molecules25143202.

[66]ANUJN, GAMOTT D, OOI C W, et al. Biomolecule-based pickering food emulsions: intrinsic components of food matrix, recent trends and prospects[J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2021, 112: 106303. DOI:10.1016/ j.foodhyd.2020.106303.

[67]JIANG Hang, SHENG Yifeng, NGAI T. Pickering emulsions: versatility of colloidal particles and recent applications[J]. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science, 2020, 49: 1-15. DOI:10.1016/ j.cocis.2020.04.010.

[68]LI Songnan, ZHANG Bin, LI Chao, et al. Pickering emulsion gel stabilized by octenylsuccinate quinoa starch granule as lutein carrier: role of the gel network[J]. Food Chemistry, 2020, 305: 125476. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125476.

[69]SU Jiaqi, GUO Qing, CHEN Yulu, et al. Characterization and formation mechanism of lutein pickering emulsion gels stabilized by β-lactoglobulin-gum arabic composite colloidal nanoparticles[J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2020, 98: 105276.

[70]SU Ji aqi, GUO Qing, CHEN Yulu, et al. Utilization of β-lactoglobulin-(-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) composite colloidal nanoparticles as stabilizers for lutein pickering emulsion[J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2020, 98: 105293.

[71] Geng Feng, Shao Meng, Wei Jian, et al. Research progress on the application of microencapsulation technology in the protection of natural active ingredients [J]. Food and Drugs, 2020, 22(3): 250-255. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-979X.2020.03.018.

[72]QU Xiaoying, ZENG Zhipeng, JIANG Jianguo. Preparation of lutein microencapsulation by complex coacervation method and its physicochemical properties and stability[J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2011, 25(6): 1596-1603.

[73]WANG Yufeng, YE Hong, ZHOU Chunhong, et al. Study on the spray- drying encapsulation of lutein in the porous starch and gelatin mixture[J]. European Food Research and Technology, 2012, 234(1): 157-163.

[74]SCHUCK P, JEANTET R, BHANDARI B, et al. Recent advances in spray drying relevant to the dairy industry: a comprehensive critical review[J]. Drying Technology, 2016, 34(15): 1773-1790. DOI:10. 1080/07373937.2016.1233114.

[75]DIMA A, DIMA C, IORDACHESCU G. Encapsulation of functional lipophilic food and drug biocomponents[J] . Food Engineering Reviews, 2015, 7(4): 417-438. DOI:10.1007/s12393-015-9115-1.

[76]ZHANG Lihua, XU Xinde, SHAO Bin, et al. Physicochemical properties and bioavailability of lutein microencapsulation (LM)[J]. Food Science and Technology Research, 2015, 21(4): 503-507. DOI:10.3136/fstr.21.503.

[77]DING Zhuang, TAO Tao, YIN Xiaohan, et al. Improved encapsulation efficiency and storage stability of spray dried microencapsulated lutein with carbohydrates combinations as encapsulating material[J]. Food Science and Technology, 2020, 124: 109139.

[78] Lou Wenyong, Zhong Shurui, Zhang Zhihua, et al. Research progress of protein-based microcapsule wall materials [J]. Journal of South China University of Technology (Natural Science Edition), 2019, 47(12): 116-125.

[79]ZHAO Tong, LIU Fuguo, DUAN Xiang, et al. Physicochemical properties of lutein-loaded microcapsules and their uptake via Caco-2 monolayers[J] . Molecules, 2018, 23(7): 1805.

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese