How to Extract Natural Colour?

Numerous biological, nutritional and medical research reports have pointed out that Natural Colour has nutritional and physiological health functions, while synthetic pigments can adversely affect human health. With the continuous improvement of people's living standards and the continuous development of the food industry, safe and green Natural Colour is becoming more and more popular and sought after. There are three main ways to produce and obtain pigments: direct extraction, artificial synthesis, and production using biotechnology [1]. Natural colours are unstable, and in order to maintain their physiological activity, the extraction of natural colours should generally use milder process conditions. With the rapid development of science and technology, the extraction process of natural colours is also rapidly updating, showing a development direction that is supplemented by common extraction methods and dominated by high-tech extraction technologies that are energy-saving, efficient and environmentally friendly.

1 Traditional extraction methods

1.1 Solvent extraction

The common solvent extraction method is based on the different properties of the target pigment and impurities (mainly differences in solubility and polarity), using the principle of like dissolves like to select different solvents (commonly used extraction agents include water, acid-base solutions, organic solvents such as ethanol and acetone), to achieve the purpose of separating the pigment. The main extraction methods are maceration, percolation, reflux, and continuous reflux. The main process is: screening materials – soaking – filtering – concentrating and drying – finished product. Korea Ting et al. [2] used ethyl acetate to extract lycopene from tomatoes. The optimal process liquid ratio was 4:1 (mL/g), the time was 50 min, the temperature was 45 °C, the number of times was 3, and the lycopene extraction rate was above 85%.

Yao Yurong et al. [3] used formic acid as an extractant to extract anthocyanins from purple sweet potatoes. The anthocyanin yield after three extractions was up to 95.6%. Chen Tingchun et al. [4] extracted natural white cottonseed shell pigments with a 1% NaOH solution by mass, and discussed the effects of light, temperature, water quality, and pH on the stability of the pigments. It was found that the pigment had a strong absorption peak at 210 nm, and the pigment was stable to oxidants, light, and temperatures below 100 °C. This extraction method is also often used in combination with other methods to improve the yield and quality of the product. For example, Sun Peidong et al. [5] used high pressure to pretreat tomatoes, and then extracted lycopene with ethyl acetate as the solvent. The result was that the extraction rate was 4.8 times that of the untreated sample.

1.2 Direct pulverization method

This method is not commonly used, and the product is obtained mainly by drying and pulverizing the material. The process flow is: raw material – screening – washing – drying – pulverizing – pigment product [6]. This process can be used to prepare cocoa bean pigments, lycopene, etc., but the product obtained is relatively crude.

1.3 Enzyme extraction method

Plant pigments are mainly found inside the cells and are surrounded by the cell wall, which is mainly composed of cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin. The poor permeability of the cell wall prevents the pigments from dissolving and reduces the extraction rate. The cell walls are hydrolyzed using enzymes, mainly cellulase and pectinase, which cause the cell walls to expand, rupture, and loosen, thereby facilitating the diffusion of pigments into the extracellular space and the diffusion and penetration of solvents into the cell, thus increasing the solubility of pigments and improving the pigment extraction rate. For example, Li Mengqing et al. [7] used cellulase to act on grape cob meal, which increased the extraction rate of proanthocyanidins by nearly 4 times. Chen He et al. [8] analyzed the effects of factors such as temperature, reaction time, pH, and hemicellulase dosage on the extraction of turmeric pigments through single factor and orthogonal experiments, and obtained the optimal extraction process: enzyme dosage 7.0 mg/g, pH 4.3, time 4.0 h, temperature 45 °C, compared with the common solvent extraction method, the pigment extraction rate was greatly improved.

