Is Cranberry Extract Good for Urinary Tract Infection(UTI)?

Cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon) are a species of the bilberry genus and are one of the three traditional North American fruits (the other two being grapes and blueberries). It grows in a unique environment and adapts to cool climates. It grows from Newfoundland in the north to Minnesota in the west and North Carolina in the south. The medicinal value of cranberries was discovered by North American folk long ago, and there are records from 1800 of cranberries being used to treat scurvy in sailors. A recent medical survey showed that after the US liberalized its dietary supplement and herbal medicine market, cranberry preparations became the first choice of health care drugs for the prevention of urinary tract infections [1].

Fresh cranberries are extremely sour and astringent and must be sweetened or processed in other ways. There are many types of cranberry health foods, such as juice concentrates, freeze-dried powdered jelly, fruit sauces, fruit juice drinks, cocktail-style mixed drinks, tablets, powders, etc. Research on the health benefits of cranberries has focused on anti-infective, antioxidant and anti-tumor effects. As cranberries are a traditional food that has long been used as a health food by Native Americans, it is possible to directly observe and test their efficacy in human populations, unlike drugs or some uncommon foods that need to be tested on animals first.

1 Anti-infective effects

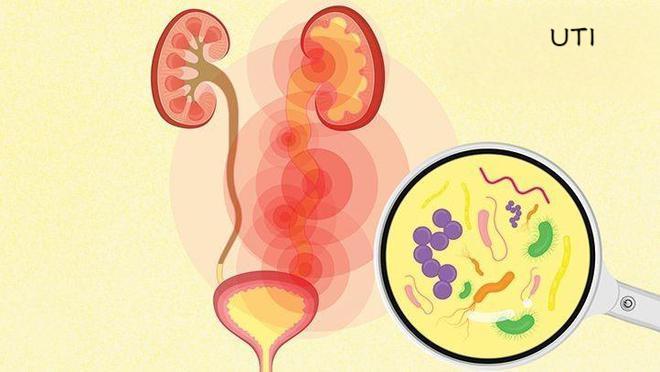

1.1 Prevention of urinary tract infections

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a common disease in adult women, with a prevalence of up to 60%, and are prone to recurrence. The side effects of long-term use of antibiotics and the problem of bacterial resistance caused by repeated treatment have affected the efficacy of treatment.

Ahuja et al. [2] observed under the electron microscope that the number of cilia (i.e., the marginal fringe on the surface of the bacteria that produces adhesins) of Escherichia coli in a medium containing cranberry juice was significantly reduced. Howell et al. [3] isolated 39 uropathogenic E. coli from the urine of patients with UTIs. Urine from healthy women was collected 12 hours before and 12 hours after drinking cranberry juice. The cultured pathogenic bacteria were placed in the collected urine and a cranberry extract solution containing proanthocyanidins, and their adhesion was tested 20 minutes later. Results: Urine before cranberry juice intake had no inhibitory effect on bacterial adhesion; urine after cranberry juice intake inhibited the adhesion of 31 test bacteria (80% of all 39 bacteria) and inhibited the adhesion of 19 antibiotic-resistant bacteria (79% of all 24 antibiotic-resistant bacteria). Moreover, the effect of cranberry juice on inhibiting bacterial adhesion was observed in the urine 2 h after drinking the juice and lasted until 10 h after drinking. The proanthocyanidin solution can inhibit the adhesion of all experimental bacteria at concentrations ranging from 6 to 375 mg/L.

Numerous epidemiological studies have also found that cranberries can prevent UTIs. Foxman et al. [4] found in a case-control study that cranberry juice had a moderate protective effect against UTIs, with an odds ratio of 0·1 (95% confidence interval 0·01 to 0.9). Avorn et al. [5] conducted a randomized controlled trial on 153 elderly female volunteers and found that women who drank 300 ml of cranberry juice daily had a 27% lower risk of recurrent UTIs than the control group (P = 0.06).