Zhao Yuhong et al. [9] used cellulase and pectinase to simultaneously hydrolyze the residue of blueberry to extract anthocyanins. The optimal process parameters were determined by single factor and orthogonal experiments. The results showed that the use of double enzyme complex hydrolysis can significantly improve the anthocyanin extraction rate compared with single enzyme hydrolysis. In order to improve the pigment extraction rate, the enzyme method can also be combined with other techniques. For example, the combination of cellulase and ultrasonic waves can be used to extract the pigment from hazelnut shells. The results show that the combination of the two can effectively improve the pigment extraction rate (the absorbance increases by about 20%), and can also reduce the amount of enzyme used, saving costs [10].

2 New extraction techniques

2.1 Supercritical fluid extraction

Supercritical fluid refers to a gas, liquid or gas-liquid mixture. However, under a certain temperature and pressure, the phenomenon of the disappearance of the gas-liquid interface will occur, and the fluid will be in a supercritical state that is different from the liquid, gas and solid states, and has some special physical and chemical properties of both liquids and gases (density and solubility close to liquids, viscosity and diffusion properties close to gases) [11]. Common supercritical fluids include carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, ethane, ethylene, propane, methanol, ethanol, benzene, toluene, ammonia, water, etc.; the most commonly used is carbon dioxide (critical conditions close to room temperature, non-toxic and tasteless, chemically stable, inexpensive and readily available). Supercritical fluid extraction technology is an emerging extraction and separation technology that uses supercritical fluids as extraction agents to extract and separate target substances.

For example, Zheng Hongyan et al. [12] studied the process conditions for the extraction of zeaxanthin from corn using supercritical CO2 at 23 MPa, 40 °C, and 30% anhydrous ethanol as the extractant. The extraction rate was 2.2% higher than that of the solvent extraction method under the condition of an extraction time of 3 h. The extraction rate of dried microalgal chlorophyll using supercritical CO2 fluid at 40 MPa and 60 °C can reach 0.2238% [13]. The concentration of astaxanthin extracted from shrimp shells using supercritical CO2 fluid can reach 8.331% [14]. With the continuous development of science and technology, supercritical fluid extraction has been developed to be used in conjunction with other high-tech methods, such as molecular distillation, chromatography, nuclear magnetic resonance, adsorption separation, ultrafiltration, and other techniques, to achieve complementary advantages and broaden the scope of applications.

2.2 Ultrasonic-assisted extraction

The principle of ultrasonic extraction is to use the special effects of ultrasonic waves, such as the strong cavitation effect, interfacial effect, energy concentration effect and high acceleration, as well as the resulting multi-stage effects such as oscillation, crushing, diffusion and collapse, to destroy cells, thereby accelerating the diffusion and penetration of the extraction agent into the cells, and also accelerating the dissolution of the extracted substance in the extraction agent, and improving the extraction rate and purity of the pigment [15]. The main factors affecting this process are: solvent type and concentration, liquid-to-material ratio, ultrasonic power and frequency, processing time and temperature. Wang He-cai [16] used ultrasound to extract purple sweet potato pigment. The results showed that the effect of extracting purple sweet potato pigment under the action of ultrasound was better than that of the conventional method under the same conditions. The extraction efficiency was about 1.3 times that of the conventional extraction, and the optimal process was: distilled water with a pH of 1.0 as the extracting agent, ultrasonic 250W, liquid-to-material ratio 3:300, extraction at 70°C for 35 min. Liu Pinghuai et al. [17] used ultrasonic recycling technology to extract pigments from discarded pineapple peels, and obtained pigments with a high color value (four times that of the pineapple flesh pigment) and an optimal extraction process. The extraction rate was greatly increased, which also provides a reference for the deep processing of pineapple peels.

2.3 Microwave-assisted extraction method

Microwave extraction is a novel separation and extraction technique that combines microwaves, which can selectively heat, with solvent extraction technology. It makes use of the difference in microwave absorption capacity in the microwave field to selectively heat certain regions or components in the extraction system, thereby dissolving the target components from the raw material and transferring them to an extractant with a smaller dielectric constant and relatively weak microwave absorption capacity, so as to achieve the goal of rapid short-term extraction [18-19]. Chen He et al. [20] used microwave technology to assist in the extraction of turmeric pigment, and obtained the optimal process through an orthogonal experiment: 60% ethanol as the extracting agent, microwave power 450W, extraction time 180s, and material-to-liquid ratio 1:35. Compared with the traditional solvent extraction method, the pigment yield increased by 80.3%. Jia Yanju et al. [21] studied the effects of microwave power and irradiation time on the extraction of fish scale pigment. The analysis of variance showed that the effects of the two were significant, and the optimal power and irradiation time were 640 W and 150 s, respectively. However, compared with the shaking extraction method, the extraction effect of fish scale pigment was poor, which may be due to the influence of the fish scale tissue structure.

2.4 Resin adsorption method

Adsorption resin is a kind of porous, highly cross-linked polymer adsorbent with a large specific surface area (mainly the surface area inside the pores). According to the principles of surface chemistry, the surface has adsorption capacity, so it can adsorb certain substances from the gas or liquid phase. Adsorption resins mainly use van der Waals forces, dipole-dipole interactions and hydrogen bonding to adsorb substances. The adsorption is selective depending on the surface properties and the surface force field. This method mainly uses the different properties (mainly polarity) of the components in the mixture to select the appropriate adsorption resin and eluent, and selectively separates and purifies the substances by adsorption and desorption. According to their polarity, adsorption resins can be divided into four categories: non-polar adsorption resins, medium-polar adsorption resins, polar adsorption resins and strong-polar adsorption resins. Non-polar resins are often used to adsorb non-polar substances from polar substances, while polar resins are suitable for adsorbing polar substances from non-polar substances.

Chen Zhiqiang et al. [22] studied the adsorption of astaxanthin by seven different macroporous resins and screened AB-8 macroporous resin as the one with better adsorption. The adsorption capacity of astaxanthin was about 24.17 mg/g, the desorption rate was 95.2%, and the maximum sample amount (1 g of dry resin) was 23.0 mg of astaxanthin. and it was determined that 8 times the volume of the bed of the column of ethyl acetate was used as the eluent, and the purity of the purified astaxanthin was 14.73%. Ding Jie [23] used orthogonal experiments, adsorption capacity and desorption rate indicators to analyze the main influencing factors in the adsorption and separation of mulberry red pigment by AB-8 type macroporous resin. The results showed that the elution effect was best when 80% ethanol (pH 2.0) was used as the eluent at a dosage of 2BV and an elution rate of 1BV/h. It was also found that the pigment had good stability under acidic conditions and at a temperature of 60°C, but was easily decomposed under alkaline conditions and in the presence of light.

2.5 Membrane separation

Membrane separation technology is a new energy-saving technology developed in the 1970s that does not involve phase changes. It uses the difference in the selective permeation properties of natural or synthetic polymer membranes for the components in a mixture to achieve the separation, purification and concentration of substances with the help of chemical potential differences or the driving force of external energy. The driving forces include concentration differences, pressure differences, and potential differences. The mechanisms involved include mechanical filtration, dissolution-diffusion, and mass transfer [24]. It is mainly based on the differences in molecular weight, particle size, and shape between the components to separate them. According to the molecular size of the substance to be separated, membrane separation can be divided into microfiltration, dialysis, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, reverse osmosis, electrodialysis, liquid membrane separation, etc.

Li Yuanyuan et al. [25] used ceramic membrane microfiltration to extract and purify gardenia yellow pigment, and studied the effects of different membrane pore sizes and operating pressures on the quality of the pigment. The results showed that the quality of the gardenia yellow pigment obtained by microfiltration was higher when the pore size was 200 nm and the operating pressure was 0.125 MPa. The gardenia yellow extract was then subjected to nanofiltration using a polyamide membrane, the filtrate can be concentrated more than three times. The membrane surface flow rate and membrane filtration flux have a significant effect on pigment separation. Guo Hong et al. [26] used ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis technology to purify and concentrate the pigments of roselle and purple back-daylily, respectively, and studied the effects of extraction temperature, time, frequency, material ratio, and raw material quality on the pigment extraction rate. The results showed that ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis technology can reduce the loss of pigments during purification and concentration.