Henig et al. [6] provide a detailed account of the clinical trial evidence and biological evidence for cranberry juice in preventing UTIs. More recently, Kontiokari et al. [7] randomly assigned 150 women with UTIs to cranberry juice, a lactic acid drink, or a placebo control group. After six months, the recurrence rates of UTIs in the three groups were 16%, 39%, and 36% respectively (P = 0.023). Stothers et al. [8] divided 150 women aged 21 to 72 years into three groups, which took cranberry tablets, cranberry juice and placebo respectively. After one year, the incidence of at least one UTI in the two experimental groups was 18% and 20%, respectively, which was significantly lower than that in the placebo group (32%).

Regarding the mechanism of cranberry's anti-infection effect, it was once thought that it could acidify urine to inhibit bacteria. It is now generally accepted that the active ingredient proanthocyanidins in cranberries exert an antibacterial effect by inhibiting bacterial adhesion. Proanthocyanidins are a class of highly hydroxylated polyphenolic compounds widely found in plants. Cranberry proanthocyanidin extract has a concentration of 10-50 mg/L and has biological activity that inhibits bacterial adhesion. Other Vaccinium plants also have this activity, but most vegetables and fruits do not. Foo et al. [9] used 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, electron emission mass spectrometry and other methods to detect the structure of proanthocyanidins in cranberries and found that they are different from common proanthocyanidins.

In general plants (such as grapes and cocoa), proanthocyanidins are linked in the B-form, while the proanthocyanidins in cranberries are mainly composed of epicatechin units DP4 and DP5, and at least one A-form link. The most common terminal unit is procyanidin A2, which appears four times more frequently than epicatechin monomers. This A-type connection has a very unique structure and is currently only found in a few plants. This double-ring connection limits rotation around the interflavanone bond and may play a role in inhibiting bacterial adhesion.

However, clinical trials have found that cranberries do not prevent UTIs. McGuinness et al. [10] conducted a randomized controlled trial in multiple sclerosis patients, a population at high risk for UTIs, to observe whether cranberries could prevent UTIs. The results showed that among 153 subjects, oral administration of 8000 mg of cranberry preparations daily did not prevent or delay the onset of UTIs compared with the placebo group. Similar studies by Campbell et al. [11] on prostate cancer patients after radiotherapy and Schlager et al. [12] on children with neurogenic bladder dysfunction (urinary dysfunction caused by damage to the central or peripheral nerves controlling urination, also known as neurogenic bladder, which is a relatively common disease) did not support the preventive effect of cranberries. These negative results may be related to whether the cranberry preparation contains active ingredients.

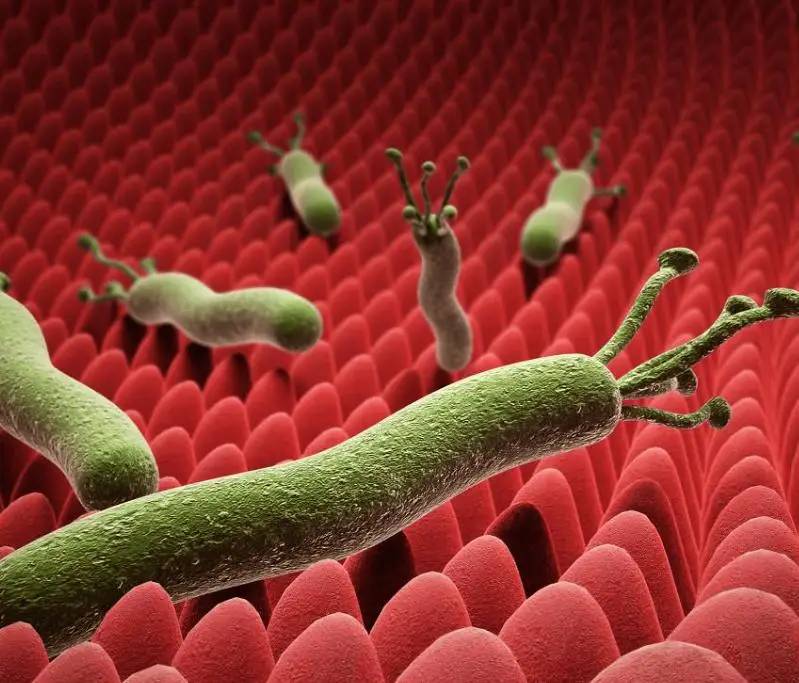

1.2 Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection

Due to its bacteriostatic properties, cranberries are used to eradicate certain bacterial infections, including Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is an important risk factor for gastric cancer, gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers and other diseases. The infection rate of H. pylori varies greatly among different populations, and can be as high as 70% in developing countries.