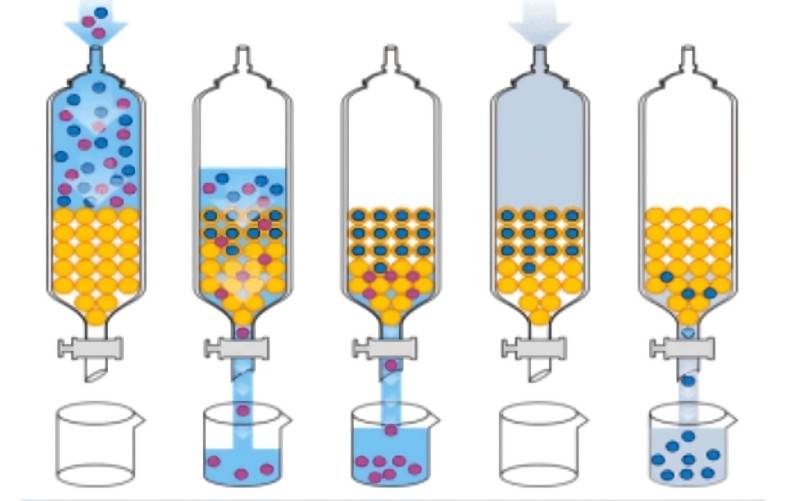

2.6 Gel chromatography separation method

The gel beads used in gel chromatography have a porous, highly cross-linked network structure, and the degree of cross-linking or pore size of the gel beads determines the relative molecular mass range of the mixture that can be separated by the gel. The principle is the molecular sieve effect, which uses the difference in molecular size to separate and purify substances. Commonly used gels include: dextran gel (Sephadex), polyacrylamide gel (Bio-gel P), and agarose gel (Sepharose or Bio-gel A). Due to the differences in molecular weight, size and shape of the various substances in the mixture, when the mixture is eluted through the column, the large molecules cannot enter the interior of the gel beads because their diameter is larger than the pores of the gel, and are excluded from the gaps between the gel particles.

They move downward with the eluent, so the process is short, the flow rate is fast, and they flow out of the column first; while the small molecules have a diameter smaller than the pores of the gel, can move freely in and out of the gel pores, so the process is long and the movement speed is slow, and finally it flows out of the column. In this way, molecules of different sizes are separated due to their different paths, and macromolecular substances are eluted first, followed by small molecules. Lv Xiaoling et al. [27] analyzed the influencing factors in the process of refining gardenia yellow pigment by gel chromatography through single-factor experiments. The research shows that under the optimal process conditions: glucan gel as a support, a single column 30 cm high, 2 cm in diameter, 1.8 mL sample size, distilled water as the eluent, double column tandem elution, flow rate 4 mL/min, pigment yield up to 48.9%.

2.7 Molecular distillation separation method

Molecular distillation separation technology is a special and advanced liquid-liquid separation technology developed in the 1930s. It is a kind of non-equilibrium distillation, also known as short-path distillation. It is a non-equilibrium distillation, also known as short-path distillation, which is carried out at a certain temperature (much lower than the normal boiling point) and pressure (0.133 to 1 MPa). The components to be separated are heated and evaporated, overflowing the liquid surface. The substances are then separated and purified due to the different mean free paths of molecular motion of different substances. The free path of molecular motion refers to the distance a molecule travels between collisions with neighboring molecules.

The average free path of molecular motion of a specific molecule over a certain period of time is called the average free path of molecular motion. After the system to be separated is heated to gain sufficient energy, the molecules overflow the surface of the liquid. The mean free path of light molecules is large, while that of heavy molecules is small. A condensing plate is placed on the surface of the liquid (between the mean free paths of light and heavy molecules). Light molecules can reach the condensing plate and condense and move out, while heavy molecules cannot reach the condensing plate and return to the gas-liquid system [28-29]. Zhong Geng [30] and others used molecular distillation technology to extract carotenoids with high chroma and no organic solvents from dewaxed sweet orange oil. Batistella [31] and others used molecular distillation technology to separate carotenoids and biodiesel from palm oil, the yield of carotenoids was as high as 3000mg/kg. Using molecular distillation technology to refine the crude paprika red pigment obtained by solvent extraction not only has the effect of removing pungency, odor and solvent, but also improves product quality and greatly reduces production costs [32].

3 Outlook

With the rising call for “returning to nature and pursuing green safety,” the development and utilization of natural colors has also developed rapidly (growing at a rate of 4% to more than 10% per year). However, the research and development of natural colors still faces many problems: the extraction rate of natural colors is low and the cost is high; the stability of pigments is poor, and they are sensitive to external conditions such as light and heat; there are many types, and research and development dispersed, lacking unified management and toxicological evaluation.

The future research and development direction of Natural Colour is to use biotechnology such as cell engineering, genetic engineering, fermentation engineering, enzyme engineering, and microbial engineering to solve the problem of raw material supply; use microencapsulation technology, pigment molecular structure modification technology, and production compounding technology to improve the stability of Natural Colour and enhance its natural coloring power; and use supercritical fluid extraction, gel chromatography, affinity chromatography, molecular distillation, reverse gel extraction, two-phase extraction, liquid membrane separation and other high-tech methods, as well as the combination of various high-tech methods, to improve the yield of Natural Colour, improve product quality and reduce production costs. With the research goals of developing new functional pigments, seeking new sources of raw materials, improving pigment stability and increasing pigment extraction rates, the development and application of Natural Colour will have even broader prospects.

References

[1] Deng Xiangyuan, Wang Shujun, Li Fuchao, et al. Resources and applications of natural color [J]. Chinese condiments, 2006 (10): 49-53.

[2] Han Guoting. Research on the extraction process conditions of lycopene [J]. Anhui Agricultural Science and Technology, 2008, 36 (30): 1298-1299.

[3] Yao Yurong, Mu Taihua, Zhang Wei. Extraction, purification and stability of anthocyanins from purple sweet potato [J]. Food Science and Technology, 2009, 34 (6): 195-199.

[4] Chen T C, Zhao Z, Zhu Q, et al. Extraction and properties of natural white cottonseed shell pigments [J]. Dyes and Pigments, 2010, 47(1): 31-35.

[5] Sun P D, Liu Y Q, Sun Y D. Extraction of Natural Colour by high pressure method [J]. China Food Additives, 2005(5): 111-112.

[6] Chen Ming, Li Yan. Development and utilization of natural plant food coloring [J]. Chinese Wild Plant Resources, 2000, 19 (4): 23-26.

[7] Li Mengqing, Zhang Jie, Nie Yuan, et al. Study on the enzymatic extraction of proanthocyanidins and resveratrol from grape stems [J]. Natural Product Research and Development, 2009, 21 (20): 291-295.

[8] Chen He, Li Shiyu, Shu Guowei, et al. Study on the extraction of turmeric pigment assisted by hemicellulose [J]. Chinese Condiments, 2010, 35 (2): 106-108.

[9] Zhao Y H, Miao Y, Zhang L G. Study on the enzymatic hydrolysis conditions of anthocyanins from the pomace of blueberry by double enzyme method [J]. Chinese Journal of Food Science, 2008, 8 (4): 75-79.

[10] Zhao Y H, Wang J, Jin X M. Study on the process conditions of ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic extraction of hazelnut shell pigments [J]. Chinese Condiments, 2010, 35(4): 110-114.

[11] Hawthorne S B, Miller D J. Direct comparison of soxhlet and low-and high-temperature supercritical CO2 extraction efficiencies of organics from environmental solids [J]. Anal Chem, 1994, 66(22): 4005-4012.