Shi Tong et al. [13] conducted an animal experiment on the anti-H. pylori infection effect of cranberries. Mice infected with H. pylori were divided into 4 groups and given cranberry juice, triple therapy (amoxicillin + bismuth citrate + metronidazole), cranberry juice plus triple therapy, and phosphate buffer (control), respectively. The mice were killed after 24 hours and 4 weeks of treatment, and H. pylori infection was detected using the rapid urease test and tissue culture. Results: The clearance rates of the test groups after 24 hours were 80%, 100%, and 90%, respectively, which were all significantly higher than those of the control group. The eradication rates of H. pylori in the test groups after 4 weeks were 20%, 80%, and 80%, respectively. This shows that cranberry juice can clear H. pylori in a mouse model, but the effect of eradicating H. pylori is not yet ideal.

The Beijing Cancer Research Institute conducted an intervention trial on the H. pylori-infected population in Linqu, Shandong, a high-incidence area of gastric cancer. 198 H. pylori-positive individuals were randomly divided into two groups, which were given 500 ml of cranberry juice and a placebo, respectively, every day. The H. pylori infection status of the two groups was detected at 35 and 90 days using the 13C-UBT method. The results showed that at 35 days, the H. pylori conversion rate in the cranberry juice group was 14%, and in the control group it was 5% (P<0.05). Since the H. pylori infection rate in the local population is very high (over 70%), taking cranberry juice to prevent H. pylori infection will have a good effect locally. Further research will determine the dose-response relationship of cranberry juice in eliminating H. pylori and prepare for intervention in local children.

1.3 Inhibiting oral bacteria

Cranberries have also been used to remove oral bacteria. Weiss et al. [14] dialyzed cranberry juice with distilled water (retaining components with a molecular weight of 12,000–14,000) to obtain a non-dialysable high-molecular substance (NDM), NDM), and it was found that its concentration of 0∙6g/L-2∙5g/L can reverse the coagulation of different species of bacteria in the mouth, and the concentration of NDM that inhibits bacterial coagulation can be even lower. NDM has the best bacteriostatic effect when one of the bacteria is a Gram-negative anaerobe or both are Gram-negative anaerobes. Saliva has no effect on NDM. In a clinical trial, 45 volunteers were divided into two groups, which used a placebo and an oral rinse with 3.8 g/L NDM, respectively, twice a day for 45 days. The results showed that the total bacterial count in the saliva and the number of Streptococcus mutans in the test group were significantly reduced. A high-molecular substance extracted from other fruits did not have this effect. This high-molecular substance is thermally stable and cannot be digested by insulin. It is estimated that the active ingredient may be proanthocyanidins.

2 Antioxidant and antitumor effects

Most bilberry plants have antioxidant, antitumor, and anti-cardiovascular disease effects. Their ingredients can be roughly divided into: flavonoids, coumarins, phenols, and terpenes. Cranberries have a high content of quercetin (also known as quercetin) among plants of the same species. With the development of testing technology, various components can be further divided into many categories. For example, flavonoids include anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins and flavanones; among these, anthocyanins can reach as many as several dozen types. Kandil et al. [15] fractionated and chromatographed cranberry extracts and found that they contained a series of proanthocyanidins and flavonoids, most of which have antioxidant effects. An ornithine decarboxylase experiment found that a certain extract of cranberries (rich in proanthocyanidins) also has a chemical effect in preventing tumors. Further analysis of its components includes: seven flavonoids, mainly pentahydroxyflavone and myricetin, and their corresponding glycosides, epicatechin, catechin, gallocatechin dimer and epigallocatechin, as well as a series of oligomeric proanthocyanidins.

2.1 Antioxidant effect

Reed et al. [16] found that the flavonoids in cranberries have antioxidant properties in both in vivo and in vitro experiments, and that flavonols and proanthocyanidins in particular have a preventive effect against atherosclerosis. These compounds can inhibit low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation as well as platelet aggregation and adhesion, inhibit enzymes in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism; regulate the immune response to LDL oxidation, increase reverse cholesterol transport, and lower total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol.