[12]Zheng Hongyan, Chang Youquan. Study on supercritical CO2 extraction of zeaxanthin from corn [J]. Food and Machinery, 2004, 20(6): 25-27.

[13] M-Sanchez M D. Supercritical fluid extraction of carotenoids and chloro- phylla from Nannochloropsis gaditana [J]. Journal of Food Engineering, 2005 (66): 245-251

[14] Tsuneo, Yoko, Koichi, et al. Extraction of dye from krill [P]. JP: 04057853A2, 1992-02-05.

[15] Sinisterra J V. Application of ultrasound to biotechnology: an overview [J]. Ultrasonics, 1992, 30(3): 180-185.

[16] Wang H C, Cai J, Hu Q H, et al. Study on the process of purple sweet potato pigment extraction assisted by ultrasound [J]. Jiangsu Agricultural Science, 2009(2): 236-238.

[17] Liu Pinghuai, Liu Yangyang, Shi Jie, et al. Ultrasonic extraction of pigments from discarded pineapple peels and their anti-allergic activity [J]. Fine Chemicals, 2010, 27 (2): 165-169.

[18]Cheez K, Kwong M K, Lee H K. Microwave-assisted solvent elution technique for the extraction of organic pollutants in water[J]. Anal Chem, 1996, 330: 217.

[19] Camel V. Recent extraction techniques for solids matrices supercritical fluid extraction, pressurized fluid extraction and microwave-assisted extraction: Their potential and pitfalls [J]. Analyst, 2001, 126: 1097-1104.

[20]Chen He, Li Shiyu, Shu Guowei, et al. Study on the extraction of turmeric pigment assisted by microwave[J]. Food Industry Science and Technology, 2010, 31 (3): 285-287.

[21]Jia Yanju, Zhang Can. Study on the extraction of fish scale pigment by microwave method[J]. Anhui Agricultural Science, 2010, 38 (8): 3900-3901

[22] Chen Zhiqiang, Jin Yang, Ren Lu. Separation and purification of astaxanthin by macroporous resin in non-aqueous media [J]. Bioprocess Engineering, 2009, 7(3): 39-42.

[23] Ding J. Separation and purification of mulberry red pigment by AB-8 macroporous resin [J]. Anhui Agricultural Science Bulletin, 2009, 15(15): 216-218.

[24] Xu Y. Polymer Membrane Materials [M]. Beijing: Chemical Industry Press, 2005.

[25] Li Yuanyuan, Gao Yanxiang. Study on the purification of gardenia yellow pigment by membrane separation technology [J]. Food Science, 2006, 27 (6): 113-117.

[26] Guo Hong. Study on the purification and concentration of edible natural color by membrane separation technology [C]. Beijing Food Science Society Youth Science and Technology Paper Collection, 1992: 45-65.

[27] Lv Xiaoling, Yao Zhongming, Jiang Pingping. Study on the purification of gardenia yellow pigment by gel chromatography [J]. Food and Fermentation Industry, 2001, 27 (4): 39-42.

[28]Fischer W, Bethge D. Short path distillation[J]. Distillation Absorption, 1992, 128: 403-414.

[29] Batistella C B, Wolf Maciel M R. Recovery of carotenoids from palm oil by molecular distillation [J]. Computer Chem. Engng, 1998 (22): 53-60.

[30] Zhong G, Wu Y X, Zeng E K. A new process for the extraction of natural carotenoids [J]. Sichuan Daily Chemical, 1995 (3): 6-9.

[31]Batistella C B , Morase E B , Maciel F R , et al. Molecular distillation process for recovering and carotenoids form palm oil [J]. Applied Biochemistry Biotechnology, 2002 (98): 1149-1159.

[32] Shan Fang, Tian Zhifang, Bian Junsheng, et al. Application of molecular distillation technology in the refining process of paprika red [J]. Chinese Journal of Food Science, 2003 (supplement): 144-147.

English

English French

French Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Korean

Korean Japanese

Japanese