Youdim et al. [17] reported that the anthocyanins and hydroxycinnamic acids in cranberry extract can protect cardiovascular endothelial cells. These two substances can enter endothelial cells and improve the cells' resistance to oxidation at the plasma membrane and cytoplasmic levels, resisting the damage caused by hydrogen peroxide and the damage caused by the upregulation of tumor necrosis factor (TNFα), which results in an increase in various inflammatory factors (such as interleukin-8).

2.2 Antitumor effect

Sun et al. [18] used HepG2 cells to test the antiproliferative activity of 19 fruit extracts in vitro and found that cranberry had the strongest effect in inhibiting cell proliferation, with an effective dose of 14.5 g/L ± 0.5 g/L (EC50). The antioxidant activity was tested using the total oxygen radical scavenging capacity (TOSC) assay, and cranberry was still the most active. In addition, they improved the measurement method to measure the phenol content in fruits, including both free and bound forms, and the results showed that cranberries had the highest phenol content among 19 fruits.

Murphy et al. [19] reported that triterpenoid esters in cranberries have the effect of inhibiting tumor cell growth. Fractionation and chromatography techniques, as well as purity identification by HPLC and analysis by nuclear magnetic resonance, revealed that these compounds contained cis- and trans-ursonic acid (urson). Purified triterpenic cinnamic acid showed high antitumor activity in inhibition experiments with several tumor cell lines (breast cancer, cervical cancer, prostate cancer), while anthocyanin-3-galactoside was much less cytotoxic. Phenolic acids have almost no anti-tumor activity. Roy [20] found that the flavonoids in cranberries can inhibit H2O2 and TNFα-induced expression of vascular growth factor (VEGF) and inhibit angiogenesis. In addition, cranberry peel contains a lot of resveratrol [21], which can inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth in vitro.

In short, cranberries are a natural berry that, according to foreign literature, has no serious adverse reactions when taken long-term. Cranberry consumption not only prevents bacterial infections, but also has antioxidant and anti-tumor properties, making it especially suitable for the elderly, especially elderly women. Cranberry health food is already on the market in China. Cranberries have great potential for health development and deserve further research.

Reference:

[1]Gunther S ,et al.[J].J Am Diet Assoc ,2004,104(1):27-34.

[2]Ahuja S ,et al.[J].J Urol ,1998,159:559-562.

[3]Howell AB , et al.[ J ]. JAMA , 2002, 287(23):3082-3083.

[4]Foxman B ,et al.[J].J Clin Epidemiol ,2001,54(7):710-718.

[5]Avorn J ,et al.[J].JAMA ,1994,271(10):751-754.

[6]Henig YS ,et al.[J].Nutrition ,2000,16(7-8):684-687.

[7]Kontiokari T , et al.[ J ]. BMJ , 2001, 322(7302):1571-1573.

[8]Stothers L .[J].Can J Urol ,2002,9(3):1558-1562.

[9]Foo LY ,et al.[J].Phytochemistry ,2000,54(2):173-181.

[10]McGuinness SD ,et al.[J].J Neurosci Nurs ,2002,34(1):4-7.

[11]Campbell G ,et al .[J].Clin Oncol ,2003,15(6):322-328.

[12]Schlager TA ,et al.[J].J Pediatr ,1999,135(6):664-666.

[13] Shi Tong, et al. [J]. Gastroenterology, 2003, 8(5): 265-268.

[14]Weiss EL ,et al .[J].Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr ,2002,42(3Suppl):285-292.

[15]Kandil FE ,et al.[J ].J Agric Food Chem ,2002,50(5):1063-1069.

[16]Reed J .[J].Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr ,2002,42(3Suppl):301-316.

[17]Youdim KA ,et al.[J].J Nutr Biochem ,2002,13(5):282-288.

[18]Sun J ,et al.[J].J Agric Food Chem ,2002,50(25):7449-7454.

[19]Murphy BT ,et al.[J].J Agric Food Chem ,2003,51(12):3541-3545.

[20]Roy S ,et al.[J].Free Radic Res ,2002,36(9):1023-1031.

[21]Wang Y ,et al.[J].J Agric Food Chem ,2002,50(3):431-435.

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese